[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]In the Café Gluck on the outskirts of Vienna, in the fading years of the Empire, Jakob Mendel sits surrounded by heaps of catalogues and books. An itinerant bibliophile denied a license for permanent trade, he sets up at a table when the café opens and stays until closing, his portable bookshop a secret except to the initiated. Even so, his book table is a mecca for booklovers and collectors, for Mendel is blessed with the magic of perfect memory and knows the contents of every book he sells — a mind stuffed fuller more than any expert, any librarian, any corporate whiz.

In “Mendel the Bibliophile,” a masterful and surprisingly contemporary story published in 1929, Stefan Zweig not only draws an iconic portrait of the bookseller but captures the essence of the perfect bookshop—part shrine, part life-giving fountain of knowledge, part communal gathering-place.

Story Pedlars

In 4th century BCE Athens, it was the rise of libraries that created procurers devoted to buying up books and selling them to public and private hoarders. In Rome, where the personal library became an indispensable part of domestic architecture, booksellers listed books for sale on the door posts of their shops— their taberna librarii.

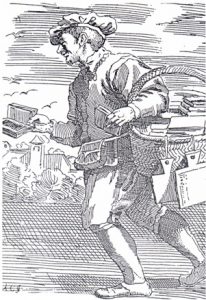

Scribes in medieval Europe were granted legal ownership of the material they copied and thus supplied copies of books on demand. Similarly, the first printers after Gutenberg became booksellers. For those who lived in outlying regions, books were sold much as Mendel conducted business: booksellers were pedlars, offering missals and chapbooks along with egg beaters and cures for rheumatism. It wasn’t until the 19th century that a clear distinction was made between publisher (the producer of books) and bookseller (literary promoter and seller of books).

A Place for Books

“The way a specific story relates to the whole of literature is similar to the way a single bookshop relates to every other bookshop that exists, has existed and will perhaps ever exist,” writes Jorge Carrión in Bookshops, A Reader’s History, which opens with “Mendel the Bibliophile.”

“The way a specific story relates to the whole of literature is similar to the way a single bookshop relates to every other bookshop that exists, has existed and will perhaps ever exist,” writes Jorge Carrión in Bookshops, A Reader’s History, which opens with “Mendel the Bibliophile.”

Bookshops—bookstores to North Americans but bookshops to the rest of the English-speaking world—sell books, but what makes them so dear to the hearts of book lovers?

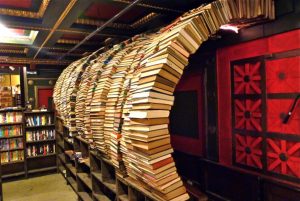

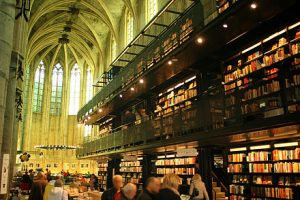

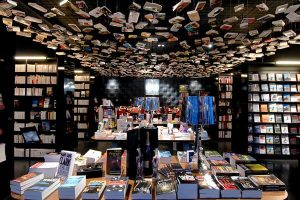

Is it because books themselves are beautiful? Bring them together in beautiful spaces, and the result is inspirational. The Polare bookstore in Maastricht is housed in a 13th century converted Dominican church. The books in El Ateneo in Buenos Aires are stacked where plush seats once graced the Teatro Gran Splendid. The Librairie Avant-Gard in Nanjing, named China’s most beautiful bookshop, is housed inside a government car park that was once a bomb shelter.

Is it because books themselves are beautiful? Bring them together in beautiful spaces, and the result is inspirational. The Polare bookstore in Maastricht is housed in a 13th century converted Dominican church. The books in El Ateneo in Buenos Aires are stacked where plush seats once graced the Teatro Gran Splendid. The Librairie Avant-Gard in Nanjing, named China’s most beautiful bookshop, is housed inside a government car park that was once a bomb shelter.

But a bookstore is more than bricks and mortar, however beautiful. And it isn’t just the fact that books are sold here that makes bookstores such a beacon.

As novelist Ann Patchett confessed before she opened Parnassus Books in Nashville, Tennessee in 2011, “I wanted to go into retail about as much as I wanted to go into the Army.” What she did want was to re-create “the bookish happiness of my childhood.” She’d grown up in Mills bookstore, a 700-square-foot shop where “the people who worked there remembered who you were and what you read, even if you were ten.” Patchett wanted that kind of bookstore— “one that valued books and readers above muffins and adorable plastic watering cans, a store that recognized it could not possibly stock every single book that every single person might be looking for, and so stocked the books the staff had read and liked and could recommend.”

