[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] 2017 is the 40th anniversary of the personal computer and the 25th anniversary of the first ereader. A quarter century and millions of ebooks later, writers and readers, friends and pundits are still arguing over whether this is a good way to read books.

The first prototype ereader—a floppy-disk-driven, six-inch device called Incipit—was developed at the University of Milan in the early 1990s. But it wasn’t until 1998 that two ereaders—SoftBook and the Rocket eBook Reader—were introduced, along with websites where ebooks could be downloaded for a fee. The Millennium and the EveryBook came out in ’99; the Cybook launched in 2001. Who remembers any of these?

Those first ereaders weren’t very different in principle from Kindles, Kobos, and their ilk except for storage capacity (limited to 1,500 pages or about five books) and Internet connectivity, which was so dicey that all but the most intrepid early adopters gave up.

The Readies

Ereaders may not have been invented until the 1990s, but the idea was articulated just under a century ago in an essay called “The Readies” by Bob Brown, which appeared in the journal transition. In 1930, after watching a “talkie” (movie), he got the idea that books, too, needed a shot in the arm, “a machine that will allow us to keep up with the vast volume of print available today and be optically pleasing.”

Brown wasn’t an inventor, so nothing came of his idea, but he was prescient in his prediction that such a machine would allow users to adjust the type size, avoid paper cuts, and save trees.

Beam the Book Down, Scottie

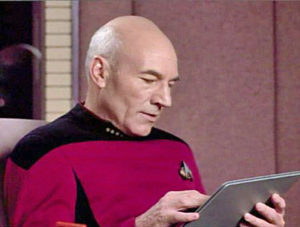

I saw ereaders long before I could buy one. I was a Trekkie. Through the late 1980s and early 1990s, Star Trek: The Next Generation was my eye-candy of choice, a television series that based its plots on the works of Raymond Chandler, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, William Shakespeare, and even Gilgamesh, while showcasing fantasized, twenty-fourth century technology.

At quiet moments, Captain Jean-Luc Picard would retire to his cabin with a cup of “Tea—Earl Grey—hot!” and a book, sometimes an antique twentieth century paper book, but more often a small rectangle that he held before him like a mirror, reading pages that scrolled before his eyes. Magic!

Riding the Bullet

Despite the advance prep of Star Trek, the first ereaders provoked the virulent love-hate reaction that so often greets a new technology. Some writers jumped on the bandwagon: Stephen King’s novel Riding the Bullet, released in 2000, appeared first as an ebook.

Within five years, however, the limited memory and download irritations cancelled out the geeky novelty of the reading device. By 2003, ereader manufacturers were going out of business and Barnes & Noble was closing down its ebook sales division.

“Ha!” print-lovers gloated. “A flash in the pan!”

Their triumph was short-lived. Just one year later, Sony released LIBRIé, the first ereader to use electronic-ink technology. Finally, words on the screen had almost the same clarity as words printed on paper. In 2007, Amazon introduced the Kindle, connected to Whispernet, their private data storage and retrieval system that held millions of books, an avid reader’s wet dream.

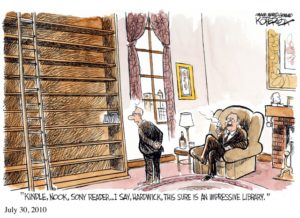

The Kindle and the ereaders that followed—The Nook (Barnes & Noble), Kobo (Chapters/Indigo) and the Sony Reader—are all dedicated ereaders. They don’t run email or Facebook or any other distracting applications. They are just books: super-thin, spineless, coverless books that, like paper books, are content to sit patiently on a shelf, waiting to be picked up and flicked open/on. They exist only to be read.

The Kindle and the ereaders that followed—The Nook (Barnes & Noble), Kobo (Chapters/Indigo) and the Sony Reader—are all dedicated ereaders. They don’t run email or Facebook or any other distracting applications. They are just books: super-thin, spineless, coverless books that, like paper books, are content to sit patiently on a shelf, waiting to be picked up and flicked open/on. They exist only to be read.

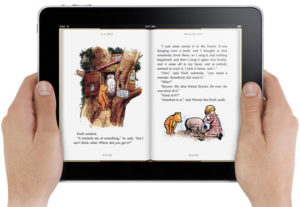

When Apple introduced the first iPad tablet in 2010, I was at the sales counter. It was bigger than a cellphone or any dedicated ereader and had a better screen. The iPad came with a built-in app called iBooks, but I could also download Kindle and Overdrive and Kobo. Since then, tablets have proliferated and no wonder: they unchain us from a single mega-retailer monopoly. We can buy stories from iTunes, novels from Amazon, download a nineteenth-century novel from Project Gutenberg, share EPUB files of our self-published ebooks.

My Kindle languishes on the shelf. I can’t give it away. I’ve tried.

The Half-Life of Techno-Lust

By 2014, fully half of all American adults had an ebook reading device, either an ereader or a tablet. (Forty-five percent had tablets, nineteen percent owned ereaders, some owned both.)

