[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Paper is not forever: it can be burned, cut, torn, crumpled, lost; it can rot, discolour, disintegrate; be eaten away by mice and mould. Even so, it is more enduring than what we think or what we say. It has the strength to carry words across vast landscapes and through millennia, from one person to hundreds, thousands, even millions.

The Flight of Birds throughout the Air

In 1815, John Adams, the second president of the United States, wrote to his grandsons as they were preparing to cross the Atlantic to join their parents: “Without a minute Diary, your Travels will be no better than the flight of Birds throughout the Air. What you write, preserve. I have burned Bushells of my Silly notes, in fits of Impatience and humiliation, which I would now give anything to recover.”

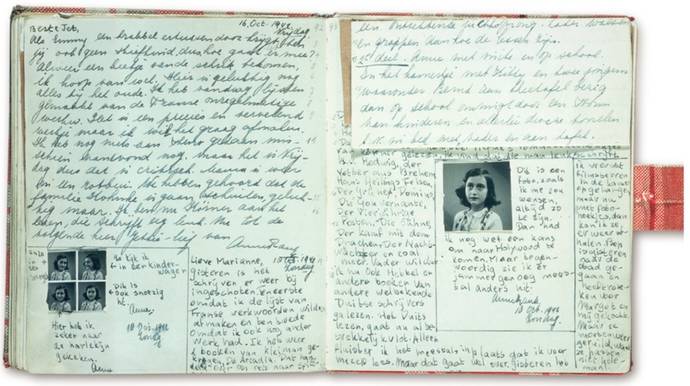

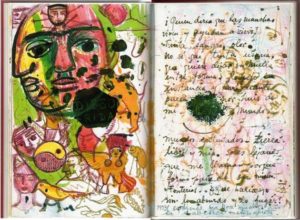

I received my first diary as a going-away gift when I was seven, on my way to Brazil with my family. I wrote in it daily until I was a young woman and I’ve kept one sporadically ever since. I’ve never thrown them away or burned them, but neither have I been a consistent recorder of time’s passage. When I visited Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul in Coyoacán, I was filled with guilt and longing at the sight of her rows of boxed diaries, bulging with clippings and sketches and her impressions, what seemed like every moment of her life.

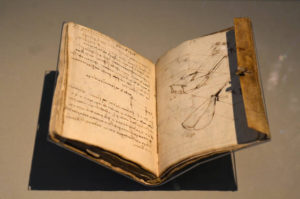

Leonardo da Vinci, one of the world’s great diarists, left 13,000 pages of notes containing his observations, speculations, plans, and fantasies. The printing press was brand new when he was born in 1452, and paper had just arrived in Italy 200 years before.

What if there had been no paper? Would he have scratched his ideas in the sand? Painted them on a wall? He could have used parchment or vellum, but the skins of animals were expensive and relatively scarce, the purview of scribing monks. The supply of paper must have been limited, too, yet Leonardo didn’t stint. Of his finished works, only some fifteen paintings and a few sculptures survive: his reputation rests mostly on the enormous body of sketches and notes for his precocious inventions, all recorded for the future on paper in his mirrored script, the movement of his hand visible in the ink on the page.

Virginia Woolf, Anne Frank, Goebbels, Hemingway, Samuel Pepys, Sylvia Plath, Anaïs Nin, Henry David Thoreau: imagine a world without its diarists and correspondents.

Villa of the Papyrus Scrolls

Almost two thousand years ago, the eruption of Etna buried not only Pompeii, but the town of Herculaneum and a nearby mountainside villa belonging to Julius Caesar’s father-in-law.

In 1752, the villa was excavated from within its ninety foot-foot tomb of stone and ash. Among its splendidly intact loggias and galleries was the only private library that survives from antiquity: a small room housing hundreds of papyrus scrolls stacked horizontally on shelves: 800 books in all, which some believe represent only the anteroom to the main library of what has come to be called the Villa die Papyri—the Villa of the Papyrus Scrolls.

