[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Most of my day is spent in front of a computer screen. I read thousands of words between dawn and dusk. But when I say to my husband, “I’m going to read now,” he knows what I mean. I’m leaving him for a book.

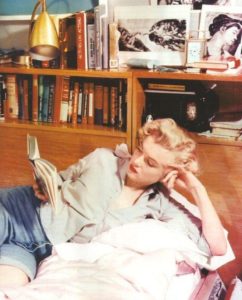

I prepare for my dalliance with anticipation and care: a warm drink, maybe chocolates, the chair fluffed with cushions, the lights just so, the door closed.

There is something deeply intimate about a book. It nestles in my hands for hours, my fingers tracing down its spine. I gaze into its pages with rapt attention. My husband, bless him, isn’t jealous. We have an agreement: I sit up with my books; he takes his to bed.

Books repay our devotion with constancy. The words are always there. They wait for us to come back to them, to read them again, next week, next year, half a century from now. The patience of books is infinite, but they are not passive. They draw us in, sharing their complexities, making their arguments, exposing their heart. Insistent and persistent, they urge us to listen, to let go, to put our mundane worries aside and give ourselves up their words. To crawl out of our own skins and into theirs.

Books repay our devotion with constancy. The words are always there. They wait for us to come back to them, to read them again, next week, next year, half a century from now. The patience of books is infinite, but they are not passive. They draw us in, sharing their complexities, making their arguments, exposing their heart. Insistent and persistent, they urge us to listen, to let go, to put our mundane worries aside and give ourselves up their words. To crawl out of our own skins and into theirs.

What a relief! Books invite me to hear something besides my own thoughts. I am free to disagree, but I can’t change what a book is saying. It’s still there, uninterrupted, making its case every time I turn to it. I can despise it or love it, it hardly matters. In the end, I have to accept it for what it is.

I don’t care what my book is made of or what it looks like. It’s what’s inside that counts. A good book can change my life.

An Intimate Weight

“I loved the warm spot caused by their intimate weight in my lap; the musky odor of old paper and the sharp inky whiff of new pages. I loved to gaze at a closed book and daydream about the possibilities.”

Rita Dove understands. In her essay, “For the Love of Books” the former Poet Laureate Consultant of Poetry to the Library of Congress admits to succumbing to the allure of books at an early age. We are both, it seems, promiscuous.

There’s a word for this, of course. (There’s a word for everything.) Bibliophilia: from philia (love) and biblio (books).

There’s a word for this, of course. (There’s a word for everything.) Bibliophilia: from philia (love) and biblio (books).

Bibliophiles don’t necessarily need to own the books they love, but they never want to be without them. Bibliomaniacs, on the other hand, feel compelled to possess, even it means losing friends, family, fortune.

How odd that the Library of Congress refers to book-lovers as either collectors or bibliomaniacs, refusing the lovely bibiophilia, which makes me think of being carried off by a young filly into strange and wonderful landscapes, muscles rippling under my thighs.

A Body Without a Soul

Although the word is only 200 years old, bibliophilia in the form of book-collecting goes back to the Romans. In A Gentle Madness: Bibliophiles, Bibliomanes, and the Eternal Passion for Books, Nicholas Basbanes tells us that Cicero, who lived in the first century BCE, had personal libraries in all his country estates as well as in his villa in the centre of Rome. Vitruvius, a Roman architect of the time, remarked that, like hot and cold baths, a library was “a necessary ornament to a great house.”

But for Cicero, books were more than architectural embellishment.

“A room without books,” he wrote, “is a body without a soul.”

Is a Bookshelf Without Books Still a Bookshelf?

Is a Bookshelf Without Books Still a Bookshelf?

As long as there have been books, there have been shelves to hold them close. The earliest were in the ancient library at Ebla, one of Syria’s first kingdoms, southwest of the modern, beleaguered city of Aleppo. Ebla’s library consisted of a series of small, almost square rooms with floor-to-ceiling wooden shelves for the clay tablets, each one facing out. The Romans carried on the tradition, keeping scroll written in different languages in different rooms.

Cicero enlisted Tyrannio, an educated Greek slave, to build new shelves and put his library in order. “Now that Tyrannio has arranged my books,” he wrote, “a new spirit has been infused into my house.”

But how did Tyrannio arrange the books? I’m dying to know.

Delicious Library

A few years ago, my husband and I spent a weekend taking books off the shelf to scan them into Delicious Library, the Mac app that digitally catalogues private hoards of books. We soon gave up. How on earth could we scan every one of our 10,000 books? It would be like listing every bone in our bodies. Worse: like cataloguing friends and lovers.

I can’t imagine defacing all those lovely spines with stickers, not even colour-coded ones without numbers. For a while we tried subject labels on the shelves but they curled and stained the lovely maplewood.

I can’t imagine defacing all those lovely spines with stickers, not even colour-coded ones without numbers. For a while we tried subject labels on the shelves but they curled and stained the lovely maplewood.

