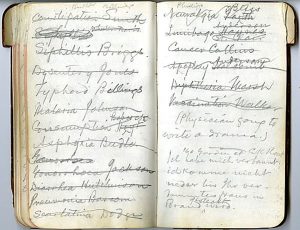

Thomas Hardy typically had several notebooks on the go, each one carefully labelled Poetical Matter; Literary Notebook; Studies, Specimens, etc; or Facts. In Facts, Hardy and his first wife, Emma, recorded curious incidents culled from local newspapers. One three-line entry is titled “Sale of Wife”—a note that grew into The Mayor of Casterbridge.

Writers are inveterate notebook-fillers. They not only keep notebooks, they talk about them—about their dream of the ideal notebook and their frustration with the reality of trying to trap on paper their inspirations and observations.

A Different Breed Altogether

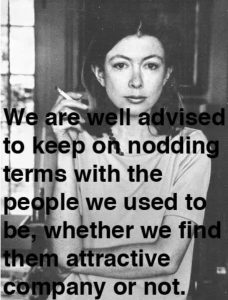

According to Joan Didion, “Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.”

According to Joan Didion, “Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.”

She asked only one thing of her notebooks—that they help her “remember what it is to be me. As she wrote in her essay “On Keeping a Notebook” in Slouching Toward Bethlehem, “I have already lost touch with a couple of people I used to be.”

Virginia Woolf mused more gently, “What sort of diary should I like mine to be? Something loose knit and yet not slovenly, so elastic that it will embrace anything, solemn, slight, or beautiful, that comes to mind.”

Writers spend their days filling manuscript pages with words, but a notebook offers a different kind of tabula rasa—intimate, unconditionally accepting, welcoming of the kind of thoughts one can admit only to oneself.

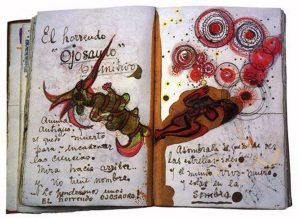

It was this promise of a private, personal space that drew Anaïs Nin to her notebook: “Writing for a hostile world discouraged me; writing for the diary gave me the illusion of a warm ambiance I needed to flower in.”

Life Drawing

I bristle at the word “diary,” redolent of ten-year-olds hiding pastel, padlocked books under mattresses. “Journal” sounds too severely disciplined, a place where a parson or scientist might record the weather or the action of one’s bowels.

Notebook is refreshingly plainspoken: a book for notes. According to Mirriam-Webster, to note is to observe with care; to remark upon; to record and preserve. The word has hardly changed since the Romans coined “nota” to indicate a mark or sign.

John Irving eschewed diaries, too, but he took up the notebook habit early. “I never wrote about my day and what happened to me, but I described things—almost like landscape drawing, or life drawing.”

A Junkyard of the Mind

Not all writers keep notebooks. Zadie Smith admits she’s tried—“it seems like a very writerly thing to do, but my mind doesn’t work that way. I tend to get the idea for a novel in a big splash.”

For many writers, though, a notebook is an antidote to the unreliability of the mind. As Jack London put it, “Cheap paper is less perishable than gray matter. And lead pencil markings endure longer than memory.”

Indeed, Scottish children’s writer Nicola Davies calls her notebook “a cross between an external hard drive for my brain, the place I put anything I need to remember for my writing, and a camera, where I can take snapshots in words of what I see and hear. “

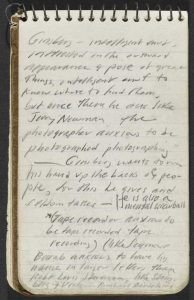

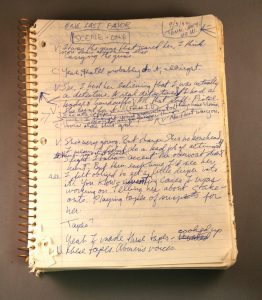

Sam Shepard’s notebooks are like that, a collage of random tidbits: lists of tree species, guitar chords for Mexican songs, sketches for stage sets and vegetable gardens, quotations that might be overheard conversation or dialogue crafted from his imagination, it’s impossible to tell. Review clippings and articles of interest to Shepard as a writer, rancher, actor, and musician are stuffed between the covers; taped inside the red-earth cover of one is a business card for a farrier in La Cienega.

Mario Vargas Llosa’s notebooks are lean rather than protean, their pages devoted exclusively to early drafts of his books. He is always writing: in airports between events, in restaurants between courses. “It’s very important not to abandon the things I’m working on,” he told the Mexican magazine, Gatopardo, on the release of his autobiography The Call of the Tribe this spring. “If I stop writing for too long, I have a terrible time starting up again.”

When he’s home, Llosa writes in his notebook in the mornings and in the afternoons he transcribes the passages into the computer. “For me, a narrative’s rhythm is like that of handwriting,” he explains. “These aren’t notes. They’re manuscripts.”