Closing the Loop

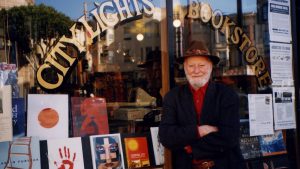

Bookselling is the end of the publishing process, and Ann Patchett isn’t the only writer who has closed the loop between a writer and her readers. In the United States, novelist Emma Straub recently opened Books Are Magic in Brooklyn. Judy Blume owns Books & Books in Key West. Louise Erdrich sells books and Native American art in Birchbark Books in Minneapolis. The most famous American bookstore owned by a writer is probably City Lights in San Francisco, the brainchild of poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Bookselling is the end of the publishing process, and Ann Patchett isn’t the only writer who has closed the loop between a writer and her readers. In the United States, novelist Emma Straub recently opened Books Are Magic in Brooklyn. Judy Blume owns Books & Books in Key West. Louise Erdrich sells books and Native American art in Birchbark Books in Minneapolis. The most famous American bookstore owned by a writer is probably City Lights in San Francisco, the brainchild of poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

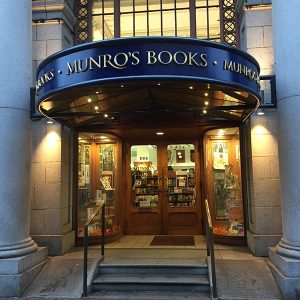

Canada has its own writer-bookseller tradition. In 1963 Jim and Alice Munro—that Alice Munro—opened Munro’s Books in Victoria, BC. Pages on Kensington in Calgary, Alberta, was started by novelist Peter Oliva in 1994. The poet Alice Burdick and children’s author Jo Treggiari are co-owners of Lexicon Books, in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. Last year, novelist Michelle Berry started Hunter Street Books in Peterborough, a university town without an independent bookstore, and this year, Sheree Fitch set up a seasonal bookshop in her granary: Mabel Murple’s Books Shoppe and Dreamery.

Fitch started her shop in response to the threatened closing of the local elementary school. “How can I live here, become part of this community, and turn my back on this?” she said.

Fitch started her shop in response to the threatened closing of the local elementary school. “How can I live here, become part of this community, and turn my back on this?” she said.

Likewise, Michelle Berry’s shop fills a hole left when the only independent bookstore in Peterborough closed in 2012. As one local author put it, “The local lit community was a gang without a clubhouse.”

The Local

Like Zweig’s Mendel, the bookseller makes the book shop—and turns a business into a “local.” Perhaps writers make good booksellers because they know books. They read widely. And the imprint of their taste can be seen on the shelves—qualities shared by all the best bookmen and women.

Like Zweig’s Mendel, the bookseller makes the book shop—and turns a business into a “local.” Perhaps writers make good booksellers because they know books. They read widely. And the imprint of their taste can be seen on the shelves—qualities shared by all the best bookmen and women.

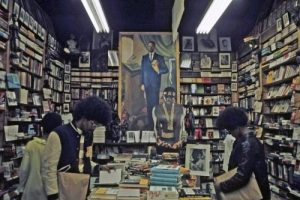

It is hard to parse the precise alchemy by which a bookseller turns a retail business into a vital community hub. Some stores are encyclopedic in  their range of books; others mine a narrow band of literary ore, specializing in psychology, African-American literature, GBLTQ2 books, women’s issues. Some stores set out comfy chairs, an unspoken invitation to sit and contemplate in the company of words. Others offer readings and launches, space where book clubs can meet, workshops convene. In the 1950s and 60s, the National Memorial African Bookstore, nicknamed the “House of Common Sense and the Home of Proper Propaganda,” became the reading room for the American Civil Rights Movement.

their range of books; others mine a narrow band of literary ore, specializing in psychology, African-American literature, GBLTQ2 books, women’s issues. Some stores set out comfy chairs, an unspoken invitation to sit and contemplate in the company of words. Others offer readings and launches, space where book clubs can meet, workshops convene. In the 1950s and 60s, the National Memorial African Bookstore, nicknamed the “House of Common Sense and the Home of Proper Propaganda,” became the reading room for the American Civil Rights Movement.

