On a balmy Sunday like today, when we are in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, we taxi up to El Charco del Ingenio before the sun is fully up. The Charco is a swath of grassland, dotted with cacti and mesquite, that frames a shallow lake created by damming the stream that cuts through a wild gorge down into the city. Charco del Ingenio translates variously as “puddle of wit,” “water-works,” and “spirit pool.” I prefer the latter.

Great Kiskadee scream at us from the treetops; an American Kestrel keeps watch from the height of an indigenous offering to the four winds. Mexican Finches, Lesser Goldfinches, and Cactus Wrens trill in the bushes while the bushtits swoop in and out like chattering teens. On the lake, the Mexican ducks laugh their Grouch Marx har-har-har. We follow a Vermilion Flycatcher mesquite to mesquite, revelling in its song. The Pyrrhuloxia sounds so much like a Northern Cardinal and the Rufous-backed Thrush so like a robin that we experience a kind of geographical vertigo. And then the orioles—Baltmore, Orchard, Scott’s, Bullock’s—start to sing. We head home along the path through the gorge, buoyed by the chorus. By the time our feet hit the cobbled street that slopes sharply into town, we are as stunned as music-lovers trailing out of a live concert.

Great Kiskadee scream at us from the treetops; an American Kestrel keeps watch from the height of an indigenous offering to the four winds. Mexican Finches, Lesser Goldfinches, and Cactus Wrens trill in the bushes while the bushtits swoop in and out like chattering teens. On the lake, the Mexican ducks laugh their Grouch Marx har-har-har. We follow a Vermilion Flycatcher mesquite to mesquite, revelling in its song. The Pyrrhuloxia sounds so much like a Northern Cardinal and the Rufous-backed Thrush so like a robin that we experience a kind of geographical vertigo. And then the orioles—Baltmore, Orchard, Scott’s, Bullock’s—start to sing. We head home along the path through the gorge, buoyed by the chorus. By the time our feet hit the cobbled street that slopes sharply into town, we are as stunned as music-lovers trailing out of a live concert.

A sign spray-painted on a wall near the bottom of Cuesta de San José shows a wild bird, its bills open in full song, surrounded by a red circle, the universal symbol, without the slash, for “allowed.”

Of course! we think, until we pass a metal door, its top panel a filigree of ironwork. Through it, we can barely make out the courtyard of the house within, and along one side, a row of cages where captive birds sing their songs.

Ask Not For Whom the Bird Sings

Keeping caged birds as pets is a longstanding Mexican tradition. Since before the Spaniards, birds have been kept for their sweet voices and for their beauty, and in the case of parrots and corvids, their intelligence. Some cultures believed birdsong brought the rain. Others saw in songbirds the reincarnated princes and warriors slain in battle. Many heard the sounds of birds as auguries of the future, much as my norteamericano forebears believed a wild bird in the house foretold a death.

Keeping caged birds as pets is a longstanding Mexican tradition. Since before the Spaniards, birds have been kept for their sweet voices and for their beauty, and in the case of parrots and corvids, their intelligence. Some cultures believed birdsong brought the rain. Others saw in songbirds the reincarnated princes and warriors slain in battle. Many heard the sounds of birds as auguries of the future, much as my norteamericano forebears believed a wild bird in the house foretold a death.

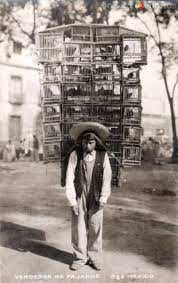

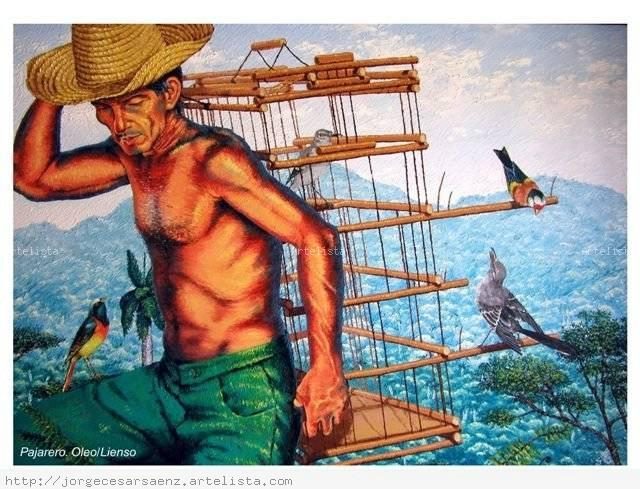

The Mexican bird traders who capture and sell wild birds are called pajareros, from pájaro, Spanish for bird. These men (rarely women) know birds deeply, their habits and habitats. They are plying a trade older than history, one that has been handed down within families for generations. Today, the pajareros are organized into trade unions; more than 500 apply for permits to collect some 96 species of birds, most of them native to Mexico. (Some 1150 bird species make Mexico home.) The bird traders know enough not to capture birds during breeding season, a tradition they have observed forever, they say—desde siempre. They care for the captives for weeks, sometimes months before taking them to market. Fledglings—pollos—have to learn to eat new food; broncos—untamed adults—have to get used to humans.

