We moved to Calle Animas—Spirit Street—in San Miguel de Allende just as the jacarandas were coming into bloom. When we rented the place, I was leery of the three dogs on the rooftop next door, but once they got used to our routine of spending the sunset hour on our neighboring terrace, they were blessedly quiet. Our mornings, however, were thunderous. We’d wake shortly before dawn to deep poundings in the water pipes. We called our house manager, who sent her master-of-all-trades handyman, but by the time he arrived at a decent hour, the pounding had stopped.

It wasn’t until I went up to the roof with my morning coffee to watch the sun rise that the mystery was solved. A woodpecker was clutching the plumbing stack that rose from the roof, pecking as if its little bird life depended on it.

What Goes Thump in the Night

Woodpeckers are hard to miss. I knew the eastern Canada species pretty well—Downy, Hairy, Red-bellied, Pileated, Northern Flicker, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker—but this woodpecker was new. Its back was thinly barred, like a Red-bellied’s, with a crimson splash on top of its head that bled down into the yellow splotch at the back of its neck, staining it orange. The bird was a skitch bigger than a Hairy, and its bill looked enormous, thick and black, set off by a bright golden aviator’s moustache.

Woodpeckers are hard to miss. I knew the eastern Canada species pretty well—Downy, Hairy, Red-bellied, Pileated, Northern Flicker, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker—but this woodpecker was new. Its back was thinly barred, like a Red-bellied’s, with a crimson splash on top of its head that bled down into the yellow splotch at the back of its neck, staining it orange. The bird was a skitch bigger than a Hairy, and its bill looked enormous, thick and black, set off by a bright golden aviator’s moustache.

I should have known that the predawn sound we heard wasn’t faulty plumbing. I’d been tricked before. When we first moved to the country north of Kingston, I heard a tractor struggling to start. Every morning, every evening, some farmer was confounded by his spluttering machinery—or so I thought until a neighbour explained the sound was a Ruffed Grouse rotating its wingtips back and forth in dramatic crescendo.

Language Without Words

The last time I saw Louise de Kiriline Lawrence, I picked her up from her residence and took her back to her forest on Pimisi Bay. As we walked the path to her log house, she spotted a woodpecker nosing up a branch. She bent to her cane and knuckled a sharp tattoo along its side: two firm raps, then a staccato roll, and a triple ritardando. The bird cocked its head, dug its talons deeper, and drummed a responding ra-ta-tatatata-ta-ta-ta.

“You see,” she whispered, “we still understand each other.”

Louise de Kiriline Lawrence was among the first to describe drumming as language. Her scientific life’s work was a monograph on the comparative life histories of the four woodpeckers that nested in her northern woods—Hairy, Downy, Northern Flicker, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker. She was the first to record a life history of that sapsucker, and the first to compare the movements, gestures, and sounds of these four woodpeckers. (Published in 1967, Louise’s monograph is still cited on the Hairy Woodpecker page of Cornell’s Birds of North America website.)

What sounded to me like a Golden-fronted’s unsophisticated hammering was in fact a nuanced communication that identified the drummer not only as a carpentier, the Spanish word for woodpecker, but as a Golden-fronted, a male. To another Golden-fronted, the particular length of the drumming might identify this fellow specifically as Sr. Carpentier de Calle Animas. The rate at which he tapped indicated his emotional state: a casual morning rap around his territory, a yearning signal to a potential mate, a frantic warning to an intruder.

Our Local Patch

For a month, the Golden-fronted Woodpecker was our reliable alarm clock. Knowing it was a bird instead of an airlock in the pipes, we welcomed his early-morning conversation. While the White-winged Doves sang the sun up into the sky, the Golden-fronted marched the day forward with a military tattoo. Our plumbing stack was the highest branch-like object in the barrio, and it resonated better than any piece of wood. One morning, I took a walk while the bird was drumming: I could hear our carpentier three blocks away.

Cassin’s Kingbirds gathered in the trees. A Cactus Wren sang on the wall beyond my desk. A shimmer of Violet-crowned and Broad-billed Hummingbirds zoomed our garden feeders. Vermilion Flycatchers swooped overhead. In Parque Juarez, we saw a zipper of Gray Silky-flycatchers, their long tails weaving among the branches. Palm Warblers pecked among the debris by the arroyo and Bush Tits raced among the palms. Great Egrets in full feathery breeding plumage nested in the trees above the Casa de Cultura. Great-tailed Grackles stalked the paths like snooty maître d’s, bills in the air.

