[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Colmán of Elo was tired. Tired of reading and tired of the fly that buzzed across his vellum page.

“Sit!” he commanded the fly. The fly turned its mosaic eyes upon the blessed saint who wrote Airgitir Crábaid, now the earliest example of Old Irish Prose.

“Sit there!” commanded Colmán, pointing to the last word he’d read. And so the fly sat, patiently waiting until the saint returned to his reading in the Abbey of Muckamore.

Where we left off

This origin story of the bookmark is undoubtedly apocryphal, but when, exactly, did bookmarks become our companion to books?

The word itself is a youngster, coined in 1840. For a decade or two before that, the device was known as a bookmarker or pagemarker or sometimes just a marker. But what about readers five hundred, a thousand, two thousand years ago? Did they devour books in one sitting, for fear of losing their place?

Of Butterflies and Dogs’ Ears

Without a bookmark, a reader has few choices. Butterfly the book, leaving it smashed on its face like a drunk in the sun. Pinch a page corner and snap it over in a dog’s ear. Stab a pencil point in the margin. All too aggressive, surely, for the gentle pastime of reading. Such injury is grievous and permanent, that broken spine, that scar at the corner a lasting reproach.

Without a bookmark, a reader has few choices. Butterfly the book, leaving it smashed on its face like a drunk in the sun. Pinch a page corner and snap it over in a dog’s ear. Stab a pencil point in the margin. All too aggressive, surely, for the gentle pastime of reading. Such injury is grievous and permanent, that broken spine, that scar at the corner a lasting reproach.

Headbands and Fore-edgers

Almost as soon as the book was invented in the first century, readers looked for a way to remind themselves where they stopped reading. Books then were rare and hand copied: the place-marker must not mar the page.

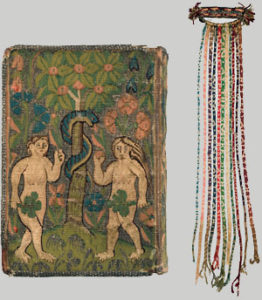

The oldest surviving bookmarker is from the 6th century, a strip of ornamented leather attached by a strap to the cover of the book. It was discovered under the ruins of the monastery of Apa Jeremiah, near Sakkara Egypt.

The oldest surviving bookmarker is from the 6th century, a strip of ornamented leather attached by a strap to the cover of the book. It was discovered under the ruins of the monastery of Apa Jeremiah, near Sakkara Egypt.

This is the ancestor of those lovely ribbons that dangle from the spines of high-quality hardcover books, draping up or down between the pages. If only every book was so beribboned!

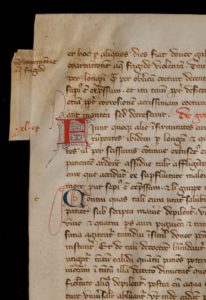

Between the 13th and 15th centuries, a different approach prevailed: a thin strip of parchment glued to the fore-edge of the page or threaded through a tiny slit n the margin parallel to where the reader stopped.

Between the 13th and 15th centuries, a different approach prevailed: a thin strip of parchment glued to the fore-edge of the page or threaded through a tiny slit n the margin parallel to where the reader stopped.

Fore-edge markers look a bit like an index tab. Sometimes the tab was made by tearing a piece off the page itself, sometimes a permanent tab was glued to the parchment, and sometimes, a reader would laboriously trim the margin to create a tiny tab marker.

The Memory Wheel

At some point, though, the bookmark was divorced from the book and became a freestanding companion that could be used in book after book: cords and ribbons and embroidered, tatted bits that hung down between pages, anchored by a gob of metal or bead that rested on the top edge of the book. Occasionally, triangles that slid over the page corner.

At some point, though, the bookmark was divorced from the book and became a freestanding companion that could be used in book after book: cords and ribbons and embroidered, tatted bits that hung down between pages, anchored by a gob of metal or bead that rested on the top edge of the book. Occasionally, triangles that slid over the page corner.

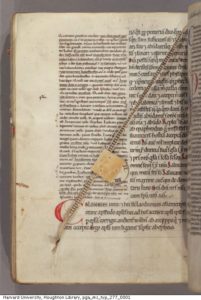

The most ingenious was a little rotating disc made of parchment or light metal that was attached to the book by a string so that it could slide top to bottom. The disc was inscribed with Roman numerals I to IV. When a reader wanted to mark their place, they slid the disk down to the proper level and turned it to indicate the column where they stopped reading: first and second columns on the left, third and fourth on the right.