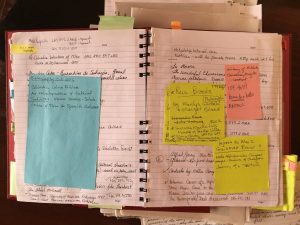

I’m envious of writers like Llosa who seem able to separate art and life. My notebooks are more Shepardian—an impossible tangle of ideas, observation, riffs of literary experimentation, and what I need to buy for dinner.

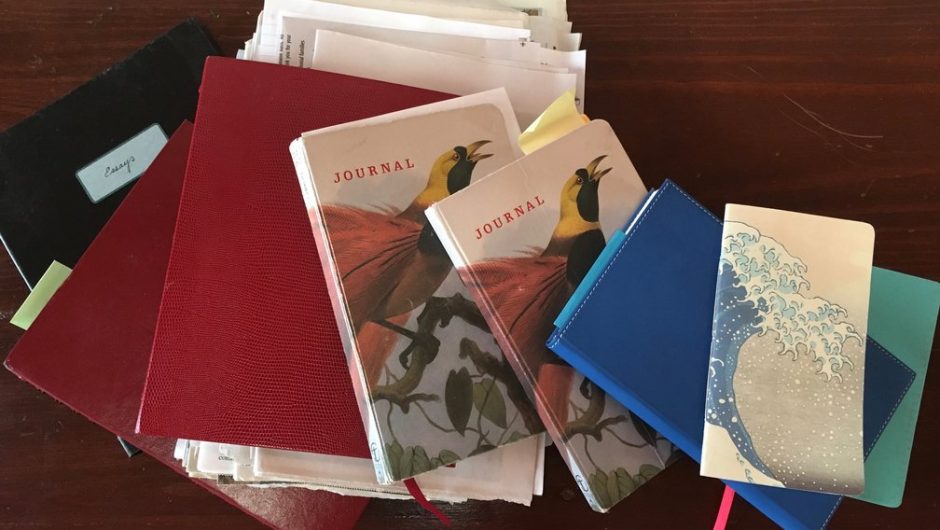

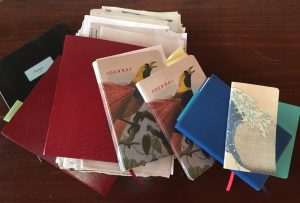

They don’t start out like that. At the beginning of each project, I carefully choose a fresh notebook. Since I often have two or three projects developing at once, I might have three sets of project notebooks, plus a notebook for ideas, and one where I record my thoughts on the books I’m reading. My favorite size—5×9, perfect bound, hardcover—is too big to carry around, so I also keep a small notebook in my pocket or purse for gathering fleeting gestures, snatches of dialogue, passing ideas.

At the moment, I am running eight notebooks. I’m careful to choose covers that are visually distinct, but even so, I never seem able to lay my hand on the right notebook at the right moment. And despite my best intentions, I almost never transcribe the bits from my carry-around book into their proper place. My careful organization soon devolves from systematic to slovenly.

This jumbled kind of writer’s notebook might seem like a junkyard of the mind, a repository of failed attempts, false starts, and lost opportunities. But writers are a curiously optimistic lot. Or at least I am. I see my notebooks instead as treasure chests stuffed with diamonds-in-the-rough. Like an obsessive rock collector, I keep everything, hoping that amidst the rubble I’ve kept a gem.

Cover Stories

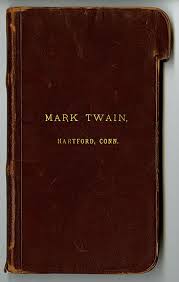

My husband always buys black notebooks of a certain size. In this he is akin to Mark Twain, who designed his own notebook and had them custom-made with a tab on each page. When a page was full, Twain would tear off the tab, so he could see at a glance where the next blank page began.

At the other end of the OCD scale, Jean-Jacques Rousseau made notes on playing cards as he walked, observations that became Reveries of a Solitary Walker.

I am somewhere between. I have notebooks, dozens of them filled over the years, but they are a riot of colour, size, shape, and texture, as if I shop in the marked-down bins at the Dollar Store (which I do). The spines bulge with the notes I’ve made on restaurant receipts, envelopes, Post-its, junk mail, whatever is at hand.

I long to be consistent. To be like the South African writer Damon Galgut, who writes with a fountain pen in bound notebooks he buys in India. I dream of a row of identical spines neatly scribed with the project and year. But I’m not like that. And the truth is, I’ve grown fond of my motley miscellanies, where the workings of my mind and heart are displayed less like a library than a sprawling garage sale.

You Can’t Lie to Me

“If you want to write,” Madeleine L’Engle said, “you need to keep an honest, unperishable journal that nobody reads, nobody but you.”