Cuesta de San José is not the only place we hear caged birds sing. Birdsong seems to rise from behind every wall, and on the streets, from cages that hang low from the branches of linden trees in front of little shops. Bedraggled orioles, waxwings, mockingbirds, buntings, thrushes, and one desperate-looking Rose-breasted Grosbeak peck at their feathers as they huddle on the perches or pace the small cages.

As much as humans appreciate the songs of these captives, they are not singing for us. Kept side by side with others of their species and sometimes with the predators they most fear, the birds are singing in a futile attempt to establish a territory, to attract a mate, to warn off that bird next door which is pacing way too close. Locking them up only heightens their natural drives, and so they sing their hearts out.

The Birdmen of La Placita

At the Tuesday market, a travelling, tented tianguis the locals call La Placita (little city), I hear the pajarero before I see him. He is a walking dawn chorus. From wooden cages stacked against the pajarero’s back, towering high above his head, the cantadores advertise their own sale.

I stop to talk with him, but my Spanish is limited and heavily accented with English, and his is mixed with the cadences of Otomí. But it is clear he knows his birds. He describes each one in detail, what it eats, where it came from, where its cage is best hung.

Birdwatching is new to Mexico, a sport of the leisure class. Binoculars are expensive and rare: even the men who work in nature reserves have rarely seen a bird with anything but their eyes. The pajareros probably know more about birds than anyone. And they are sensitive to ecosystems. When I ask about price, this pajarero tells me his birds are more expensive than they used to be because the forests are being cut down, the berries and the insects are disappearing, so the birds are fewer, harder to catch

Freedom’s just another word…

We could flick open the cages hanging from the linden trees and set the birds free before the shopkeeper noticed, but we don’t. The keeping of songbirds means something different in this culture, something we don’t entirely understand, so we keep a distance. Instead, we listen for a difference in the song of the caged Rose-breasted Grosbeak, compared to the song we know so well in our forests back home—like a robin with singing lessons, as Roger Tory Peterson put it in A Field Guide to Birds of Eastern North America.

If a bird sings in the forest and no one hears it…

The Ontario stay-at-Home order that is our current reality allows a walk in the woods for the purpose of exercise. The rule-makers are silent on whether a walk is condoned for the sole purpose of watching birds, but we grab our binoculars anyway, hoping to welcome back the warblers. Every morning and evening for a week we try first one forest path then another. The woods are eerily silent. Altogether we see only a handful of warblers and a few flycatchers; except for the Yellow Warbler, the birds we see are solitary representatives of their species.

Perhaps our timing is off. Perhaps the migrants take a route we never found and they are singing wildly, unheard, as they replenish the fat they lost on their long trip north from mesoamerica. Or perhaps their numbers are dwindling more drastically than we thought—and will continue to dwindle until the caged bird is the only one we’ll hear sing.

Bird Lesson #5

I am perplexed by these birds in cages, singing their familiar tunes. If the only time I see a particular species is in a cage, far from its natural habitat, eating food unlike any that nourished it in the wild, singing from behind delicate wooden bars, can I really say I know that bird?

And how different is a caged bird from one whose diet consists primarily of mass-produced peanuts and sunflower seeds—food it would rarely, if ever, eat in the wild? I thrill to the clutch of a chickadee on my finger as it snatches a seed from my outstretched palm, and I stock my feeders with seeds and fruit and sweet nectar to draw the birds in close, but in doing so, am I not guilty, too, of interfering in their natural lives?

Louise de Kiriline Lawrence maintained feeders for hundreds of birds over several decades until she had a radical change of heart and dismantled them all. “Wildness, the wild creature’s most vital asset of self-preservation, is lost,” she wrote in To Whom the Wilderness Speaks. “Lost is the daring, the spark that fires the successful escape, blunted is the instinct to avoid the too-close approach of a stranger.”

These days I see far more people caged on screens than I see in real life. I struggle to recall not an actor’s facsimile, but the true face of grief, unrehearsed paroxysms of joy. “Readers have a nose for authenticity,” Tommy Orange said to me late one night as we sat together in the far corner of a Mexican garden. “They can smell it if you’re not telling the truth.”

I think of this as I fit words into sentences, in search of the wild, uncaged heart.

1 Comment

Thanks for your eloquence, Marilyn. Selling and keeping caged birds was only one of many unfamiliar and unappealing customs we had to adjust to during our three-year stay in Kenya. Back home in Ontario we took down our backyard bird feeder after catching sight of a large rat feeding below on the spilled seeds. Happily for us, many kinds of birds continue to nest within the backyard cedar trees; robins, sparrows, grackles and cardinals are the most numerous. In winter they seem unconcerned about our kitchen activities, and every spring they slowly get used to our gardening motions. This accommodation feels more comfortable than cages for them or rats for us!