[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]My husband hears draft and thinks beer. I hear draft and think breeze. We’re both writers, but when it comes to producing drafts (not beer or breezes but the scribbling kind) we are as different as two writers can be. Ask him how many drafts it takes to write a book, and he’s likely to say, “Six or eight.” I’ve never racked up fewer than fifteen. I thought my new book would be different, but here I am at ten, and my agent has just spoken those dreaded words: “It’s not ready yet.”

What is a draft anyway?

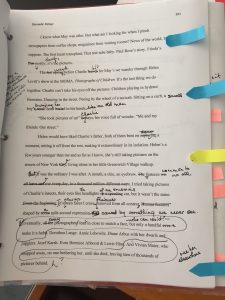

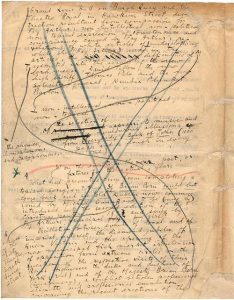

Before computers, drafts were easy to define. I’d type a manuscript, work it over with a blue, red, or lead pencil, or maybe a fountain pen (unwise, given the flood in my future). When the pages could no longer be read for all the cross-outs and add-ins, when the cut-and-paste became more a maze than orderly signposts of change, I’d retype the manuscript and presto! a new draft.

Before computers, drafts were easy to define. I’d type a manuscript, work it over with a blue, red, or lead pencil, or maybe a fountain pen (unwise, given the flood in my future). When the pages could no longer be read for all the cross-outs and add-ins, when the cut-and-paste became more a maze than orderly signposts of change, I’d retype the manuscript and presto! a new draft.

Now when I ask my husband what draft he’s on with the new novel, he looks puzzled. “Hard to say. Five? I keep changing things between print-outs.”

Puke, Shit, and the Kitchen Sink

I don’t count my first draft in my numbering. This is the lay-down draft. The puke draft, as my husband likes to say. What Calvin Trillin calls his vomit draft. Others call it the kitchen-sink draft because everything goes in. John McPhee compares it to flinging mud at the wall.

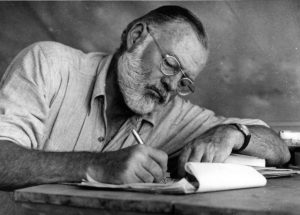

Or as Hemingway famously and concisely put it, “The first draft of anything is shit.”

Or as Hemingway famously and concisely put it, “The first draft of anything is shit.”

I like to think of this first foray as my donné draft. A gift. Everything that comes into my mind goes onto the page: thoughts, scenes, snippets of dialogue, flashes of description. I write my donné draft longhand, the movement of my arm a gleaner’s gathering from my subconscious. I write only on the right-hand side of the page, flipping back to jot quick notes on the left side. Raúl should appear here. Get Amanda to Chiapas before now.

The donné draft is never complete. It rarely has a beginning, middle, or end. But the main characters are born and the outer boundaries of this world staked out, even if I don’t know yet exactly how I’ll lead the reader through.

The Affirmation Draft

The first draft is the one that tells me this may indeed be a book. By the time I finish the affirmation draft, the story has a beginning, middle, and end, although not necessarily in that order. I know my protagonist the way I know a good friend or a bad enemy: I know what she wants and what she needs and what sparks fly between the two. The possibilities send a shiver of delight across my skin, a flash of power that must be what the gods felt at the end of the first day.

The first draft is the one that tells me this may indeed be a book. By the time I finish the affirmation draft, the story has a beginning, middle, and end, although not necessarily in that order. I know my protagonist the way I know a good friend or a bad enemy: I know what she wants and what she needs and what sparks fly between the two. The possibilities send a shiver of delight across my skin, a flash of power that must be what the gods felt at the end of the first day.

As an antidote, I turn to Bernard Malamud’s words to a graduating class at Bennington College: “The first draft of anything is suspect unless one is a genius.”

I’ve been at this way too long to think I’m a prodigy.

The Magpie Draft

I call my second draft my magpie draft, as the manuscript plumps with all the shiny bits I find.

I call my second draft my magpie draft, as the manuscript plumps with all the shiny bits I find.

I research in books and on the Internet. I scrabble about in my memory. I walk the streets, picking up a gesture here, a swatch of wall there. Often I have no idea how a piece might fit but I shove it in anyway. I tell myself I can always jerk it out.