Nassim Taleb, the Lebanese-American essayist and thinker who makes a specialty of randomness and uncertainty, describes the human inclination toward organization: “We humans, facing limits of knowledge and things we do not observe, the unseen and the unknown, resolve the tension by squeezing life and the world into crisp commoditized ideas.”

No map, he suggests, is better than the wrong map.

The Rule of Good Neighbours

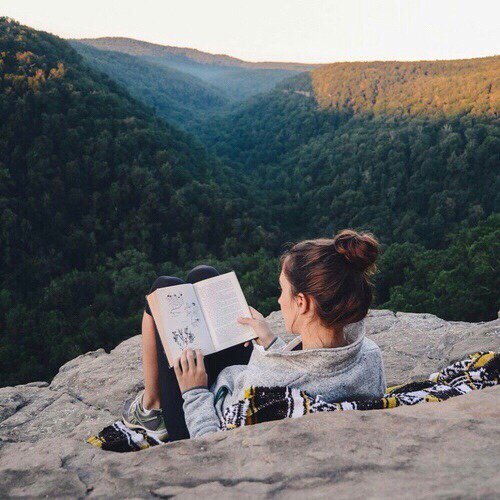

Loving books means making a home for them, a comfortable place to rest until you are ready to let them change your life again.

Aby Warburg, the Austrian art historian, anthropologist, and linguist, developed a system of book-shelving he called “the rule of good neighbours.” It is still used to organise the books at the Aby Warburg Institute in London, England. When the first books arrived at their new home, Warburg gathered the staff together and told them:

“My library must follow the order I have for it in my mind, and therefore the volumes will be rearranged according to my directions. And common sense and functionality be damned!”

“My library must follow the order I have for it in my mind, and therefore the volumes will be rearranged according to my directions. And common sense and functionality be damned!”

My friend’s father chose the same system. Over his lifetime, he collected 60,000 books, which he shelved in his house and in his office. When he died, all the books were shipped to a two-storey house built specifically to house them in the small village where he had planned to retire. The house is furnished with bookshelves, squishy chairs and couches, and a wood stove for winter. A sign by the perpetually unlocked front door asks readers to leave their electronic devices in the bowl by the entrance and to enjoy the books within the reading room, returning them to the shelves for the pleasure of others.

As in the Warburg Institute, the books here are shelved not by genre or alphabet but by their connections to one another, because that’s how the brain works, this book-collector said. He believed it was more conducive to the positive power of books and reading if you could look at a book on a shelf and draw your own connections between it and the books on either side—connections within yourself and within the room.

I imagine settling into that reading room, working my way slowly through the shelves, paying attention to the neighbours, letting each book have its way with me. [vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

What book has changed your life? Where does it live? Where did you read it?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

CONTEST! Tell us about a great book that changed your life and win 1 of 4 ARCs of Gutenberg’s Fingerprint from the publisher. (These unfinished galleys will soon be collectors’ items, they tell me.) Everyone who enters a comment in this week’s blog, or on the Facebook or Twitter posts—using the hashtag #GutenbergsRelease— is automatically entered to win. The Contest closes Friday evening, February 17.

6 Comments

Lovely! What a treat to read your blog in the middle of a busy, wintry morning. Next week is Reading Week here at the university where I work (although they’ve given up on the name Reading Week and now call it Winter Break). I’ve got a stack of reading at the ready for the hopefully-quiet week ahead. Mostly PhD theses and a book to review, but I’ll slip in one fun book as well.

Maybe they are reading as they ski?

#GutenbergsRelease It may sound strange, but it was Beatrix Potter’s A Tale of Two Bad Mice. The first book I ever bought with my own money, and it set me on a path of lifelong love of well-made books and of reading.

The first book on my shelf (given to me the day I was born by my aunt who died last week in her 100th year) is a Beatrix Potter. I wish I could remember the first book I bought with my own money!

Wonderful post, Merilyn!

My passion for Nancy Drew one summer lured me to scour used bookstores for her titles. I remember sitting cross-legged at the back of a musty bookstore, hungrily looking for a Nancy Drew title on the bottom shelf.

In high school, we were assigned Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell, a book that triggered a fever in me that has yet to abate!

Another book that stands out for me was A Walk With Love and Death by Hans Koningsberger (now Koning), which I read at 17. It’s a slim, spare historical novel set in 14th Century France. It was very hard to find then — this was well before AbeBooks.com — so I special requested it from a library and had a photocopy made. I couldn’t bear to be without it! After I became a writer of historical fiction, I wrote to Hans Koning to let him know how much his novel meant to me, only to be informed by his family that he’d died shortly before. (Ahhhh!) It’s one of the few books I’ve read several times over and I think it’s time that I reread it yet again.

Oh, so many satisfying hours sitting cross-legged on musty library floors. Until I had my own library, that’s where I was happiest, hidden between towering bookshelves, escaping in body, mind, and heart from the so-called real world into those endless worlds of the imagination. I say this, having spent the entire night on the couch, under a warm afghan, engrossed in The Book of Lamentations by Rosario Castellanos.