Don’t lick your fingers!

Reading exploded with the Industrial Revolution, and so did bookmarks. The first detached bookmarks appeared in 1850s: richly embroidered silk, four-color printings, filigreed silver inset with jewels.

Reading exploded with the Industrial Revolution, and so did bookmarks. The first detached bookmarks appeared in 1850s: richly embroidered silk, four-color printings, filigreed silver inset with jewels.

Back then book buyers had to slit open their own pages, and it didn’t take long for entrepreneurs to market a combination bookmark-pagecutter so readers could slice as they read.

Bookmarks were issued as mementoes, and soon as advertising. An Austrian manufacturer of cigarette papers produced 1,000 bookmarks in the 1930s, featuring writers from around the world. A 1920s Dutch soap manufactory printed the back with 16 rules for the proper treatment of books:

6. Don’t make dog-ears at pages

11. Don’t eat while reading

16. Don’t insert other objects as bookmarks than real bookmarks into your books.

These Dutch bookmarks obviously didn’t make their way to Japan, where you can buy realistic fake-food bookmarks, saving your place with a rasher of bacon, a fried egg, a pancake or a slice of salmon.

These Dutch bookmarks obviously didn’t make their way to Japan, where you can buy realistic fake-food bookmarks, saving your place with a rasher of bacon, a fried egg, a pancake or a slice of salmon.

Bookmarks are for Quitters

Even in the digital world, bookmarks denote a page, but not one made of paper. On my Kindle, a lovely image of a ribbon slides down to mark a page I want to go back to. On my computer, I save “bookmarks” of web pages I hope to revisit (and rarely do).

Oddly, digital bookmarks were conceived before www was born. In 1989, digital inventor Craig Cockburn drafted a proposal for a touch-screen device called “PageLink” that would function as both an ereader and a browser—with bookmarks. It was never developed but three years later the first bookmarks appeared as part of the first browser, Mosaic.

Oddly, digital bookmarks were conceived before www was born. In 1989, digital inventor Craig Cockburn drafted a proposal for a touch-screen device called “PageLink” that would function as both an ereader and a browser—with bookmarks. It was never developed but three years later the first bookmarks appeared as part of the first browser, Mosaic.

Bookmarks are a universal feature of browsers now, but readers must miss their dog-ears. In 2011, Kindle revealed plans for a DE (dog-eared) version with creased corners, giving the reader the impression that their ebook is well-thumbed.

Project Bookmark

At the other end of the scale is Project Bookmark, the very solid bronze brainchild of Miranda Hill of Hamilton, Ontario. These lovely plaques mark imagined stories that take place in real landscapes, bookmarks that literally blaze a literary trail across Canada.

At the other end of the scale is Project Bookmark, the very solid bronze brainchild of Miranda Hill of Hamilton, Ontario. These lovely plaques mark imagined stories that take place in real landscapes, bookmarks that literally blaze a literary trail across Canada.

Top Marks

My husband collects bookmarks, the paper kind. Although he finds them at festivals, libraries, street fairs, and just about anywhere anybody has anything to sell, he only collects bookmarks from bookstores. He has almost a hundred fanned in a holder on his desk, reminders of books he’s bought and stores he’s browsed. Recently, I brought him a perfect gift from Charlottetown, PEI: a bookmark from a bookshop named Bookmark.

My husband collects bookmarks, the paper kind. Although he finds them at festivals, libraries, street fairs, and just about anywhere anybody has anything to sell, he only collects bookmarks from bookstores. He has almost a hundred fanned in a holder on his desk, reminders of books he’s bought and stores he’s browsed. Recently, I brought him a perfect gift from Charlottetown, PEI: a bookmark from a bookshop named Bookmark.

A friend of mine, a great reader and one-time editor, also collected bookmarks, but only those printed one side. As she read, she’d note on the blank side every grammatical error, misspelling, and infelicitous phrase before sending the bookmark off to the offending publisher.

Making My Mark

I am not a collector at heart. I’m just as likely to use whatever comes to hand when I need to save my reading place: a safety pin, a tatted doily, a stick of chewing gum, a rubber band.

