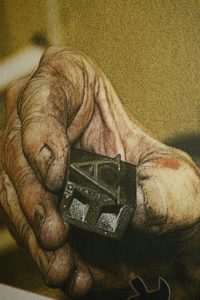

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]“If I don’t have it, I make it,” Hugh Barclay says, sawing a groove into the body of a letter A so he can insert a short sliver of lead to create an accented vowel. “What else is a person to do?”

Hugh is over 80. When he was born in the 1930s, he would have been called a craftsman. In the 1940s and 50s, a how-to kind of guy. In the 1960s and 70s, a do-it-yourselfer. Now he is a classic Maker.

Hugh is over 80. When he was born in the 1930s, he would have been called a craftsman. In the 1940s and 50s, a how-to kind of guy. In the 1960s and 70s, a do-it-yourselfer. Now he is a classic Maker.

At 10, Hugh built himself a workshop in his parents’ basement. At twelve, he designed and built his own sailboat. By seventeen, he was tearing apart cars and putting them back together. At twenty-three, he invented a lightweight leg brace for a friend, which propelled him into orthotics, where he invented half a dozen orthotic devices including the dynamic-tilt wheelchair. When ink seeped into his blood, he bought an antique letterpress, pulled it apart and put it back together again, learning to operate it the same way he learned how to build it: by doing.

The first book to roll off Thee Hellbox Press was A Letter to Teresa, a thank-you to the Walpole Island First Nation for including his adopted Cree daughters in their powwow. He published dozens more, and in 2012, invited me to work with him to produce The Paradise Project, a process I track in Gutenberg’s Fingerprint: Paper, Pixels, and the Lasting Impression of Books.

Winter of Artifice

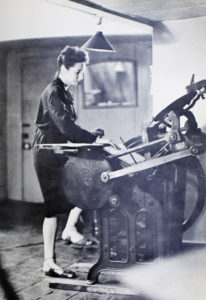

With The Paradise Project, I became one of a long line of writers who have fallen in love with giving their words physical form. One of the most articulate is Anaïs Nin, who set up her own small press in 1942 in New York City. She taught herself typesetting and did almost all the manual work of self-publishing a letterpress edition of her third book, Winter of Artifice.

In The Diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume 3, 1939-1944, she writes about the particular joys of making:

“You live with your hands, in acts of physical deftness . . .You pit your faculties against concrete problems. The victories are concrete, definable, touchable. You can touch the page you wrote. . .. At the end of the day you can see your work, weigh it. It is done. It exists.”

I laugh, reading about how she uses soap boxes as shelves to hold her tools and inks, how she arrives at her printing loft, “loaded with old rags for the press, old towels for the hands.” Hugh’s print shop is a chaos of ‘making,’ too: an old cookie tin for a “hellbox” where he tosses damaged type; bits of projects from the past three decades scattered across every surface and taped to the walls.

Maker Millennials

In high school, I took home economics and learned how to make blanc mange and an A-line skirt. My mother showed me how to make a cherry pie and embroider a Christmas stocking. My dad taught me how to change a tire. My great aunt instructed me in the art of hoeing a straight furrow, planting seeds.

In high school, I took home economics and learned how to make blanc mange and an A-line skirt. My mother showed me how to make a cherry pie and embroider a Christmas stocking. My dad taught me how to change a tire. My great aunt instructed me in the art of hoeing a straight furrow, planting seeds.

Most of today’s Millennials had two working parents. By the time they got to high school, home economics and shop had been retired along with art and music. No one showed them how to sew a seam or cut up a chicken or change the oil in their car. No wonder they are flocking to DIY—oops, Maker—sites to teach them what they yearn to know.

A whiff of the counter-culture utopianism that drove 1960s DIY is driving Maker Culture today. Making is the flip side of consuming. It is active, not passive; doing instead of acquiring; local instead of global; not disposable, but sustainable.

The opposite of corporatism and siloed individualism, making implies learning through informal, collective networks where people share and pool knowledge. The motivation is not just the object that is produced; makers are looking for self-fulfilment and dare I say it, fun.

“Press on!” Hugh exclaims as I struggle to find the right letters and get them upside down and backwards into the chase. He punches his fist in the air. “Joy is the objective!”

A Horse Designed by a Committee

At the same time I was hand-typesetting The Paradise Project, I was working on a digital edition with my book-designer son. Hugh was busy adapting his wood-and-metal type when he needed a diphthong or some tight kerning. Meanwhile, my son pointed me to Titillium.