I give myself up to the process, which feels incoherent and dangerous, but exhilarates me.

Campdrafting

Australians have devised a sport called campdrafting, in which a person on horseback has to cut a steer from the herd and block and turn the animal several times to prove they are in control.

Australians have devised a sport called campdrafting, in which a person on horseback has to cut a steer from the herd and block and turn the animal several times to prove they are in control.

Writers play a similar game, variously called “Rearranging the Furniture” and “Killing your Darlings.”

The drafts that follow the Affirmation and the Magpie are messy. They require great focus and ruthlessness, and more than a few long dark nights of the soul. The work is sometimes boring, often discouraging, and different for every writer. But neither experience nor reputation gives a writer a pass on multiple drafts.

“Revision is the constant creation of afterthoughts,” Malamud said. “One learns the best way to milk one’s mind.”

Laboriously, I pull bits out, tighten things up. Maybe the story doesn’t need that ragged swatch of red: maybe a scarlet thread will do.

Thrashing about in the desert of these middle drafts, I lose faith. I worry that I lack what it takes to pull this story together. It’s too big for my puny skills, too complex. I’m not the right god to create this world.

I take comfort from others who have wandered this writerly wilderness before me. Hemingway, by his own count, rewrote A Farewell to Arms at least fifty times. In Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov admitted, “I have rewritten — often several times — every word I have ever published. My pencils outlast their erasers.” Dorothy Parker once said in an interview in The Paris Review: “I can’t write five words but that I can change seven.”

I take comfort from others who have wandered this writerly wilderness before me. Hemingway, by his own count, rewrote A Farewell to Arms at least fifty times. In Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov admitted, “I have rewritten — often several times — every word I have ever published. My pencils outlast their erasers.” Dorothy Parker once said in an interview in The Paris Review: “I can’t write five words but that I can change seven.”

“Put down everything that comes into your head and you’re a writer,” Colette wrote in Casual Chance. ”But an author is one who can judge his own stuff’s worth, without pity, and destroy most of it.”

The Ah-ha! Draft

Then suddenly, ruthlessly, doggedly, a draft comes along that doesn’t seem so bad. In fact, it’s pretty good. Damn good! I dance to the rhythm of the words, the harmonies that weave and cascade and soar to a crescendo. I fall in love again.

Then suddenly, ruthlessly, doggedly, a draft comes along that doesn’t seem so bad. In fact, it’s pretty good. Damn good! I dance to the rhythm of the words, the harmonies that weave and cascade and soar to a crescendo. I fall in love again.

Yes, the scaffolding still has to be removed: all those dialogue tags and characters descriptors and narrative directions that helped me find my way through the story, but which a reader doesn’t need at all.

By now my book-world is fully formed and well-populated. I’ve structured a clear path to lead the reader from first page to last. All that’s left is to free the path of impediments. With the dedication of a Japanese gardener, I rake away the boulders of over-description, the rocks of cliché and jargon, and infelicitous phrases. With each raking, I expose a new crop of obstacles, but smaller ones, easily removed, until the path is a smooth white swath in the moonlight.

Oh, how I strain for metaphors to describe this painful business, this drudgery that writing becomes, the uncertainty of it, the mysterious desire and dread that push and pull me through these endless draft.

“There is no god,” says Cormac McCarthy, “and we are its prophets.”

Finally

I think this book is done. The characters move through their world with authenticity: yes! The story unfolds in an inevitably yet surprising way: yes!

I label this final iteration Agent’s Draft. Or Editor’s Draft. Or perhaps Reader’s Draft. I nudge my featherless chick from the nest.

I cross my fingers that a note won’t come back like the one Samuel Johnson sent to a hapless writer: “Your manuscript is both good and original; but the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good.”

I cross my fingers that a note won’t come back like the one Samuel Johnson sent to a hapless writer: “Your manuscript is both good and original; but the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good.”

Like James Herriot, I have become a “connoisseur of that nasty thud a manuscript makes when it comes through the letter box”—no less nasty when the thud I hear is digital.

I lash about, looking for something to blame. I’m too young. Too old. The wrong gender. The wrong colour. I live in the wrong place. My writing is too sophisticated. Too experimental. Too. Too. Too.

