Writing used to mean penmanship. Then it became a profession, a conveyor of stories and facts. It has always been a radical act.

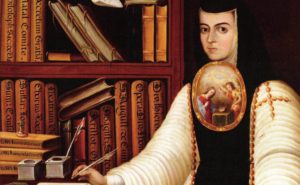

Three hundred and fifty years ago, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Mexico’s first poet, complained bitterly that, inside her convent, decent handwriting was forbidden. A brilliant self-educated woman, portrayed in a biography by Octavio Paz and in the hefty Canadian novel Hunger Brides, Sor Juana became a nun at the age sixteen in order to have freedom to study. Instead, she came up against punishingly restrictive rules.

“Even making my handwriting somewhat elegant cost me a long and brutal persecution, only because they said that it seemed like a man’s handwriting, and that it was something indecent. With these judgments, they obligated me to make it worse on purpose.”

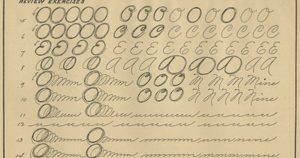

By the time Mexican novelist Margo Gantz came along in 1930, the tables had turned. Good penmanship in a woman was now an essential signature of good character. She recalls learning the Palmer Method of English penmanship in her Mexico City classroom.

“All day long I did exercises with a penholder, a pen, and an inkwell, and those exercises always turned out disastrously. There were always smudges. Anyone who didn’t write well had to write a hundred times:

I’m a dirty little girl, I don’t have good penmanship, I can’t even copy the letter A.

Uncertain Futures

Margo Glantz’s parents emigrated from the Ukraine. They wanted to settle in the United States, but that country slammed its doors on Jews, so they ended up in Mexico, where her father became close friends with Diego Rivera.

When she was growing up, her only literary model was the Palmer Method, which taught her that, “All you need to be a good writer is good penmanship. What’s more, good penmanship alone will produce a brilliant writer.” Ergo, without good handwriting, she couldn’t possibly be a good writer.

Glantz once gave a lecture at Princeton University on the relationship between penmanship and writing by women. She talked about how penmanship and the practice of writing has long divided the sexes and social classes—how the act of writing was (and in some places still is) a visible cue by which the entire mental, spiritual, and emotional life of a person is judged.

Anne Trubek talks about handwriting as social arbiter in her book, The History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting. Because handwriting was labour done by hireling monks and scribes, the wealthy were careful not to be too good at it. “The more educated and illustrious you were,” she writes, “the worse your handwriting was supposed to be.”

The Public Life of Penmanship

Rosario Castellanos, the feminist poet, novelist, and essayist who became Mexico’s ambassador to Israel, was estranged from her family when a curandera predicted that one of her mother’s two children would die soon, and her mother screamed out, “Not the boy!” In A Woman Who Knows Latin (Mujer que sabe Latin), Castellanos talks about the power of learning to write:

“I inhabited a realm before language, one of pure sounds that I later learned could be harmonised into sequences and correspondences. It was then that I learned to recite the alphabet…The rhythm is so even and so gentle that it reminds me of the breathing of a sleeping child. I’m no longer the child that death shunted aside in favour of the other one, the better one, my brother. I’m not the girl left alone by her parents to diligently sob away her grief. No. I’m almost a person. I have the right to exist, to stand before others, to…climb onto a podium draped with tissue paper and recite my verses.

She writes a poem in her school notebook and the moment she reads it, “I realize that these two lines engendered in the pit of my belly have just severed their umbilical cord, freed themselves from me, and are now staring me in the face: autonomous, absolutely independent, and even more remarkable, like strangers.

“I don’t recognise them as objects that once belonged to me, but rather as objects that are there, prodding me to acquire a greater, more perfect level of existence: a public existence.”

Character Studies

I fell in love with words early. Words like filigree or Dumbo could make me laugh just from the contortions of my lips. I don’t know exactly when my mouth connected to my eyes and I could say the words I saw, but I do remember the first time I held the point of a sharpened pencil to the page and traced that bulbous a. I’d grip my fat red pencil and track the loop and slide until I got it right, then I’d carry on along the line, drawing the letter again and again. I don’t remember when it dawned on me that what I was doing wasn’t drawing, it was writing.

Suddenly, the alphabet wasn’t only in my eyes and my mouth. It was in my arm, my hand, my fingers. In my tongue that stuck out of the corner of my mouth. In my body leaning against the sharp edge of my desk. In my bum that lifted up off the seat. In my toes in their brown Oxfords that didn’t quite touch the floor. My whole body was wrapped up in that a, and in all the words I’ve written since.

In The Hand: How its Use Shapes the Brain, Language and Human Culture, neurologist Frank R. Wilson gives scientific credence to what I felt. Handwriting, he says, stimulates brain activity and helps develop “deep feelings of confidence and interest in the world-all-together, the essential prerequistes for the emergence of the capable and caring individual.”

