Rachel Cusk’s protagonist, Faye, narrator of the novels Outline, Transit, and Kudos, is a strangely silent, receptive character who acts as a blank page on which others unspool their stories. At times heart-wrenching, philosophical, and bleakly mundane, these stories slide off her seemingly without effect—or affect. Everyone else goes on about themselves at length, but Faye reveals almost nothing of herself. She is cold and withheld—for me, a distinctly unlikeable character.

“I’m not interested in character,” Cusk says, ” because I don’t think character exists anymore.”

Have we moved past modernism and post-modernism into a post-character literary age?

In a November New Yorker interview, Rachel Cusk muses that not just literature, but life itself has become post-character: “There’s a homogeneity afoot, an oceanic pool of experience that erodes the notion of individual character and its importance.”

She goes on: “I think this is a moment in culture, generally, where people are looking again at everything that was accepted… and suddenly thinking, I’m really sick of this, and I don’t want to read it anymore.”

This brings to mind Nietzsche’s lamentation that “language is not the adequate expression of all realities.” Yet writers continue to labour in the verbal trenches, inventing characters who are easy to love and characters who aren’t.

We may be post-character, but someone still has to tell the story.

Literature is well-stocked with unlovable characters: villains like Shakespeare’s Iago, vicious mothers like Cathy Ames of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, dreadful fathers like Heathcliffe. We shrink from these literary undesirables as we shrink from unlovable people. Why? Because we’re afraid of what they’re up to? Because we don’t want to imagine that even a sliver of them exists in us?

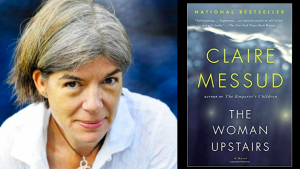

The unloveable may be despised by other characters in a story, readers may turn away from them, but we writers must embrace them. Not in the way that the Publishers Weekly interviewer meant when she asked novelist Claire Messud if she would be friends with Nora Eldridge, the angry protagonist of The Woman Upstairs.

“For heaven’s sake,” Messud exploded. “What kind of question is that? Would you want to be friends with Humbert Humbert? Would you want to be friends with … Hamlet? Krapp? Oedipus? … Antigone? Raskolnikov? Any of the characters in The Corrections? Any of the characters in anything Pynchon has ever written? Or Martin Amis? Or Orhan Pamuk? Or Alice Munro, for that matter? If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t ‘Is this a potential friend for me?’ but ‘Is this character alive?’”

“For heaven’s sake,” Messud exploded. “What kind of question is that? Would you want to be friends with Humbert Humbert? Would you want to be friends with … Hamlet? Krapp? Oedipus? … Antigone? Raskolnikov? Any of the characters in The Corrections? Any of the characters in anything Pynchon has ever written? Or Martin Amis? Or Orhan Pamuk? Or Alice Munro, for that matter? If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t ‘Is this a potential friend for me?’ but ‘Is this character alive?’”

Messud’s response kicked off a lively internet conversation about likable and unlikable characters, which segued into the question of whether fictional females face as much bias as real-life women when it comes to displaying negative emotion. “…if it’s unseemly and possibly dangerous for a man to be angry, it’s totally unacceptable for a woman to be angry,” says Messud. “I wanted to write a voice that, for me, as a reader, had been missing from the chorus.”

In the debate that followed, apocryphal stories emerged of women writers being pressured to make their heroines less sharp-tongued, more sweet-tempered. This sounds a lot like the stories of Canadian writers being told to set their stories in the United States or Europe because nobody wants to read about our few acres of ice and snow.

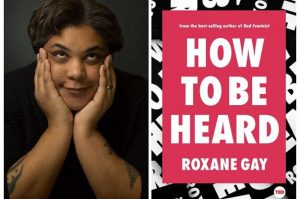

Roxane Gay sums up the character-gender debate in her BuzzFeed essay “Not Here To Make Friends.” Gay argues that ‘unlikable’ female characters fulfill a vital role in upsetting the patriarchy. Gay also acknowledges that, “in many ways, likability is a very elaborate lie, a performance, a code of conduct dictating the proper way to be. Characters who don’t follow this code become unlikable. Critics who fault a character’s unlikability … are merely expressing a wider cultural malaise with … all things that dare to breach the norm of social acceptability.”

Roxane Gay sums up the character-gender debate in her BuzzFeed essay “Not Here To Make Friends.” Gay argues that ‘unlikable’ female characters fulfill a vital role in upsetting the patriarchy. Gay also acknowledges that, “in many ways, likability is a very elaborate lie, a performance, a code of conduct dictating the proper way to be. Characters who don’t follow this code become unlikable. Critics who fault a character’s unlikability … are merely expressing a wider cultural malaise with … all things that dare to breach the norm of social acceptability.”

When editors say to me, “That character is too unlovable,” I understand that they mean the character is one-sided, lacking in complexity, without nuance. A character that is nothing but a raging lunatic is flat and uninteresting. And when a reader says they put down a book because a character isn’t lovable, it seems to me that what they are really saying is that the character isn’t engaging. Isn’t authentic. Isn’t credible.

Cassandra MacCallum, the crusty old woman at the heart of my novel Refuge, is not someone I’d want to spend a lot of time with, although in the end I was with her for 14 years, trying to figure her out, trying to figure out why I found her so compelling.

Cassandra MacCallum, the crusty old woman at the heart of my novel Refuge, is not someone I’d want to spend a lot of time with, although in the end I was with her for 14 years, trying to figure her out, trying to figure out why I found her so compelling.

I may become a lonely holdout in the post-character age, but as long as I can bend my fingers over a keyboard, as long as I can read words on page or screen, it will be human characters I crave. Not because I am looking for myself in them, and not because I’m looking for new friends.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry said that “love does not consist of gazing at each other, but in looking outward together in the same direction.” My goal as a writer is not to set a character on the page for a reader to look upon with adoration or alarm, but rather, to move a character into a reader’s life, so that they look out on the world together.

5 Comments

Love this — thanks, Merilyn.

This is such a fascinating topic for conversation and it’s funny too because Cusk’s books are ones that I’ve tried and failed to read all the way through a couple of times and it definitely had something to do with character or perhaps the lack thereof.

Just today reading in Lamott’s Bird by Bird that character drives plot.

I too love to write and read about dark and “difficult” characters — people I might well find hard to live with but want to understand and enjoy exploring on the page and in my head/heart.

So interesting! I love how you wove these books together, you data for the discussion of likeable vs real, which ever fascinates me. Thanks for this post.