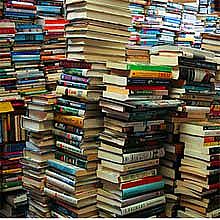

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] The tower of books on a bookseller’s front table swells the newly published author’s heart with joy. She swoons, imagining all the happy readers laying down their hard-earned dollars to take this book home, where they will slowly turn the pages, revelling in her story, finally shelving her book with all their other treasured tomes. This is the fantasy.

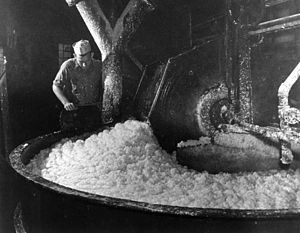

The reality is that every year around the world millions of unsold books are pulped, pitched in the nearest landfill or dissolved into a milky liquid and reconstituted as recycled paper to print yet more books.

The reality is that every year around the world millions of unsold books are pulped, pitched in the nearest landfill or dissolved into a milky liquid and reconstituted as recycled paper to print yet more books.

It is almost impossible to find out how many books are pulped each year in Canada. But in 2009 in the United States, an estimated 30-40% of books produced were returned unsold to the publisher and 65-95% of those returns were pulped—returned to the slurry from whence they came.

In 2007, BookNet Canada announced they would survey the level of book returns, but I could find no public mention of the results. An investigation by Bruce Batchelor, who interviewed Canadian distributors and booksellers to try to get at the numbers, reported that “for some genres—such as mass market fiction—returns can run up to 85%…for other genres 40% was fairly typical.”

How Books are Sold

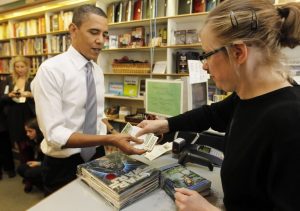

This massive waste is a consequence of how books are sold, a process unlike the sale of any other object we purchase. Basically, books are shipped to booksellers on consignment. If the books don’t sell, the bookseller gets to ship them back.

This massive waste is a consequence of how books are sold, a process unlike the sale of any other object we purchase. Basically, books are shipped to booksellers on consignment. If the books don’t sell, the bookseller gets to ship them back.

If the bookseller has overestimated sales or if the publisher overestimates the public appetite for a book, bingo—thousands of books end up at the warehouse, unwanted and unread. While small independent booksellers tend to be conservative in their orders, big-box stores tend to be more profligate: as book sales shifted from small to large outlets, the problem of returns intensified.

From Gimmick to Gargantuan Waste

This way of selling books—more akin to used clothing than art—apparently started in the 1930s when a desperate New York publisher thought up the sales gimmick to get booksellers to take his books. “Guarantee your sales—Return unsold books for exchange or refund.”

The gimmick was picked up and has become so standard that no one remembers a time when books were sold like everything else, for a firm wholesale price.

Every so often—in 1995 and again in 2006—the alarm is raised about the extraordinary waste in this system, not only in the pulping of books, but also in the unnecessary cutting of trees. In the US alone for instance, some 30 million trees are cut down annually to make books.

Pulp to Paper to Pulp

Recycling in the book business been going on for so long that it almost qualifies as a tradition. In the early 17th century, paper was so expensive that publishers often ripped pages from unwanted books to use as endleaves to bind new books.

Then, in the late 19th century, a young Nova Scotia logger and poet named Charles Fenerty proposed a solution: Why not make paper out of wood? Rags had to be manufactured, but the landscape bristled with trees that grew like grass. Fenerty died before his brain-wave became a reality, but others took up the challenge and soon the world’s books were made from trees.

Then, in the late 19th century, a young Nova Scotia logger and poet named Charles Fenerty proposed a solution: Why not make paper out of wood? Rags had to be manufactured, but the landscape bristled with trees that grew like grass. Fenerty died before his brain-wave became a reality, but others took up the challenge and soon the world’s books were made from trees.

At first, the process was a one-way street. Pulp became paper. That changed during the First World War, when the U.S. government, hard up for raw materials, inaugurated the Waste Reclamation Service. Other countries followed suit.

The percentage of recycled fibre in paper books increased by fits and starts until 2006 when Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth claimed to be the first book ever to offset 100% of the carbon dioxide generated in publishing it. That year saw a big push in “greening” the book industry. American publishers were encouraged to sign the Book Industry Treatise on Responsible Paper Use; Random House committed to raising the proportion of recycled paper in its books from 3% in 2006 to at least 30% by 2010, a target later moved to 2013.

In Canada, the environmental education of publishers was led by Canopy, best known for its successful campaign to “green” the Harry Potter series. In 2001, when Canopy informed Alice Munro that her stories in Dear Life were being printed on virgin forest fibre, she insisted her publisher stop the presses. Dear Life became the first major title by a prominent literary figure to be printed on 100% recycled paper. Munro’s support for using recycled paper back in 2001, together with other prominent authors such as Margaret Atwood and Yann Martel, helped the practice become the norm for book publishing in North America.