But here’s the thing: although half of American adults owned an ereader, only twenty-eight percent claimed to have read an ebook. Is this just another case of techno-lust? In a few years, will people be tossing their ereaders into the same box in the basement that holds their Game Boy, their Discman, and their eight-track tapes?

Ereaders, dedicated or not, are almost certainly a transitional technology. We’ll look back on the so-called state-of-the-art digital technology we’re using today and see these ereaders as Model Ts compared to how we’lll be reading in twenty, ten, or even two years.

Ereaders, dedicated or not, are almost certainly a transitional technology. We’ll look back on the so-called state-of-the-art digital technology we’re using today and see these ereaders as Model Ts compared to how we’lll be reading in twenty, ten, or even two years.

Ereaders may be like television: astonishing when it came into my living room in 1956, essential through the moon landings, assassinations, famines, wars, and Dr. Whos of the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, and first two decades of the new millennium, then suddenly obsolete, replaced by Internet streaming. Who knew we would abandon that technology so completely, with hardly a backward glance?

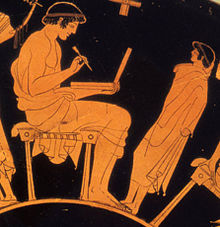

Scrolling Backwards

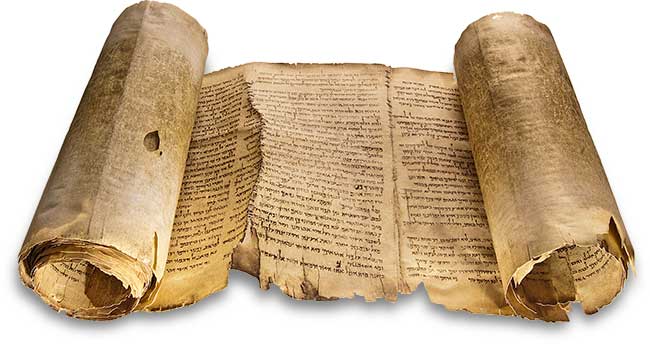

The paper book was invented in the first century CE. Scrolls were so cumbersome, the Romans developed hinged wooden tablets smoothed with wax—an early version of Etch A Sketch—to scratch a few notes. Because the paper book was descended from these erasable tablets, it was dismissed at first as transient, appropriate only for passing thoughts.

What we forget is that the paper book and the scroll co-existed for several hundred years. The codex slowly gained in popularity until, by 300 CE, the two “display technologies” were equally in use. After that, the scroll gradually fell from favour, disappearing except for religious and ceremonial use by 1000 CE.

From tablets and scrolls to scrolling tablets, and in between, the codex we call book. Each greeted with suspicion. Each embraced, eventually, as a godsend. Each expected to survive forever. Each of them giving way, inevitably, to the next best thing.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

Has the way you read—the display technology you use—changed over the last few years?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Comments

Wonderful post!

I bought one of the early e-readers for my mother-in-law because she was loosing her sight. It was clunky, but she was delighted by its ability to greatly increase text size. Plus, she became something of a tech star in her nursing home.

I find that I’m now reading in all forms.

I prefer to read a novel in print — especially a literary novel that requires some thoughtful flipping of the pages. What’s to replace the tactile swoon that comes at the end of a wonderful novel, holding the book to your heart in wonder? And what’s to replace the impulse to share? “I think you will love this book!”

That said, the first novel I read digitally was A Reliable Wife by Robert Goolrick, which I read entirely on my little iPhone. The enchantment of that amazing novel is with me still. Enchantment, I discovered, was not restricted to any one media.

I can no longer read a novel in small type. These I prefer to read on an e-reader with the type blown up to a comfortable level. I am currently very much enjoying switching back and forth between the audible and Kindle editions of Middlemarch. (Audible editions! Yet another form of enchantment!) A friend plans to read Middlemarch on her Kobo, but with the print edition close at hand, for reference.

For non-fiction, I appreciate being able to highlight passages in a digital edition, passages that I can then send to an on-line database (Evernote, in my case) for future use.

I love all forms, and for different reasons. What’s next? I can’t help but wonder.

My trajectory is similar, Sandra. I love the sound, feel, smell, heft of paper, but in Mexico, where there are no English-language new bookstores, I read mostly in digital formats. My phone remains a new frontier!

I enjoyed this posting very much, as much as I have found all the previous ones interesting and informative. Because of variable eyesight I was forced to read it on my laptop instead of my Ipad Mini, which refused to enlarge the type. Would it be possible to increase the font size of the blog a bit for those of us who are no longer Spring chickens?

Please keep up the good work, Merilyn, and enjoy the sunshine for all of us.

Jean Gower

I’m sympathetic! I’ll check with my design guru. As a last resort, you can copy and paste into a Word file and bump it up as big as a billboard! I do that for some of the books I read on my iPad.

How do you do these amazing posts, Merilyin?!! This is quite incredible.

Thank you! I love books—holding them, reading them, writing them, thinking about them in all their forms!