Ironically, the ash that charred, then interred the papyrus also preserved this first paper. But in a twist that sounds like a fairy-tale curse, the second the scrolls are exposed to air, they start to deteriorate and disappear.

In the 265 years since their discovery, various means have been used to try to soften the scrolls enough to unfurl them: rose water, mercury, papyrus juice, and, most recently, a cocktail of glycerin, ethanol, and warm water. Nothing worked.

News from an Ancient Empire: “Would Fall”

Finally, last year, the Smithsonian reported that a Stanford physicist got permission to put one of the Herculaneum scrolls—a gift to Napoleon and now housed in France—through a synchrotron, a kind of accelerator that can be “tuned” to look for certain particles. Like magic, the iron-gall ink on the ancient papyrus became visible. Without physically touching the charred remains, a French team found writing scattered across the unscrolled papyrus and thus far has managed to make out one chilling phrase—“would fall.”

Digital technology, accused of killing the paper book, may yet succeed in saving a whole library.

We say we “keep a diary.” More to the point, a diary—like a book, like a scroll—keeps us on its crumbling, rotting paper pages. Such a fragile substance to carry so heavy a burden: news of a life, a place, of time itself.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364023324{padding: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

Question:

What writing, preserved from the past on paper, has made an impact on you?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Comments

Hi Merilyn

Wonderful. Love this. I sometimes look at all the old letters and diaries from both sides of my own family and my first husband’s family (deceased 1981) and I love what they tell us now about their emotions and thoughts as they lived their lives. Now, our family communications are so ephemeral –emails etc.–and what will be left…. A question perhaps to explore in blogs.

I also remember when I was in grad school standing in front of the Gutenberg Bible in Harvard’s rare book section with its curator. The only thing that comes close is seeing the first Gospel of Mark on the Island of Patmos in Greece and finding to my delight that I could read the open page. . Thanks for exploring all this with us.

Merilyn – I must have been waiting for someone to ask the question you just did. I thank you for making me put my answer into words.

I traveled to Vancouver in September to visit Sybil, my beloved lifelong friend from childhood, now terminally ill. We met when we were eight, sixty years ago.

We were joined in Vancouver by another friend, who Sybil and I met at our first day of college, Michigan State University, 1966. Tellingly, all three of us had saved our letters to one another since the 1970s – written when we moved to other cities, changed schools, or traveled the world. Tellingly, because each of the letters shares the story of our life at that moment, and each of us must have known, somehow, that these stories were meant to be saved and cherished one day with each other, far into the future.

We didn’t think that future would come so soon.

But this September, Barbara, Sybil and I reopened the envelopes, many written on thin, blue airmail paper when traveling the globe, and reread the letters to one another. The anticipated laughter and tears never stopped. Laughter when we could barely remember the last names of “boys” we believed had irreparably broken our hearts. Cried when reading of moments and milestones when our hearts were touched, in kinder ways.

After a few hours, the reading became too much emotionally. How happy and sad these letters made us! We folded the read ones up, tucked others away.

That night, Sybil’s 26 year-old daughter and friend joined us for dinner. We told them how we had spent the day. They were dumbfounded. Hand-written letters? Pages and pages of them? On both sides? Saved in boxes, some for over 40 years? Yes, they contained the minutiae of our days, our surroundings, our feelings, hopes,, dreams and anger.

Michelle and Dorah laughed hearing our stories. “That is SO sweet,” said Michelle. “We’ll never have that, Dorah. We just text. And we don’t really say much, anyway, do we?” Dorah suggested they keep journals. They were excited at the thought, but to me, the thought seemed fleeting.

My feelings have remained bittersweet since putting the letters back in their cardboard box once I returned home. Sweet because the moments spent rereading our letters were beyond precious. Sad, a better word for me than bitter, because I’m afraid the reason I saved the letters all these years may have come and gone.

No matter. Probably one of the smartest things the three of us ever did – not only writing those letters, but holding onto them all these years.

Highly recommended.

That is so touching. What a wonderful story to share. Thank you.