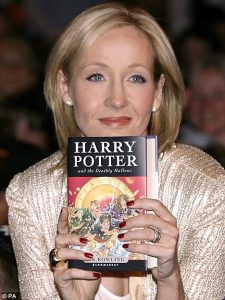

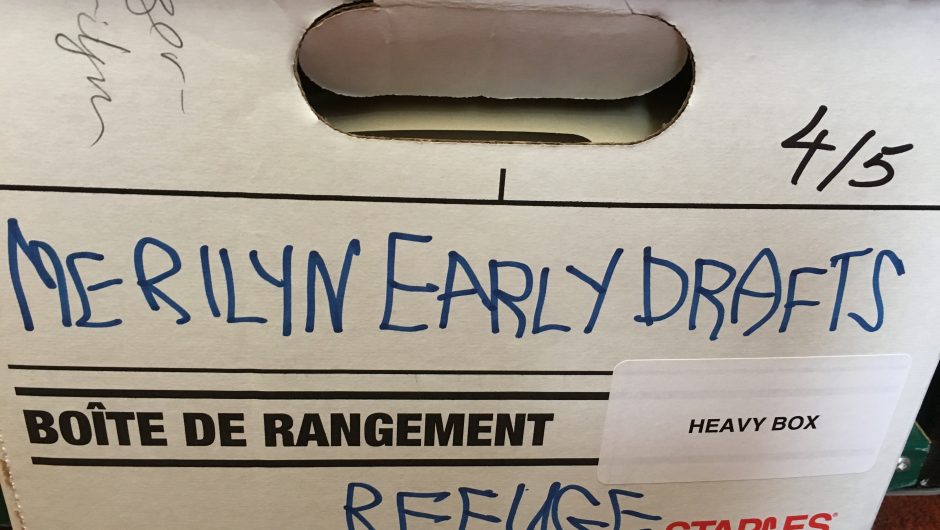

Hopeless outrage crashes over me in waves that diminish slowly, birthing contractions in reverse. In the spaces between, I try to convince myself that the rejected draft is just fine. After all, wasn’t J. K. Rowling’s first Harry Potter manuscript rejected 12 times? Wasn’t Stephen King’s Carrie was rejected 30 times. Wasn’t Gone With The Wind sent back a whopping 38 times? Even my own Convict Lover was rejected by dozens of publishers before it found a home; Refuge, too.

Hopeless outrage crashes over me in waves that diminish slowly, birthing contractions in reverse. In the spaces between, I try to convince myself that the rejected draft is just fine. After all, wasn’t J. K. Rowling’s first Harry Potter manuscript rejected 12 times? Wasn’t Stephen King’s Carrie was rejected 30 times. Wasn’t Gone With The Wind sent back a whopping 38 times? Even my own Convict Lover was rejected by dozens of publishers before it found a home; Refuge, too.

Should I courageously defend this “final draft”? Or am I foolishly clinging to a flawed version of what this book could be?

The work is too hard. Too uncertain. “I want to quit,” I say to my husband. “Quit then,” he says, knowing I won’t, but knowing too that I need to know that I can. We do this for each other.

In days, or weeks, or months, the despair softens until I think I hear the manuscript calling. Maybe a different point of view? A shift to the present tense? A new path through the story? Eventually, I listen. One possibility seems intriguing. I open the file, press duplicate, and give the file a new start-date, a new draft number.

And this, I believe, is what makes a writer. Not overweaning talent or luck or connections, but this stubborn willingness to start another draft—however that word is defined—and another and yet another until the work is well and truly done.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

My record is 20 drafts (not counting this post). What’s yours?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Comments

This reads like the initial chapter in your new dystopian novel, but I have an uncomfortable suspicion that it’s an essay.

I’ve found this post to be reassuring. My husband has suggested that the re-writing process is a form of perseveration. I prefer to think of the similarities to cabinet-making—smoothing, polishing, scuffing. I have only ever admitted to thirteen drafts, but that was a lie. I have never counted the .1’s, .2’s,.3’s etc. In each “version.”

Working on a computer makes it so easy to change a word or add or delete a paragraph without having to retype the whole manuscript that I lose count of how many versions each page undergoes before I print the whole thing out and call it a draft. And then there are the title changes: my “Up From Freedom” folder has twenty files in it, only five of which are called Up From Freedom. Maybe we can collectively come up with a definition of” draft”: two or more substantive changes equals a new draft? Oh, but then what counts as a substantive change?

Wayne just reminded me of Patricia Hempl’s description of the drafting. The first draft, she says, is written by a puppy. The second, by a cat.