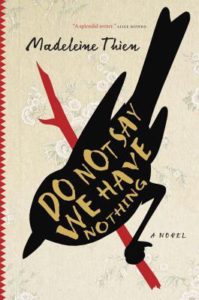

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Madeleine Thien’s Giller- and GG-winning novel, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, is set partly in China in the culturally turbulent years after the Second World War. Two sisters, Swirl and Big Mother Knife, are story-tellers who travel the country performing story cycles. “Stories, even in times like these, were a refuge, a passport, everywhere.”

Swirl marries Wen the Dreamer, “a walking cartload of books” who hand-copies pages banned by the Cultural Revolution. Later, after Swirl and Wen move to a remote village and denunciations have begun, Big Mother Knife visits to find them banished from their home, others crawling around the courtyard, lifting the paving stones, looking for the treasure Swirl buried.

But it wasn’t silver she hid, it was books.

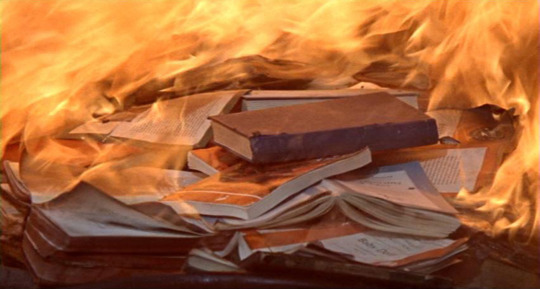

Up in Flames

Wen the Dreamer copies books to save them. In The Book Thief, after the hidden Jew teaches her to read, Liesel steals books the Nazi party is looking to destroy.

In Ray Bradbury’s classic, Fahrenheit 451, books are outlawed and burned (the the title refers to the temperature at which paper combusts). A few are ultimately saved by exiled book-lovers who memorise the texts.

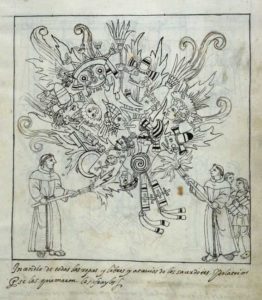

Only four—four!—of the thousands of books that existed in Mexico in 1519 survived the bonfires of the Spanish. Bishop Diego de Landa recorded the carnage:

We found a large number of books … and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all.

In the early 1990s, Merrily Weisbord and I co-wrote a book called The Valour and the Horror that prompted some Second World War veterans to launch a 500-million-dollar lawsuit against the writers, publishers, and filmmakers of the companion television series—the biggest class-action lawsuit in Canadian history. The Canadian Senate called a hearing, and within the solemn stone walls of Canada’s parliament buildings, a senator rose to recommend that the book be recalled and destroyed. Burned.

Into the Trash

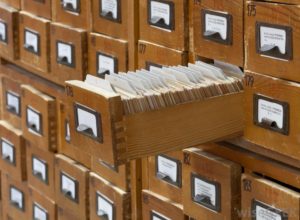

At about the same time, my local library, like every library in the country, was giving up their card catalogues in favour of searchable digital databases. I used to spend hours at those narrow wooden drawers, idly thumbing the cards, waiting for the inspiration of coincidence: looking up monarch and finding Malcolm Lowry loitering nearby, which led to Lunar Caustic and the lovely pale green luna moth.

I loved the jittery type across the top of each card, the o and e filled in by the ink-caked keys of some ancient typewriter, and below the essential details of title and author, notations in black ink or blue ink or pencil, handwritten by one librarian after another. On the backs of the cards, spelling corrections and comments, mini reviews and recommendations, directions to other books by the same author, catalogued under a secret nom de plume.

Those cards were coded conspiracies among book lovers, like the pin-pricked pages of prison library books, a silent telegraph from one reader to the next.

When my local library trashed its physical catalogue, stacks of cards were set on the checkout counter, free to readers in search of bookmarks. I took as many as I dared, worried that some catastrophe would shut down the electricity and with it, the new digital database. I didn’t worry about an obliterating fate like the fire that consumed the library at Alexandria (not then, I didn’t) but a lesser catastrophe: books still on the shelves but no way to find them.

Poof!

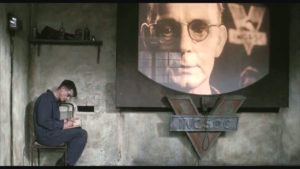

On Friday June 12, 2009, anyone who had purchased an ebook of George Orwell’s 1984 from Amazon woke up to find it gone from their Kindle. This was not a prank, although it was highly ironic, given that in the Orwell novel, Big Brother gets rid of politically embarrassing stories by sending them down an incineration chute called “the memory hole.”

In real life, it was Amazon that remotely deleted both 1984 and Animal Farm from the Kindles of paying customers. It was a legal issue, they explained—they’d bought the ebooks from a company that didn’t hold the rights—and they refunded the cost of the books. But nothing could take back the sudden, absolute realization that ebooks are not ours to keep, not even when we pay for them. What we buy is not a book, but a license to read “digital content.”

Our cash transactions in a bricks-and-mortar bookstore are anonymous. They can’t be traced. If a bookseller discovered the book he was selling was illegal merchandise, he would not be able to find you. And even if he could, he certainly could not break into your house and take the book off your shelf. But because digital retailers are selling a license, they can revoke it at any time, and because the transaction is tracked, they know exactly where to find you and your books.

Demagogues of the future won’t have to light bonfires to get rid of books. They’ll just have to type in a code.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

If there were just one book you could save, what would it be?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Comments

A lovely elegy/warning, Merilyn — thank you.

Thank you Alissa. Although there is no imminent threat, the western world is walking down a dangerous path, littered with ashes.

I remember the cards in the card catalogue too, and I miss them. Wonderful piece, Merilyn. We are digitizing everything. Cars that will drive us to our destination, in effect, digitizing the scenery so we won’t have to look at it. We can sit behind the wheel and do something else instead. My book to save? The Rebel. Albert Camus. Because I read it now and then, all over again, and expect to do so again.

Oh, what a good choice! So many books to reread!

Oh, for card catalogues and musty stacks! A wonderful essay, Merilyn.

My book to save? My choice would be A Walk With Love and Death by Hans Koningsberger (now Hans Koning), an elegant, spare and tragic historical novel I first read at 17, and have reread several times since. Extremely hard to find (in the days before Abe.com), I had a library copy photocopied and bound so that I would have it with me always. I wrote the author to let him know of my devotion — and influence on my writing — only to find that he had recently died.

As someone who now spends hours in digital libraries seeking out the voices of women, I am concerned that the works of women are often not chosen to be digitized and will thus be forgotten.

I have never read this, but will try to find it. And how true: digitization seems to favour the established choices of history.

Lovely essay, Merilyn. And how true that while researching one thing, we find so much more. Pretty well impossible to do digitally. My book to save: Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Oh, divine!