When Maya Angelou was eight, a lady took her to the local black school library. The shelves held some 300 books, ragged copies donated from the white school and rebound with shingles covered in pretty cloth. “I want you to read every book,” the lady said.

“I don’t say I understood those books, but I read every book, and each time I would go to the library, I felt safe.”

Maya Angelou told that story at an event celebrating the donation of her papers to the New York Public Library. Then she burst into song:

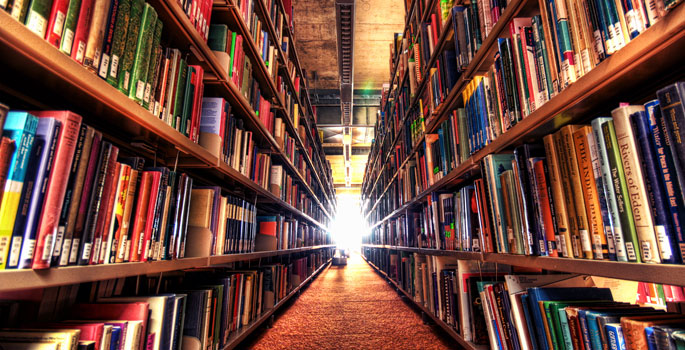

When it looked like the sun would not shine anymore, God put a rainbow in the clouds. Look at that—look at that! That’s a library!—a library is a rainbow in the clouds.

A Rainbow of Books

I went searching for the collective noun for books, hoping it would be something fanciful like a shimmer of hummingbirds or a quiz of teachers, a cloudier of cats. I imagined a puzzling of books, a provocation of novels, a delight of poetry. But no, a gathering of printed pages bound on one side is exactly what one would expect: a library of books.

The word library was coined in the late fourteenth century, after the wholesale copying of manuscripts made collections possible, but before Gutenberg invented his movable-type press.

The word comes from the Old French librairie, meaning a collection of books, which comes from the Latin librarium, meaning a chest containing books—at the time, about as many books as even a rich person was likely to own.

A Destruction of Books

Gathering books into one place makes them vulnerable. The most famous ancient book-hoard, the library at Alexandria, accidentally burned to the ground during the Siege of Alexandria in 48 BCE, when a fire set by Julius Caesar’s troops spread from the docks into the city. Other book bonfires were intentional: in 1499, the Inquisition seared eight centuries of Islamic culture and 13 centuries of Jewish culture in Spain. In 1562, eight centuries of Mayan literature was consigned to flames. When Baghdad’s National Library went up in smoke in 2003, some of the earliest Arabic and Persian writing was reduced to ashes. The first written fables, the first stories, the first laws disappeared as clay tablets were pillaged and smashed.

By some estimates, 99 percent of ancient Greek literature has been lost through fire, war, and the whims of history. Of the nine volumes of verse written by the Greek poet Sappho, only one complete poem survives. Of Livy’s 142 books on the history of Rome, only 35 can still be read today. Ovid’s version of Medea, Gorgias’ philosophical On Non-Existence, 74 plays by Euripides, some 90 plays each by Aeschylus and Sophocles, the entire works of the Greek philosopher Epicurus—all gone. And these are just the books that we know are missing because we’ve found some reference to them. Conflagrations of one sort or another must have destroyed hundreds of thousands of books we’ve never heard of—and never will.

An Alphabet of Books

When I visited the Roderick Haig-Brown House in Campbell River, British Columbia, I received strict instructions about using the writer’s library. I was not to touch a book without first slipping on a pair of the white cotton gloves mounded in a basket on the coffee table.

The books in that library are arranged not alphabetically by author or by title, but according to the birth date of the author. This boggled my mind, especially given that the system was developed in pre-digital days when it wasn’t easy to discover when a writer was born.

I’ve seen personal libraries shelved according to the height of the books or the colour of the spines. The main character in Nick Hornby’s novel High Fidelity organizes his record collection autobiographically, according to the day each was acquired. In Canada, public libraries use the Dewey Decimal System to shelve books alphabetically by author within numbered subject categories. The Library of Congress divides knowledge into 20 classes, represented by capital letters. B is Philosophy, F is History, P is Literature. Only G for Geography makes any kind of sense.