The Reincarnation of Cursive

Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple Inc., often cited a course in calligraphy as one of his formative experiences. How ironic, given that computers have pushed penmanship off North American curricula. (We don’t even call it penmanship any more; it’s “cursive.”) Computer script obliterates the human character visible in handwriting. There is nothing to decipher. All traces of process disappear.

On the other hand, computers never smudge. In my class, kids with pretty penmanship were considered “good at school.” Good in general. Now there are no blotted copy-books on which to base such judgments; less to stand in the way of the meaning of the words.

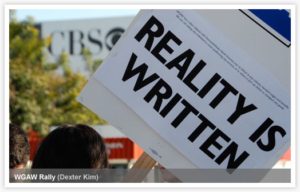

But news of the death of penmanship may be premature. Not only are scientists discovering the hidden values of cursive—when children compose text by hand, they consistently produce more words more quickly than on a keyboard, and they express more ideas—but a glance at images of the massive protests in recent weeks show that hand-writing writ large on placards and banners expresses outrage more clearly than digital printing ever could.

As Yale psychologist Paul Bloom points out, “With handwriting, the very act of putting it down forces you to focus on what’s important.”

Signature Moments

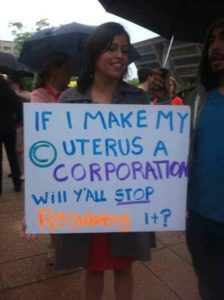

Last Monday, January 23, was National Handwriting Day in the United States. On that day, Donald Trump put his cursive signature to a presidential memoranda that withdraws federal funding from international “organizations or programs that support or participate in the management of a program of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization.”

The memorandum is called, “The Mexico City Policy.”

A line in the sand, a stroke of ink on parchment, digital words on a screen, a slash of paint on an alley wall, a black marker on a poster. We need all the tools we can get our hands on to say what is in our hearts.

No wonder cursive is back.

6 Comments

Lovely post!

I’ve been told that cursive is no longer taught to children in Mexico. The parent who told me this has taken it upon herself to teach cursive to her child. A quick Google search indicates that it is also being phased out in Canada and the US as well. Too bad!

The US took it off the national curriculum in 2011.In Canada education is a provincial concern, so harder to track, but I know Ontario and Quebec pulled penmanship in 2006. Since then, teachers are advised to respond to childrens’ schoolwork in printing, as they may not be able to read words where the letters run together.

I couldn’t agree with you more. About a month ago I was at Tim Hortons and there was an elderly lady making notes in a book she was reading. I excused my self and said, “Did you know that they haven’t been teaching cursive writing in public schools for the last 20 years? She didn’t know that. When I saw her next I gave her a square nib pen and ink. She is now taking a calligraphy course at a seniors centre.

Lovely story, Hugh. Thank you!

I fully support the art of calligraphy and hobby penmanship (penwomanship?), but as a father of two daughters with dysgraphia (a subset of dyslexia where the person can read but not write) I have to caution against it’s mandatory instruction in schools. (It is still part of the curriculum in Alberta Canada, though much reduced from when I was in school). Dyslexia is the single most common learning disability (12-15% of the population) and penmanship is unmitigated torture for these students, doubly so for those with dysgraphia as that disability goes undiagnosed (less obvious than full blown dyslexia) and is frequently interpreted as ‘sloppy, lazy and stupid’. It is not just that these students cannot master cursive (literally impossible) but that the teacher’s impression of lack of effort and ability transfers over to nearly every subject, since their inability to write in cursive manifests in every written assignment in every subject. My daughters would minimize their writing rather than try to write in cursive, with the result that their answers often fell far short of their actual knowledge. Allowed to print they do much better, but–and this is difficult to explain to those unfamiliar with dysgraphia–, have relatively little trouble when permitted to type. Typing, it turns out, uses a different portion of the brain, and their inability to spell (part of the dysgraphia/dyslexia syndrome) can be fixed through a specialized spell check program called Ghotit. So NOT having mandatory cursive instruction dramatically improves the school experience of 12-15% of students. By all means, have penmanship offered as an elective, or as an ART option, but please do not lobby for mandatory part of the curriculum.

In an age of word processing and dictation on computers, there is perhaps a greater need for instruction in typography than cursive. Of my 300 university students each year, only one or two take handwritten notes or write a first draft in cursive. Everyone types their notes and papers, even when doing a first draft. Yet almost none of them have any idea about typography or design, which would indeed be a skill (like penmanship in days past) everyone should have some understanding of, since good design and typography can reinforce one’s messaging and readability. Much of what you have to say in this column would be equally true of typography and design, except looking forward, rather than backward.

Just saying.

Thank you for this really fascinating insight into dysgraphia. I have a left-handed son and while cursive was not impossible, it certainly would have been torture. I am not advocating for a return to the days of Palmer! But I do know from my own experience as a writer and a mentor that engaging the body in the work of the mind has its benefits.