Convergence

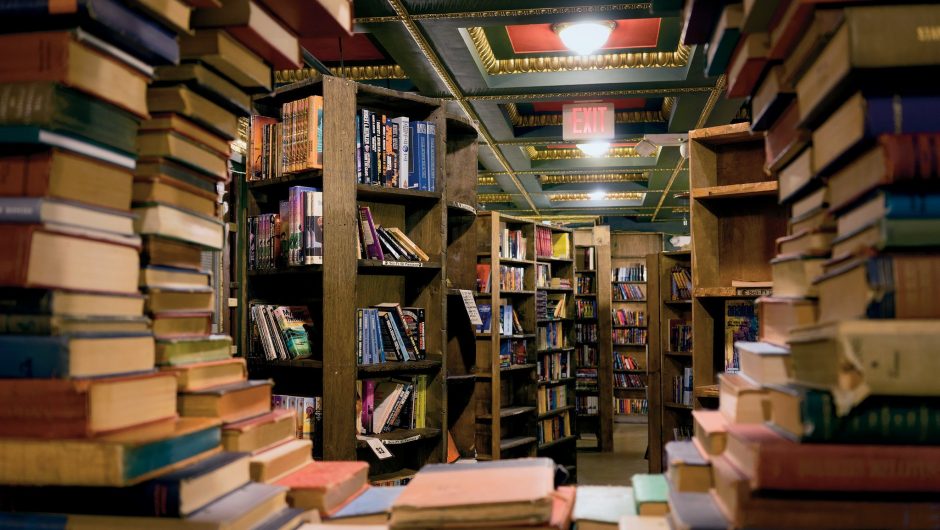

Print-on-Demand may mimic the one-copy-at-a-time bookselling of medieval scribes. Internet booksellers may offer millions of titles at once. Chain bookstores, like 18th-century pedlars, may salt their books with kitchen implements and candles. But it is the independent bookshops that draw us like Mendel’s table in Café Gluck—shops where the shelves reflect the taste of their owners; where the person at the till asks whether your aunt liked that Norwegian mystery you bought her last Christmas; where the staff know exactly the book you mean even though you can’t remember either the title or the author, only that it took place in England and had something to do with a giant, a literary book, but a fantasy, too, sort of; a place where, when you need a serenity break, you can just wander through.

Print-on-Demand may mimic the one-copy-at-a-time bookselling of medieval scribes. Internet booksellers may offer millions of titles at once. Chain bookstores, like 18th-century pedlars, may salt their books with kitchen implements and candles. But it is the independent bookshops that draw us like Mendel’s table in Café Gluck—shops where the shelves reflect the taste of their owners; where the person at the till asks whether your aunt liked that Norwegian mystery you bought her last Christmas; where the staff know exactly the book you mean even though you can’t remember either the title or the author, only that it took place in England and had something to do with a giant, a literary book, but a fantasy, too, sort of; a place where, when you need a serenity break, you can just wander through.

All bookstores sell books, but the best of them are places where writers and readers converge — a local salon where great ideas are exchanged, where conversations are sparked and carried on over months and years, where cultures are spawned and nourished.

“You create books,” concludes the narrator of Zwieg’s story, “to forge links with others even after your own death, thus defending yourself against the inexorable adversary of all life—transience and oblivion.”

And you visit bookshops, I would add, to feel that undying, steadying pulse.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

What is your Best Little Bookshop Ever?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Comments

I don’t remember the name of the bookstore at North Gate in Berkeley, but I vividly remember sitting cross-legged on the floor in the dusty back room, breathlessly combing through their used Nancy Drew titles. Moe’s on Telegraph Ave. was a mecca for historical titles. I would spend hours there, climbing a ladder to reach the high shelves. Black Oak Books was another wonderful Berkeley bookstore. It had formerly been a five & dime when I was in grade school, so I would often think of penny candy whenever I went there.

For me, the sweetest little bookstore ever was Libros El Tecolote in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Mary Marsh, sadly now deceased, was a brilliant selector of titles. I never walked into that store without buying at least one book, and a number of my purchases remain treasures. It’s a bookstore I very much miss.

I remember going into Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and thinking this was so much more than a place that sold books; it was where so many writers have come to feel safe, to speak their minds, and to bathe in the thoughts expressed in the books around them. The store even had a room upstairs for itinerant writers in need of a place to stay.

My favourite bookshop, though, is The Word, in Montreal. Started in 1975 by Adrian King-Edward, it has from the very beginning been a hang-out for writers and readers. Adrian held readings, set books aside he knew a certain customer would want, and published poems and short stories by local writers on what surely must have been the world’s last mimeograph machine. His store became the focal point of Montreal’s English-language writing community. It still is, 42 years later.

My favorite new book store was Pickwick Books in Akron, Ohio. Tucked behind an unassuming mid-century strip mall facade, Pickwick was my paradise. The booksellers were highly educated people who seemingly knew every book in the store. For the owner, it was a labor of love. He held down a second job to help support the staff and store for as long as he could…until Border’s came to town.

This post filled me with nostalgia. I’m in a town with three bookstores and a library at the moment, and am so happy to be surrounded by so many books and the peop who love them.

You know, in another life or in another dimension I would be selling books now. Still I give them away to those who deserve them. I wonder if one day I’ll be giving away my own written books for free or whether I’ll consider getting something in return. Any suggestions?

My favorite bookstore was a Borders, now eaten by Barnes & Noble in Knoxville, Tennessee. It was at the time, a big chain, but in Knoxville it was local with lots of tables and a coffee shop. I was in graduate school and far from home. Everything about Tennessee felt different than Saskatchewan, but a table of books closed the gap and I was myself again. We would wander the aisles and stack up titles on physics and flowers. We would never become experts on either but it was wonderful to spend time with people who were.