When Helen Keller was eleven, she wrote a story called “The Frost King.” The Perkins School for the Blind published it in their alumni magazine. Almost immediately, Helen was accused of stealing the idea from Birdie and his Fairy Friends, a book she’d never heard of. Her teacher, Anne Sullivan, discovered that someone had, in fact, read the book to Helen when she was eight, finger-spelling the words for the blind, deaf child. Helen had no memory of this. For hours, the girl was grilled by a jury of teachers. She was absolved, narrowly, but the ordeal triggered a nervous breakdown. She never wrote fiction again.

There is a name for her forgetting: cryptomnesia, a kind of memory glitch that recalls an event or an idea not as a memory, but as one’s own original thought.

There is a name for her forgetting: cryptomnesia, a kind of memory glitch that recalls an event or an idea not as a memory, but as one’s own original thought.

Unfortunately, Helen’s story was published at the end of the 19th century, at the height of plagiarism mania. Accusations were so rampant that Anatole France said wryly, “It is great luck, nowadays, if a celebrated writer be not treated, at least once a year, as a thief of ideas.”

The Sincerest Form of Flattery

Until the 17th century, using other people’s words wasn’t only common, it was expected. Authors saw it as a kind of endorsement. Benjamin Franklin, for instance, never denied the blatant borrowing in his Poor Richard’s Almanack, first published in the 1730s. Neither did he credit the authors.

Then, in the latter part of the 1800s, things changed. Spurred by the culture of Romanticism, originality became the Holy Grail. Now, in answer to the perennial question, Where do you get your ideas? writers are unlikely to answer, From a book I was reading. Instead, they’ll say, A voice came to me in the night. Or, Something like this once happened to me.

Such answers are far cry from Mark Twain words in his letter of commiseration to Helen Keller: “All ideas are secondhand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources.”

Begged, Borrowed, Stolen

Did George Orwell, writing 1984, knowingly lift the theme and various plot points from We, an obscure novel by Yevgeny Zamyatin? Was Yann Martel, writing Life of Pi, aware of how it resembled Max and the Cat, a novella by Brazilian Moacyr Scliar? Did Graham Swift, writing his Booker-winning novel Last Orders, intentionally model its narrative line (carrying a body to its final resting place) and its form (chapters told by various members of the burial party) on William Faulkner’s, As I Lay Dying?

Did George Orwell, writing 1984, knowingly lift the theme and various plot points from We, an obscure novel by Yevgeny Zamyatin? Was Yann Martel, writing Life of Pi, aware of how it resembled Max and the Cat, a novella by Brazilian Moacyr Scliar? Did Graham Swift, writing his Booker-winning novel Last Orders, intentionally model its narrative line (carrying a body to its final resting place) and its form (chapters told by various members of the burial party) on William Faulkner’s, As I Lay Dying?

And even if they did, is that plagiarism? Or is it what Jonathan Lethem calls in his brilliant, eponymous essay, “the ecstasy of influence.”

Letham cites William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, a novel riddled with bits and pieces from other works. Not plagiarism, says Letham, rather, “Burroughs was interrogating the universe with scissors and a paste pot.”

Digital Skulduggery

The Internet has changed not only how we do things, but how we think about what we’re doing. A student in the 1980s could plagiarize an arcane source with little fear of being caught. Today, essays are run through digital plagiarism-detectors that can spot word-theft in a nanosecond. Yet, it is digital technology that has made it so easy for artists of every stripe to dip their hands into almost any writer’s cookie jar full of ideas, plots, and characters.

If a computer could read a book, it would remember every phrase and character gesture in its easily accessible RAM. But we are human. Our memories are vast and chaotic: who knows what tidbit will rise up to bump against another, sparking something new. Even brain scientists admit that imagination, like memory and consciousness itself, is a mystery.

If we are ravished by a book—as we are meant to be—how can we not carry some of its DNA in our literary bloodstream?

Literary Remix

We are once again in an era of plagiarism panic. Facebook, Twitter, and the Internet explode with denunciatons and shrill defenses.

Sadia Shepard’s story “Foreign-Returned,” published recently in The New Yorker, follows closely the Mavis Gallant story “The Ice Wagon Going Down the Street,” published in The New Yorker in 1963. The stories follow similar arcs, except that Shepard replaces Gallant’s Canadians struggling in post-World War Two Geneva with a Pakistani family trying to settle themselves in Trump-time Connecticut.

Sadia Shepard’s story “Foreign-Returned,” published recently in The New Yorker, follows closely the Mavis Gallant story “The Ice Wagon Going Down the Street,” published in The New Yorker in 1963. The stories follow similar arcs, except that Shepard replaces Gallant’s Canadians struggling in post-World War Two Geneva with a Pakistani family trying to settle themselves in Trump-time Connecticut.

Francine Prose called it a “scene by scene, plot-turn by plot-turn, gesture-by-gesture, line-of-dialogue by line-of-dialogue” copy. Shepard had already acknowledged her debt to Gallant in an interview released with the story. Mavis Gallant’s work of fiction, she said, was one she returned to over and over, struck by how it paralleled her own experience. In her view, she wasn’t plagiarizing, she was translating the universal truth of Gallant’s story into a different time and culture.

Jeremy Gavron, who wrote about the fracas in The Guardian, himself just published a new novel, Felix Culpa, composed almost entirely of lines borrowed from 100 books, most of which, he writes, “are the novels and other works that have shaped me as a writer.”

