[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] After seven years of researching and writing, I finally printed out a draft of my nonfiction novel The Convict Lover. The stack of pages was higher than a child’s booster seat. Even in my innocence, I knew prospective publishers were unlikely to read a 750-page prison tome, so I hauled out my scissors and glue pot—this was 1994, the digital dark ages—and attacked my hard-won words. Six months later, the manuscript was lean and muscular, reduced to a mere 88,000 words from its original 200,000. My heart, along with countless, priceless scenes, lay in shards on the floor.

Under the Influence

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]When Helen Keller was eleven, she wrote a story called “The Frost King.” The Perkins School for the Blind published it in their alumni magazine. Almost immediately, Helen was accused of stealing the idea from Birdie and his Fairy Friends, a book she’d never heard of. Her teacher, Anne Sullivan, discovered that someone had, in fact, read the book to Helen when she was eight, finger-spelling the words for the blind, deaf child. Helen had no memory of this. For hours, the girl was grilled by a jury of teachers. She was absolved, narrowly, but the ordeal triggered a nervous breakdown. She never wrote fiction again.

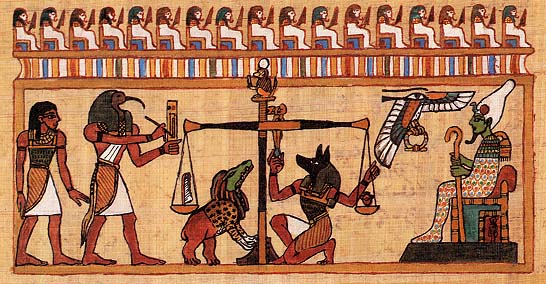

Books of the Dead

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]”The Weighing of the Heart,” one of 192 spells, incantations, and rituals that make up The Book of the Dead, describes how the heart of a deceased will be set into a tray on one side of a large scale. In the other tray, a feather from Ma’at, goddess of truth. If the heart balances the feather of truth, the dead may continue their journey into the afterlife. If the heart outweighs the feather, Ammat the devourer—a crocodile-headed creature with a cat’s body and hippopotamus hindquarters—will snatch the human heart from the scale and gobble it down.

Read more

A Brand New Breed (of Books)

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Imagine listening to Maggie deVries’ Rabbit Ears in Vancouver’s downtown east side, among the runaways, addicts, and women of the street she portrays. Or any David Adams Richards book while walking the shore of the broad Miramichi. Or canoeing north of Yellowknife in the company of Liz Hay’s Late Nights on Air. Now imagine a story written to take you to a specific place, where what you see and hear and smell dives you deep, deep, deep into the words. That’s ambient literature.

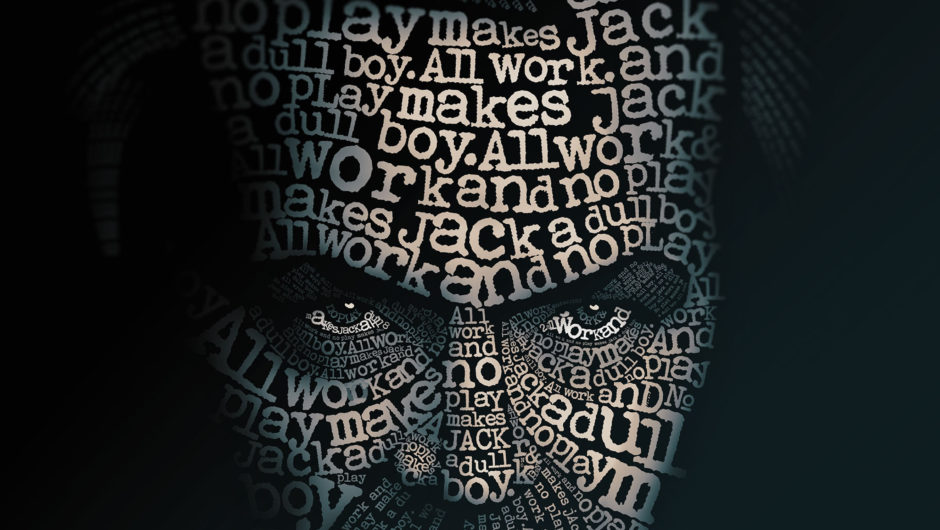

Face Time

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Over the course of a hundred nights, a hundred years ago, a dark figure heaved bag after heavy bag off the Hammersmith Bridge into the River Thames.

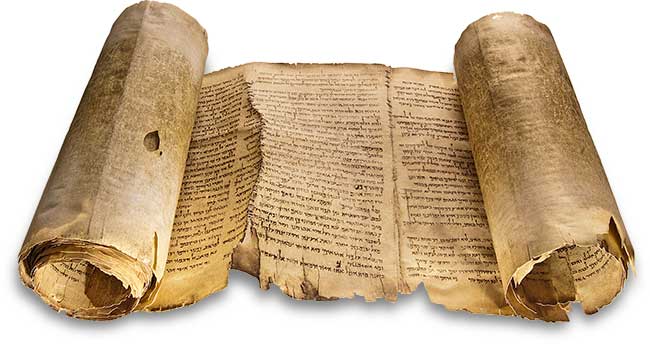

Scrolls, Tablets, and Scrolling Tablets

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] 2017 is the 40th anniversary of the personal computer and the 25th anniversary of the first ereader. A quarter century and millions of ebooks later, writers and readers, friends and pundits are still arguing over whether this is a good way to read books.

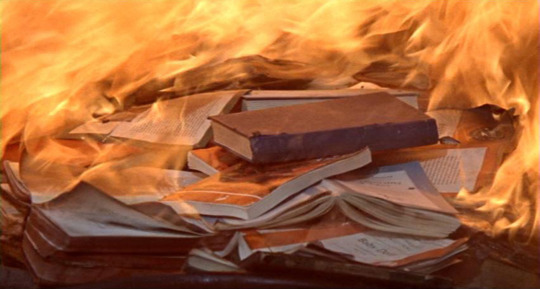

How to Disappear/Save a Book

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Madeleine Thien’s Giller- and GG-winning novel, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, is set partly in China in the culturally turbulent years after the Second World War. Two sisters, Swirl and Big Mother Knife, are story-tellers who travel the country performing story cycles. “Stories, even in times like these, were a refuge, a passport, everywhere.”

Recent Comments