Cassin’s Kingbirds gathered in the trees. A Cactus Wren sang on the wall beyond my desk. A shimmer of Violet-crowned and Broad-billed Hummingbirds zoomed our garden feeders. Vermilion Flycatchers swooped overhead. In Parque Juarez, we saw a zipper of Gray Silky-flycatchers, their long tails weaving among the branches. Palm Warblers pecked among the debris by the arroyo and Bush Tits raced among the palms. Great Egrets in full feathery breeding plumage nested in the trees above the Casa de Cultura. Great-tailed Grackles stalked the paths like snooty maître d’s, bills in the air.

At sunset, Great Kiskadees called to each other from the tips of the jacarandas, and like clockwork, hundreds of White-faced Ibises etched across the horizon from the canyon presa to the Rio Laja where they spent the night.

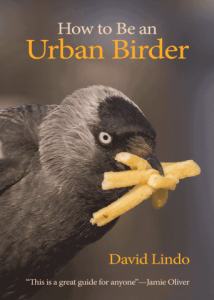

Without leaving the streets of San Miguel, we saw dozens of species on what David Lindo calls “our local patch.” Also known as The Urban Birder, David encourages people to get to know the birds that share not just the fields and forests, but also the streets and alleys and parks. David, who lives in London, England, and is waiting out the pandemic in Mérida, Spain, will be appearing live-on-Zoom at the Springsong Virtual Gala on May 8. You can watch his “Local Patch Video” on the YouTube Channel of the Pelee Island Bird Observatory, a Gala host.

Without leaving the streets of San Miguel, we saw dozens of species on what David Lindo calls “our local patch.” Also known as The Urban Birder, David encourages people to get to know the birds that share not just the fields and forests, but also the streets and alleys and parks. David, who lives in London, England, and is waiting out the pandemic in Mérida, Spain, will be appearing live-on-Zoom at the Springsong Virtual Gala on May 8. You can watch his “Local Patch Video” on the YouTube Channel of the Pelee Island Bird Observatory, a Gala host.

Bird Lesson #4

Creative writing teachers often tell their students, “Write what you know.” I’ve always balked at this dictum, the dull familiarity of it. Instead I say, “Write what you don’t know. Write what you want to know.” Writing for me is exploration, and living half the year in Mexico sets me in a physical and human culture about which I know almost nothing at all.

Creative writing teachers often tell their students, “Write what you know.” I’ve always balked at this dictum, the dull familiarity of it. Instead I say, “Write what you don’t know. Write what you want to know.” Writing for me is exploration, and living half the year in Mexico sets me in a physical and human culture about which I know almost nothing at all.

But travel is just a sweet memory now. The pandemic has made locals of us all.

But travel is just a sweet memory now. The pandemic has made locals of us all.

For a year, I’ve bemoaned my narrowed vista, my shrunken writer’s palette in the north, but I have been blinkered by what I saw as commonplace. From my window, I watch a pair of Mourning Doves feed on a dried-up Christmas wreath still fastened to a door across the way. When we hurried back from Mexico last spring, we set up a feeder in the cedars that border our front terrace, but neighbours complained about the “mess” left by the Song Sparrows and Purple Finches, and front-of-house feeders were banned. Yet the doves continue to forage, waking us in the morning with their soft coo-whoo-coo, coo-coo, a language I have yet to parse.

3 Comments

Lovely! As someone relatively new to the joy of feeding and watching birds I appreciate these observations. And I say that as a committed environmentalist who planted 265 trees in our back yard some thirty years ago to bring in the wildlife. The result was that the wildlife, birds included, spent all their time in the forest, and at its edges. The feeding stations close to the house have brought them into my view. The result? I’m besotted by birds.

Besotted is the perfect word. What a wonderful consequence of all your tree-planting! Kudos to you.

We drive by Pimisi Lake and the historic plaque briefly telling its story of Louise de Kiriline Lawrence almost every weekend, regardless of the state of the pandemic. Our cabin and writing studio is seven minutes from Mattawa, the driveways between the cabin and our home in North Bay precisely seventy kms. Woodpeckers visit often in the woods that are my back yard and a yellow-bellied sapsucker left behind evidence of a nest in the grove in front of our place. I know your book next year will be of great interest to people in this area. Steve Pitt, a writer friend in Rutherglen, was involved in the plaque project. Looking forward to it.