In our country house, we organized our books by room. The dining room was Canadian fiction, my study was international fiction, the hallway was sociology and history, the kitchen was culinary, and the third floor was science and nature. Within each category, books were shelved alphabetically by author. A few years ago, when we suffered a renovation disaster, cleaners in hazmat suits took down each of our 10,000 books, cleaned it of silica dust, and packed it into a box, returning it to the shelf once the house was cleaned. We took pains—in vain, it turned out—to explain the importance of not only having books, but being able to find them.

A Byte of Books

Maybe it’s the ephemeral nature of thought that makes us so intent on arranging and storing written words. Project Gutenberg, for instance, takes as its mission the archiving of all the great cultural works of the entire world. The first books were entered manually into computer files by volunteers at Benedictine University. Since optical character recognition scanners, books are added at a rate of about 50 a week. Over 50,000 titles are now available through the Project Gutenberg website. Google Books Library Project has digitized some 30 million.

Does this make a public library with shelves of paper books dispensible? Governments, the usual overseers of public libraries, occasionally think so. Only major demonstrations convinced Rob Ford not to make drastic budget cuts to Toronto’s public libraries, and in Newfoundland, forced the powers-that-be to abandon plans to close 54 rural libraries.

“All information belongs to everybody all the time,” Maya Angelou said that day in the New York Public Library. “Information helps you see that you’re not alone. That there’s somebody in Mississippi and somebody in Tokyo who all have wept, who’ve all longed and lost, who’ve all been happy. . .the library helps you see not only that you are not alone, but you’re not really any different from everyone else.”

A Body of Books

At the time of her death, Maya Angelou had a personal library of more than ten times the number of books in that first black school library.

I watch my friends carting their books to the Salvation Army, to the Symphony Sale, to the curb, and I wonder: is the home library in danger, too? I admit that I have been tempted to clear our bookshelves in favour of an electronic library—my own and the ones I subscribe to.

But I would miss browsing. Not the scattered hunt-and-peck of a Chrome search, the kind that strains the eyes and exhausts the brain. I would miss the browsing I do when I stand and stare at my wall of books. Browsing that is something like daydreaming: an unleashing of the brain to wander where it will, making connections unguided by the rational mind, scanning past Homes, Hoeg, Ishiguro, Kingsolver, and in the muddling of those works, coming up with an idea for an altogether new kind of literary cocktail.

My library—my books—are my brain and my heart made visible.

When I first visited a library, I was somewhat younger than Maya Angelou. With my mother, I climbed the stairs to the room above the firehall where she worked as a volunteer once a week, managing the few hundred donated books on the shelves. I, too, felt safe in a library. I still do.

2 Comments

When I was seven our local was a place of discovery and a new language. We lived in an English-mainly town in Marine (so the library had mainly English books). We spoke French only at home, school,. church and friend’s homes. My university-educated parents could speak English very well but were determined that we become bilingual. The library was where I discovered English, except for some street English picked up here and there. The library was English land–a place of magic and discovery. When I was old enough at about seven I went by myself. i asked for Trixie Belden . The librarian would not give it to mr (‘your grandmother will kill me”) . So she gave me Austen and Dickens and the poets Dickenson and Keats…….And that is how a young girl who had yet to be taught how to

read English first learned English –visually not aurally–(with parental help when I got stuck. I agree with the English writer Newman that the best education (language included) is to let someone randomly loose in a library — random is magic.

My earliest library memories are of the Bookmobile that used to come to our two-room, rural school once a week. Books lined both sides of the former yellow school bus, and I vividly remember drifting down one side and up the other, running my fingers along the titles — mostly written in white ink on black tape — and choosing the two we were allowed each week. The first book I remember reading on my own was The Adventures of Pinocchio, but I know I read many others because I kept a list, and by the end of the year the list was nearly fifty books long. I can still feel the ridges where the type was pressed into the pages, and smell that indescribable scent of a cloth-covered book that has been read so often the pages are as soft as chamois. I wish I could say I graduated to Austen and Dickens, but I don’t remember reading those authors until much later — and I doubt they were in the Bookmobile, anyway. The Bookmobile may not have hooked me on great literature, but it certainly addicted me to books.