[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] People often say that writing a book must be like having a baby, to which I respond, “I wish it only took nine months!” Writing may not be like childbirth, but producing a book is. The minute the physical object is in your hands, the hard parts are forgotten.

Gutenberg’s Fingerprint tells the story of the making of The Paradise Project, my collection of flash fiction, as both an electronic book and as a limited edition letterpress book, hand-printed on an antique press by Hugh Barclay at Thee Hellbox Press. The memoir is due out in April; it’s only been three months since the pages were proofed and the book put to bed, but already I look back on the grubby print shop, where we lurched joyously from one near-disaster to the next, with a fondness I recognize in Rita Dove’s memoir about the making of her letterpress book of poetry.

Gutenberg’s Fingerprint tells the story of the making of The Paradise Project, my collection of flash fiction, as both an electronic book and as a limited edition letterpress book, hand-printed on an antique press by Hugh Barclay at Thee Hellbox Press. The memoir is due out in April; it’s only been three months since the pages were proofed and the book put to bed, but already I look back on the grubby print shop, where we lurched joyously from one near-disaster to the next, with a fondness I recognize in Rita Dove’s memoir about the making of her letterpress book of poetry.

“I love the world of the print shop,” the American Poet Laureate writes in her essay “The House that Jill Built” in Life Notes: Personal Writings by Contemporary Black Women. “There is a calm and order, an adagio sense of time that permits the appreciation, the heft, of each detail—the positioning of a comma, the measured appraisal of every letter and space, the sheer physical investment of setting a page of type. Isn’t this how every writer imagines writing, setting down each letter with deliberate care, setting it to last, tamping it in?”

The Hidden Language of Books

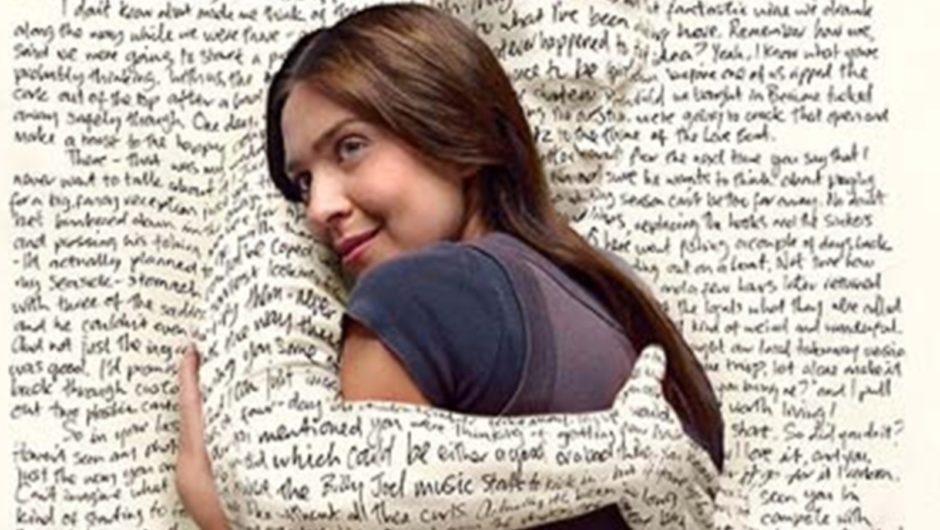

The nostalgia I feel for the Hellbox production of The Paradise Project is part of how I feel about all books. I love books. An irrational, deep, elated, sometimes enraged love. I cannot imagine my world stripped of printed books. And I’m not alone. Something about printed books elicits strong emotion. People refer to them as friends, as companions, as the scripted playlist to their lives. This may be because language provokes emotions that attach to the sensory cues so important to our memory-storage process. But that doesn’t explain why, for so many, printed books are such beloved icons.

Clearly, books are more than plot, more than characters, more than facts and ideas.

In novels, books are often used as a kind of short-hand to signal that a character is educated, enlightened, worldly. The books that line the rooms in Alan Paton’s Cry, The Beloved Country spell emancipation. In Fahrenheit 451, they symbolize freedom of thought and will, everything a fascist society is not. In The Book Thief, books are identity, immortality, an emblem of hope.