Liars and thieves

Neil Gaiman echoed Plato when he wrote, “Writers are liars, my dear, surely you know that by now?” Picasso said, “Art is theft.” TS Eliot was more specific: “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.”

Poets have long since formalized their so-called thievery. Among the 90 or so poetic forms is the ‘cento’—Latin for patchwork—made up entirely of lines from other poets. “Found poems” are built with bits stolen from the world at large. “Collage poems” intersperse lines from other poems with the writer’s own words.

An online poetry workshop suggests that writing these purloined poems not only illustrates the importance of context, it teaches writers how text can be disassembled and reassembled to create something new. Through the mixing of work, the poems “talk to each other.”

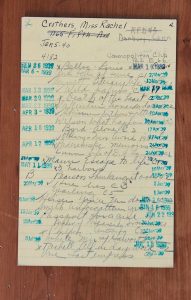

Prose writers have no formalized structures for incorporating the work of others. In fact, originality is particularly revered in the novel, a word that signifies new and unusual. Thanks to the New York Society Library, however, we do know what some writers were reading while they wrote. Lillian Hellman was reading Faulkner the year The Autumn Garden premiered; Roald Dahl, author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and James and the Giant Peach, had a penchant for MFK Fisher food memoirs; and while Herman Melville was writing Moby Dick, he checked out a book on whaling that he held onto for thirteen months.

Silencing the Echoes

The notion of literary influence interests me because in Refuge, my novel coming out in September, I pay homage to many writers. When I first started the story of a woman who lives through the twentieth century, the structure was chronological. I had the idea of writing each decade in a style of its time. I chose writers I admired and studied their forms, their language, even their punctuation quirks. I’ve always thought of myself as a magpie writer, but suddenly I was a mynah, my voice braided with literary mimicry.

The structure didn’t work. In the end, I rewrote the story in the present with chapters that dip into the protagonist’s past. Once the novel was in her voice, the mimicry made no sense. Painstakingly, I redrafted the chapters, ripping out all echoes of Martha Ostenso, John Steinbeck, John dos Passos, Gabrielle Roy.

Do hints of these great writers still linger? I wouldn’t be surprised. The novel was 14 years in the making and I don’t remember all that I added, but I do acknowledge my debt to them.

The Anxiety of Influence

In 1973, the critic Harold Bloom published The Anxiety of Influence, an exploration of the relationship of artists to their predecessors. In his view, no poem was entirely original. Influence was not only unavoidable, it was natural to the creative process as writers absorb, to varying degrees, both style and content from the artists they admire.

In 1973, the critic Harold Bloom published The Anxiety of Influence, an exploration of the relationship of artists to their predecessors. In his view, no poem was entirely original. Influence was not only unavoidable, it was natural to the creative process as writers absorb, to varying degrees, both style and content from the artists they admire.

In the digital age, the anxiety of influence is ramped up. When does influence shift to plagiarism? When does a thoughtful recasting of someone else’s work become theft?

Surely these are questions of degree and intent.

In a judgment known as the Feist case, the US Supreme Court declared that “ideas are freely available but that the expression of the idea can be protected.”

A writer’s mode of expression is words. How many words am I allowed to use without raising an alarm? According to the plagiarism-detectors, 16 identical words in identical sequence are almost certainly copied. TurnItIn.com adds, “the likelihood that a 16-word match is ‘just a coincidence’ is less than 1 in a trillion.”

Payback

Today we take ownership of creative intellectual property as a given, in the same way that freewheeling copying was the norm 400 years ago.

In the early nineties, when my sons were starting out on their own careers as a musical and a visual artist, they argued eloquently against my hardline view of copyright, in which the creator holds all the cards. I see their point now: copyright is wedded to an outmoded notion of originality that does not admit the collective experience fundamental to the creation of art.

For me, it boils down to this. If a corporation is using my words for profit or a school is copying my words as a way of avoiding buying books, then yes, give me a token payment in return. And if you want to adapt my story to a different form—a play, a movie, a symphony—then pay for that, too.

But far more important to me than money is acknowledgment, because when a source is named, that book becomes part of the cultural conversation. Each acknowledgment leads me—as a reader and a writer—to another book, a new idea, new ways of looking at the world.

I want to be influenced. I stand on a soaring pillar of all the books I’ve ever read, a foundation that lifts me up and shows me how my flash of an idea might be shaped into words. Now and then, the pillar is something I have to shove against, and something new can come of that, too.

I want to be influenced. I stand on a soaring pillar of all the books I’ve ever read, a foundation that lifts me up and shows me how my flash of an idea might be shaped into words. Now and then, the pillar is something I have to shove against, and something new can come of that, too.

As Jonathan Lethem says: “Don’t pirate my editions; do plunder my visions. The name of the game is Give All.”

It’s a new game, one we’ve played for centuries.

1 Comment

I just read Pasha Malla’s essay in the Literary Review of Canada: https://reviewcanada.ca/magazine/2017/12/against-originality/

We come to our conclusions independently, and Pasha at much greater length, but there is a remarkable likeness in our thinking. As he says: “framing literature as a practice of singularity and uniqueness obscures its communal roots.” He notes, accurately I think, the lack of informed dialogue on the subject. “All writing is of course indebted to its antecedents, yet a culture whose dialogue with history exists almost exclusively in terms of nostalgia, and which values the exclusivity of the new over all else, seems to be influencing how we think about books—as if each title exists as a shining jewel of originality, less in conversation with the rest of literature than in competition with it.” Two Canadian fiction writers thinking and talking about this—could it be a trend?