Yet writers’ notebooks regularly find their way into public archives, where they are available to be read by anyone willing to don a pair of white cotton gloves. Recently, the British Library put a stack of writers’ personal archives online, rendering obsolete even the gloves and the hushed reverence of a reading room.

My husband and I donate our literary papers to Queen’s University Archives, but we haven’t yet given up our notebooks, which line several shelves in our studies. (We have as many empty notebooks as full ones; we need never buy another, not as long as we live, although of course we will.)

My husband consults his notebooks often. I almost never read mine. The action of writing, I tell myself, is enough to etch a note into my brain.

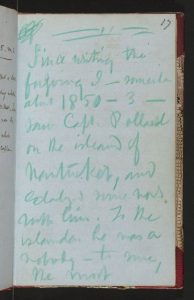

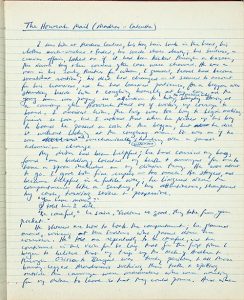

Recently, though, I went back through my notebooks to determine when, in fact, I started work on my about-to-be-published novel. I found it unfathomable that I had been thinking about and writing this book for 14 years, but there, in the fall of 2004, was the first sentence of Refuge: “You can’t lie to me.”

I was astonished. I got out the finished manuscript and read it side by side with the scrawled lines in the old green notebook. The two were almost identical, right down to the last line of the first page: “The only one who can lie to me is me.”

Calligraphic Marvels

Will the next generation of writers have notebooks to consult? Will archives have notebooks to collect?

Paul Theroux worries about the loss of this paper memory: “No more a great stack of manuscripts, letters, and notebooks from a writer’s life, but only a tiny pile of disks, little plastic cookies where once were calligraphic marvels.”

I admit that increasingly over the past few years, instead of writing in my notebook, I’ve been sending myself emails of ideas, phrases, snippet of scenes. At first I transcribed these into notebooks but lately, I bump them into a computer file that I’m fairly sure I’ll never print. No one will ever read my book-fodder but me. And maybe that’s just fine.

4 Comments

This post is so reassuring! I often berate myself for not being more systematic, more organized. I have several notebooks on the go right now, none of them as colorful as yours, but dear to me nonetheless.

I am very fond of Levenger Circa notebooks because I can shift pages around. I am lately seriously addicted to “Semikolon Mucho” A5 spiral notebooks because ink doesn’t bleed through onto the next page.

I no longer have any patience with notebooks that aren’t spiral-bound, frankly; I like to fold them over as I write.

I’ve been a collector of notebooks for decades. I love to find eccentric notebooks in my travels and seeing them all lined up on a shelf back home I especially like that there isn’t anything written in them. There is something so hopeful about that.

Stationery-addiction is the best!

I, too, love notebooks. I have an entire shelf of them in my office, all devoted to my scribblings when I travel: where I stayed and what the weather was like, but also lists of what gifts I have bought for people so I don’t inadvertently buy someone the same gift twice and, most important, my local market food lists. I jam memorabilia from every trip into those books. And, I actually go back through them to refresh my memory, to plan for future trips and to help friends who are heading to the same destination.

As important as the notebooks — and I can spend a ridiculous amount of time in a stationery store trying to choose the perfect one — is the right pen.A rich royal blue, fine point that does not bleed through the page is always my first choice.

Wonderful post, and I appreciated the visuals as well. Reading Elizabeth Gilbert’s book BIG MAGIC, to be discussed tonight at book club, I came across a short quote I was inclined to share. Gilbert lists the many jobs she held in her twenties, including waitressing at a diner and later bartending, which helped in her “deliberate search for material.”

“Working at the diner was great,” she writes, “because I had access to dozens of different voices a day. I kept two notebooks in my back pockets — one for my customers’ orders, and the other for my customers’ dialogue. Working at the bar was even better, because those characters were often tipsy and thus were even more forthcoming in their narratives.”

For me, cellphone conversations overheard on the street, on a bus, or in a coffee shop, although one-sided, provide much fodder for creative speculation 🙂

I can never resist buying a new notebook, even when I’m only part-way through the last one. It takes me two years to fill a notebook; in order to fill all the empty notebooks I have in reserve, I will have to live to be 187 years old, which I plan to do. This reminds of the story of Terry Tempest Williams’ mother. Each year, writes Williams (in When Women were Birds, I think), her mother would put a new notebook on the shelf with that year written on the spine. When Williams’ mother died, she left the notebooks to her daughter: when Williams finally got to look into the notebooks, she found they were all totally blank. Williams writes a whole book about what that might mean. Maybe I’ll just put dates on all my fresh notebooks and leave them to my daughters.