Books as Brand

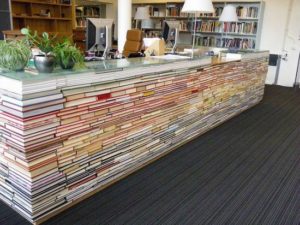

But what does it mean when books are used as decoration, as decor, as art?

Restauranteurs buy books by the yard to paper the walls of their cosy pubs and bistros. Books have been glued together to make bed frames, couches, chairs, even an outdoor bench in Berlin, where the books are renewed each season. In Sweden, a floor-to-ceiling partition was made out of books laid flat, end to end, like thin bricks. An Australian bookseller made his check-out counter entirely from books. A British company makes chandeliers from the fanned pages of old books.

I’ve seen books reamed out to hold flasks, secret documents, and house keys. At the Grimsby Wayzgoose this year, an artisan printer was selling teensy books to wear as necklaces. I can wear actual pages from Pride and Prejudice pasted over a big wooden bead. Or a pendant made of a glass bottle containing a tiny page printed with text from Wuthering Heights. Or a brooch in the shape of a bird covered with a varnished “original page from damaged copies of Harper Lee’s classic” To Kill a Mockingbird.

Orphan Pages

Copying quotations and creating likenesses of books is one thing. But a few years ago, a gift shop near where I live put two mannequins in its window, one wearing a very swish suit and the other an elegant cocktail dress, both made from pages of books by Ovid and Noel Coward.

I am a recycler at heart, but even so, the sight of those orphaned pages made me queasy. This repurposing of actual pages of actual printed books struck me sacrilege until one morning I looked over at the framed picture on the wall by my bed. It is a page from the nineteenth century book, The Language of Flowers, showing an early lithograph of roses, violets, and tulips. Brought together in a bouquet, the flowers say, “Your beauty and modesty have forced from me a declaration of love.”

A razor-bladed book page had been staring me in the face every morning for twenty years, and I’d only just noticed.

A Candle Named Book

At one time, Amazon sold a candle called New Book that promised a scent reminiscent of the unique smell of a freshly opened book. They described the fragrance as “an unabridged blend of lignin, ambered glue, and fresh India ink, narrated charmingly with white ginger and sweet pine resin.” There are “old book” and “paperback” perfumes, too.

People must be buying this bookish paraphernalia. Otherwise, it would not appear on the digital and physical shelves. Clearly, people not only want to read books, they still want the smell, the touch, the sight of them close at hand.

And what does all this say about the place of the paper book in our culture?

Maybe it means that such books are on the way out, that we are clutching at the last shreds of loose pages and phantom smells.

Or maybe it says that the brand is still fresh. That books—the idea of books and the physical thingness of books—have been set to last.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

Have you ever used a book for something besides reading?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Comments

A few years ago, I discovered a hard lump under the skin of my right hand, about the size of a pea. It was slightly above the knuckle of my index finger: if I were a snuff-taker, it would have been just in that hollow between the back of my hand and my thumb where the snuff would be. I ignored it for a time, sort of, but when I went to my doctor’s for some other unrelated reason, I mentioned this accretion to her. She looked at it carefully, rolled it around under her finger for a time, frowned. and said, “Some kind of protein accretion, it seems.” She stood up and, going to her bookshelf, removed a large, heavy tome and brought it over to the table. I assumed she was going to open the book to look up my condition. Instead, she had me put my hand flat on her desk. She then placed the heavy book on top of my hand, just over the accretion, and then brought her fist down hard on the book. “That should do it,” she said, and sure enough, when she took the book away, the lump was gone.

This post beautifully encapsulates the profound impact literature can have on our lives. It’s a reminder that books are not just ink on pages; they are gateways to new worlds, sources of solace, and catalysts for personal growth. They have the power to touch our souls, inspire us, and even change the course of our lives. Your words resonate with every book lover out there and serve as a testament to the enduring magic of storytelling. Thank you for this eloquent ode to the written word, reminding us that sometimes, a book is a cherished companion on life’s journey.