In Canada, the environmental education of publishers was led by Canopy, best known for its successful campaign to “green” the Harry Potter series. In 2001, when Canopy informed Alice Munro that her stories in Dear Life were being printed on virgin forest fibre, she insisted her publisher stop the presses. Dear Life became the first major title by a prominent literary figure to be printed on 100% recycled paper. Munro’s support for using recycled paper back in 2001, together with other prominent authors such as Margaret Atwood and Yann Martel, helped the practice become the norm for book publishing in North America.

Today, many Canadian publishers advertise their green-ness. A writer can find out which publishers use paper 100% certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), which books contain 10–30% Post Consumer Waste (PCW).

Pulp Friction

Pulp Friction

Green is good, but it doesn’t really solve the problem of the weird way books are sold and the consequent overprinting that sends so many books back to the recycling slurry. Wouldn’t it be better not to overprint in the first place?

Digital printing technology has taken some out of guessing out of the game of predicting bestsellers. If a book catches on or wins a big prize, a reprint can happen with a quick press of a button.

And publishers are experimenting with novel ways of getting rid of overstock. In 2012 Penguin Canada ran a Groupon offer for Steif Larsson’s Millenium Trilogy that gave consumers a terrific deal and emptied the warehouse of hardcovers after the paperback was released.

Guaranteed Destruction

Book publishers are understandably reluctant to admit how often their optimism for a manuscript fails to materialize in sales. Bookstores are equally reluctant to lose the returns policy that keeps them in a marginally profitable business. And the pulpers may not even know how many books are in the heap of unwanted paper they send to landfills and the pulping tanks.

Book publishers are understandably reluctant to admit how often their optimism for a manuscript fails to materialize in sales. Bookstores are equally reluctant to lose the returns policy that keeps them in a marginally profitable business. And the pulpers may not even know how many books are in the heap of unwanted paper they send to landfills and the pulping tanks.

But we can extrapolate the numbers: twenty years ago, the president of Guaranteed Destruction estimated that 250,000 tons of books were destroyed in the US every year. The number of books printed has steadily increased so it is safe to assume that the returns—and the pulping—have too.

Reporting in the Wall Street Journal in 2005, Jeffrey Trachtenberg called returns “the dark side of the book world,” and quoted Barnes & Noble CEO Steve Riggio as saying, “Any rational business person looking at this practice would think the industry has gone mad.”

Emerging from the Dark Side

Returns, wastage, recycling, the weird way books are sold—this subject may have moved off the front pages, but there’s no indication much has changed.

Returns, wastage, recycling, the weird way books are sold—this subject may have moved off the front pages, but there’s no indication much has changed.

Thinking about those tower of freshly minted books now makes me queasy. I glance at my ereader with new appreciation. Yes, the plastic will have to be recycled eventually, but maybe I’m saving a few trees?

Frankly, I don’t know where the solution lies. Ebooks? Print on Demand? A complete change in the way books are sold?

I look at the Gutenburg Fingerprints stacked on the bookseller’s table and throw a little wish their way: may you end up loved on a bookshelf somewhere, not burning in a fiery dumpster or drowning in a chemical bath, my words melting from the paper pages.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

8 Comments

Merilyn,

Is it true that books signed by the author cannot be returned to the publisher?

Best,

Roberta

I think that used to be true, but as far as I know, it isn’t true any longer. I’ve seen my signed books in stores where I have never signed them!

This is very timely for me, as I have a new book (launching in Kingston 23, 24 October by coincidence) and am halfway through your wonderful Gutenberg’s Fingerprint — at the spot where you discuss digital printing. Borealis and I decided to print Lizard Love in a small edition, one I thought I could mostly sell over the next year, with them keeping enough for orders/promo/awards, and quick digital reprinting anytime. They also mount each book as an e-book. I (mostly), and they (as backup), essentially become the booksellers. Although a few will end up in bookstores, I haven’t taken them to any bookstore, not even my favourite one, which launched the book but tellingly didn’t ask for any copies — although we sold several dozen. They probably figured that was the audience, gone. When they opened, I offered and they took a full range of my work — part of which was on the shelf for a month or so but has now completely disappeared. An earlier deposit of wordmusic material never appeared at all. This is, unfortunately, typical it seems. And entirely discouraging. I’ve likewise had little luck with on-line direct sales, though I haven’t pursued this properly. Being, like your hub, basically a Luddite. Face-to-face, hand-to-hand seems the new and only, very limited, mode. Back to Gutenberg, and before. I love books. In a world of instant communication and entertainment, we’re talking about hand-crafting, here. What shall I do with my extensive poetry library? Mush it down and make paper? Harrumph!

Do NOT make paper with your poetry library!

It’ a dilemma, isn’t it? Hard not to get discouraged.

This was an excellent blog post.