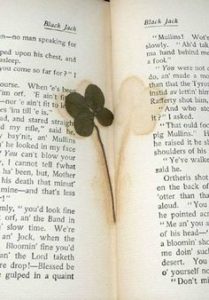

Like Colomán, I’m partial to living bookmarks. Every so often I come across a four-leaf clover, a pressed violet or daisy in a book that I read as a girl and it comes back to me, that feeling of lying in the grass, reading for hours, my fingers riffling through the greenery, transported to another world.

Like Colomán, I’m partial to living bookmarks. Every so often I come across a four-leaf clover, a pressed violet or daisy in a book that I read as a girl and it comes back to me, that feeling of lying in the grass, reading for hours, my fingers riffling through the greenery, transported to another world.

Erik Kwakkel, leader of the Turning Over a New Leaf project that explored the relationship between medieval book technology and cultural change describes what he came across in Zutphen’s chained library when he was thumbing through one of the first printed books from the 1460s.

“I had this astonishing encounter: a leaf put there by an ancient reader. It was hardened and felt like leather. A person 400 years or more ago picked up this leaf from the street on his way to the library. Was it fall? Was he looking forward to a long read in the dark library?”

Bookmarks can do that: mark not only the reader’s place but the reader, too, capturing a hint of character, a preference for broken spines or lucky leaves.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

How do you mark your place in books?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Comments

My daughter made a beautiful bookmark for me and it was my Christmas gift from her this year. In six months, I have not yet lost it, which is unprecedented. It is a very precious thing, although I find that streetcar transfers are also very useful bookmarks and I appreciate that they;re marked with the date which is always remarkable when I come upon them while rereading. Anyway I love this post!

Thank you, Kerry. Wayne and I haunt used bookstores and I am always so happy (and intrigued) when I come upon the oddities people use as bookmarks. We once bought a Bliss Carman first edition and his bookmark was a letter from one of his many lady-loves—also dated!

Lovely post! When Richard and I travel, I bring back bookmarks. When I begin a book, I go through my drawer of bookmarks to pick out the one that matches the spirit of the book.

Over the years I’ve tried to come up with a system to keep track of the books that each bookmark has been used for. I’ve tried a bookmark blog, taking photos, a scrapbook, a file-system, but the best I’ve managed so far is a simply post-it note I stick to a bookmark listing the books it has graced. Sometimes, although rather rarely, I even manage to note down where and when I bought the bookmark.

I’m a bookmark collector at heart, but a poorly organized one. For me, the most important moment — and it’s one I take seriously — is matching a bookmark to a book.

I found the bookmark blog I started:

http://thebookmarkblog.blogspot.ca

I should keep it up!

That is so interesting! I am woefully willy-nilly by comparison. This morning I came across the prompts for this bookmark blog, which I fully intended to mention. Hugh Barclay, the hero of Gutenberg’s Fingerprint, has just hand-printed a series of “Clandestine Bookmarks” that he is leaving here and there and everywhere. They contain provocative questions and quotes: Have you thanked the person who taught you to read? So what are you doing to make the world a better place? And one from Picasso: Computers are useless. They can only give you answers! I hope he adds another Pablo favourite: Art requires disrespect.

All of your posts are so informative and interesting! I love them.

I use anything I can find on my messy desk as a bookmark – art postcards from the AGO, paint swatches in shades of blue, occasionally a pencil. I also love using sticky notes, especially the ones I have that are shaped like whales. My sister recently gave me a bookmark she bought in Toronto that is shaped like a leaf and doubles as a pencil (regrettably, I am one of those people who writes in my books, so this bookmark is perfect for me).

Paint chips! What a great idea. When A New Leaf came out, I found some lovely bookmarks that were the exact colour, size, and shape of a blade of grass. I put one in every copy I signed. That made me very happy. But a bookmark as pen? Not for me! I’ve never been able to bring myself to write in a paper book—which is one of the appeals of my ereader, where I can notate with abandon and never mar the text.

“Don’t lick your fingers!” would have been good advice for the victim in a mystery novel, the title of which I won’t give here because I don’t want to spoil the book for future readers. But the killer murdered his victim by impregnating the corners of the book he was reading with arsenic: when the reader licked his fingers and turned a page, a small amount of poison was transferred to his tongue. I don’t remember how far he got, but he didn’t finish the book. And he didn’t leave a bookmark.