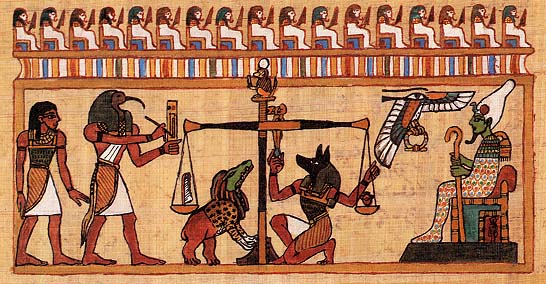

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]”The Weighing of the Heart,” one of 192 spells, incantations, and rituals that make up The Book of the Dead, describes how the heart of a deceased will be set into a tray on one side of a large scale. In the other tray, a feather from Ma’at, goddess of truth. If the heart balances the feather of truth, the dead may continue their journey into the afterlife. If the heart outweighs the feather, Ammat the devourer—a crocodile-headed creature with a cat’s body and hippopotamus hindquarters—will snatch the human heart from the scale and gobble it down.

The Book of Emerging Forth into the Light

The earliest surviving Book of the Dead—a series of hieroglyphs that label a king’s tomb—dates to 3150 BCE. Over the next 1500 years, pyramid texts, then coffin texts, were carved and painted onto walls and tombs. In 1550 BCE, the first papyrus Books of the Dead were produced, new iterations in various versions appearing until the second century CE.

Flash forward to 1798 when Napoleon invaded Egypt and a roll of papyrus painted with inscrutable hieroglyphs was handed to Vivant Denon, first Director of the Louvre museum in Paris. The grave-robbers who’d found the papyrus scrolls called them the “book of the dead men” or the “book of the dead” because they clearly belonged to the mummies they’d been buried beside. The title did not refer to the content because no one could read them at the time.

It took 25 years to break the code, and soon after, Karl Richard Lepsius published a translation, calling it das Todtembuck, or The Book of the Dead even though the running head in the margin referred to the text as “Emerging Forth into the Light.”

One Deben of Silver

The Book of the Dead is a book only in the sense that a collection of matchsticks is a book of matches. It is a gathering of texts—hymns, prayers, spells, incantations, rituals, magic formulas—written by a series of priests over 1,000 years for the purpose of assisting the dead in their journey through the underworld and into the afterlife. Some 200 versions exist from various periods in ancient Egyptian history, but no single copy contains all 192 texts.

The Book of the Dead is a book only in the sense that a collection of matchsticks is a book of matches. It is a gathering of texts—hymns, prayers, spells, incantations, rituals, magic formulas—written by a series of priests over 1,000 years for the purpose of assisting the dead in their journey through the underworld and into the afterlife. Some 200 versions exist from various periods in ancient Egyptian history, but no single copy contains all 192 texts.

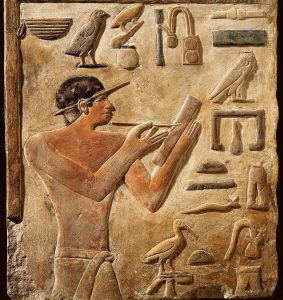

The illustrated papyri were produced by scribes, commissioned in preparation for death, mostly by men. (A rough estimate has 10 books prepared for men, for every book commissioned by a woman.) The scrolls varied in length from 40 meters to 1 meter, but they were expensive: one deben of silver apiece—half of what a laborer would earn in a year.

All in the Family

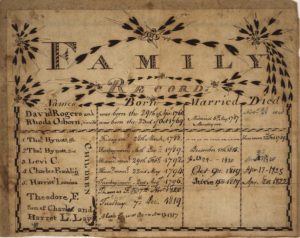

The modern version of a book of the dead, perhaps, is the Family Bible—a book handed down through the generations that records, not only visions of the Christian afterlife, but all the births, marriages, and deaths of a particular family. Other archival bits and pieces—photographs, letters, and sometimes newspaper cuttings—are often tucked inside.

The modern version of a book of the dead, perhaps, is the Family Bible—a book handed down through the generations that records, not only visions of the Christian afterlife, but all the births, marriages, and deaths of a particular family. Other archival bits and pieces—photographs, letters, and sometimes newspaper cuttings—are often tucked inside.

40 years ago, deep in a “mystery box” won at auction in Oxfordshire, England, Annamaria Bamji found such a Family Bible, with entries dating to 1774. She brought it with her to Canada, first to Kingston, Ontario, then to Victoria, BC. With the arrival of the Internet she tried tracking down the names, without luck. Then she asked a historian friend, still living in Oxfordshire, if any of them were familiar. “Oh my goodness, I just met one of them!” he exclaimed.

140 years after the first death was recorded, the Bible found its way back to its family, to a generation that never knew it existed.

El Dia de los Muertos

In Mexico, on November 2, life itself is the Book of the Dead. Ofrendas are prepared in every household, with photographs of the dear and departed surrounded by marigolds, white candles, glowing copal resin, and sugar reproductions of the favorite foods and drink of the dead.

In Mexico, on November 2, life itself is the Book of the Dead. Ofrendas are prepared in every household, with photographs of the dear and departed surrounded by marigolds, white candles, glowing copal resin, and sugar reproductions of the favorite foods and drink of the dead.

On that day, cemeteries are alive with family picnics laid out on the graves of forebears. Graveyards, year-round, everywhere, are a kind of three-dimensional book of the dead, an ambient literature of the departed, a book open to every passerby.

Digital Eternity

In my basement, I have several books of the recently dead: registries of those who signed their condolences at the wakes and funerals of deceased family members. At the time, it feels like posterity, but I’ve seen condolence books like these in junk shops and thrift stores—too important to throw in the trash; too burdened with unknown names to keep.

In the digital age, funeral homes offer online registries that allow distant friends and relatives to send condolences and tributes through the Internet. Instead of being consigned to one person’s shelf, these digital “books” remain visible for years for anyone to read and remember.

Eventually—maybe not until the lights go out forever, but even so, eventually—these digital books of the dead will vanish into the ether, as did most of their Egyptian counterparts. Museums still hold scraps and shreds of scrolls that give a glimpse of the afterlife as it was conceived five thousand years ago. What record will survive, five thousand years from now, of our beliefs regarding what happens when the body dies? Digital will be dust by then, too.

Eventually—maybe not until the lights go out forever, but even so, eventually—these digital books of the dead will vanish into the ether, as did most of their Egyptian counterparts. Museums still hold scraps and shreds of scrolls that give a glimpse of the afterlife as it was conceived five thousand years ago. What record will survive, five thousand years from now, of our beliefs regarding what happens when the body dies? Digital will be dust by then, too.

Maybe books aren’t the answer. Maybe cultural traditions will outlast every human attempt to freeze belief into words on a page.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

2 Comments

Who could ever have had a heart that weighed less that a feather? Was the weighing of the heart ceremony a way of keeping everyone out of the Afterlife?

ah, the dead, the dead, they are always with us… in a service at FIRST UNITARIAN in Toronto to celebrate the DAY OF THe DEAD, people in the congregation spoke out the name of some person they loved who had died, and there was a collective response after each name, the congretation saying together “PRESENTE” (the Spanish inflection here)… It was extraordinarily moving and although I did not speak, inwardly I recited the names of my beloved Deads and said after each, “Presente”….The power of one word, light as a feather and heavy as a stone.