At the same time I was hand-typesetting The Paradise Project, I was working on a digital edition with my book-designer son. Hugh was busy adapting his wood-and-metal type when he needed a diphthong or some tight kerning. Meanwhile, my son pointed me to Titillium.

Titillium is a typeface born in 2012 at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Urbino, Italy. It began as an art-school assignment to collectively create a family of open-source fonts to be shared freely through a web platform. Each year, a fresh crop of students works on the project; graphic designers are encouraged to develop their own versions and add images of how they use the typeface to a database of case histories.

Not exactly typeface designed by committee, and not individual innovation, either.

“It’s the way of the future,” my son says.

The Gutenberg Effect

Technology—the art of making, the application of knowledge for practical purposes—connects the body to the mind.

Technology—the art of making, the application of knowledge for practical purposes—connects the body to the mind.

“The relationship to handcraft is a beautiful one,” Anaïs Nin wrote. “You are related bodily to a solid block of metal letters, to the weight of the trays, to the adroitness of spacing, to the tempo and temper of the machine. You acquire some of the weight and solidity of the metal, the strength and power of the machine. Each triumph is a conquest by the body, fingers, muscles.”

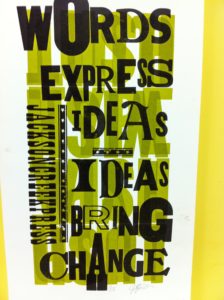

Gutenberg is often credited with inventing the printing press, but a press consists of many moving parts. His fundamental innovation was the creation of movable type, a modular technique for bringing together the 26 letters of the alphabet into an endless variety of words and sentences and fixing them so that page after identical page could be printed, then the letters released to be reused to create new pages.

That may seem like a purely technical enterprise, but as Nin points out, the physical action of making has an added benefit: it reverberates from the hand back up into the brain, into the intellect and the imagination.

“The writing is often improved by the fact that I live so many hours with a page that I am able to scrutinize it, to question the essential words. In writing, my only discipline has been to cut out the unessential. Typesetting is like film cutting. The discipline of typesetting and printing is good for the writer.”

Make America Make Again

Three years ago, Barack Obama announced a National Week of Making (June 17-23), to encourage making, mentoring, maker organisations, and to recognise individuals who contribute significantly to Making and to the Maker Movement.

Three years ago, Barack Obama announced a National Week of Making (June 17-23), to encourage making, mentoring, maker organisations, and to recognise individuals who contribute significantly to Making and to the Maker Movement.

And it is a movement. DIY is one of the most popular categories on Pinterest. Etsy hosts more than a million makers selling their artisanal products. Craft nights are replacing book clubs. Libraries and museums are being turned into “Makerspaces.”

Brilliant new concepts rarely appear out of the blue. More often, the key elements have been bumping up against each other for a while, waiting for someone with the insight, the foresight, and the audacity to try something new. Waiting for a maker.

“More Aha! than Abacadabra!,” I say to Hugh.

“Good girl. You’ve got it!” he says.

Give makers the tools and they become creators; they can change the world.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

What did you make today?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Comments

good article

Maker Culture reminds me of the time Merilyn and I worked at Harrowsmith magazine, from the early 1980s until 1990. Harrowsmith was truly a counterpoint to consumerism: readers were given the information and sources they needed in order to make things, or fix things, or grow things, for themselves. For me, at the time, the goal was always self-sufficiency. The sense of independence, not only in work-related things but also in thinking for oneself, is, perhaps ironically, the essence of civilized society. Harrowsmith provided the necessary tools for everything from sharpening a hoe to figuring out who to vote for. It’s great to see that that has grown into a culture. Harrowsmith itself sprang from the back-to-the-land movement of the 1970s. The Maker Culture is a welcome continuation of it. The magazine has died, but the seeds we planted then live on.

How true! And lovely to realize its roots wind back to the late 19th century Arts & Craft movement, which was a reaction to the impoverished state of decorative arts as a result of the industrial revolution. Every revolution has its counter-revolution—thank goodness! The social activism associated with the Arts & Craft Movement—and also today’s Maker Movement—is explored in an excellent New Yorker article http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/01/13/making-it-2

I learned to knit wih my grand mother, to cook with my mother and with friends . I taught my daughters to sew and cook . I learned printmaking with different artists and did teach it many years.

Using our hands is a pleaasure and a great way to stay in contact with the universe and the history of mankind.

Your article is inspiring .Merci!