[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This week, a female mallard with a slight limp came waddling through our condo courtyard, sizing up the planters beside each front door, hopping into one, wiggling her breast into the debris of last year’s plantings, then jumping out to try the next. Two years ago, this same female sat for ten weeks on soil barely covered by the dried tops of my potted daffodils and tulips. Roofers working nearby left corn and cut-off Coke bottles filled with water.

My writing room looks out on the eave where an American Crow perched every morning, waiting for the mallard hen to leave her eggs for a walkabout, a snack, or a dip in the river. Alerted by the mobbing call of grackles, I’d fly shrieking down the stairs as the crow swooped towards the planter-nest, my banshee cries driving it off. Day by day, the crow grew bolder until it stood its ground beside the duck eggs so long, I had to flick its stiff black feathers to get it to move. On the day the chicks were due to hatch, I woke to a shatter of eggshells around the planter and ugly greenish smears on the ground.

Phoebe!

Phoebes—which, like chickadees, shout their own name—are among the first of the insect-eating songbirds to arrive in the spring. Shortly after Louise de Kiriline Lawrence became interested in birds in 1940, she watched two phoebes courting on the sill of her bedroom window, “a thrilling little affair full of phoebe grace and low twitterings.” A few hours later, the female was building her nest, gathering mud and wet moss to drop on a narrow ledge above a window of Louise’s chicken coop. The muddy mess slid to the ground. The phoebe made trip after trip, escorted by the male, each billful of nesting material sliding off her chosen site. After two days, Louise took pity on the birds and extended the board with a strip of wire mesh. “She fluttered to the ledge, dismayed at the sight of the wire, and dropped her mud and moss on the ground. She made several more fruitless trips, obviously expecting to see the ledge resume its familiar appearance.”

Phoebes—which, like chickadees, shout their own name—are among the first of the insect-eating songbirds to arrive in the spring. Shortly after Louise de Kiriline Lawrence became interested in birds in 1940, she watched two phoebes courting on the sill of her bedroom window, “a thrilling little affair full of phoebe grace and low twitterings.” A few hours later, the female was building her nest, gathering mud and wet moss to drop on a narrow ledge above a window of Louise’s chicken coop. The muddy mess slid to the ground. The phoebe made trip after trip, escorted by the male, each billful of nesting material sliding off her chosen site. After two days, Louise took pity on the birds and extended the board with a strip of wire mesh. “She fluttered to the ledge, dismayed at the sight of the wire, and dropped her mud and moss on the ground. She made several more fruitless trips, obviously expecting to see the ledge resume its familiar appearance.”

The next day the phoebes abandoned the coop. Louise tracked the female to the garage, where she was hard at work placing her muddy moss on a triangular shelf under the eave, sculpting the clay with “a snuggling movement, then a half-turn, then again she burrowed her breast into the nest-cup.” Five days later the nest was done, lined with fine sticks and weedy tendrils, and four days after that, the first egg was laid. Louise posted a sign at the driveway: Please pass around the corner of the garage quickly, quietly, and without looking!

Louise knew something was wrong when she saw the birds at her bedroom window, examining the log cabin eave with interest. Sure enough, a predator had eaten three eggs and pierced a fourth, leaving only one intact in the nest at the garage. For the third time that spring, the female chose a nesting site—this time, the ledge above Louise’s window. She tucked her bill-loads of mud into the farthest, darkest corner under the eave, lining the nest-cup with threads pulled from a piece of felt Louise tied to a pin-cherry tree.

Louise knew something was wrong when she saw the birds at her bedroom window, examining the log cabin eave with interest. Sure enough, a predator had eaten three eggs and pierced a fourth, leaving only one intact in the nest at the garage. For the third time that spring, the female chose a nesting site—this time, the ledge above Louise’s window. She tucked her bill-loads of mud into the farthest, darkest corner under the eave, lining the nest-cup with threads pulled from a piece of felt Louise tied to a pin-cherry tree.

The female was on the nest almost constantly, while the male perched before her on the tip of Louise’s open bedroom window. Even after the young hatched and the adult birds set to foraging, they rarely let the chicks out of their sight, and neither did Louise. “The day the red squirrel ran up on the peak of the roof and peered over the edge of the eave, and the day the garter snake chased the leopard frog into the grass under the nest, were days of painful dread for me. I wanted to surround the little nest with a protective screen against the dangers of the world, but I could not. I believe that for all wild things, the natural interplay between failure and success, safety and danger, must not be eliminated lest life for them lose its edge, and living its zest.”

Sixteen days after the chicks hatched, the birds stood up and stretched their legs. The next day, the young phoebes—the parents’ third try at raising a family—fluttered one by one from the nesting shelf into a tangle of honeysuckle as Louise watched through her window.

High-Rise

I spent last September in Louise’s log cabin, which is almost unchanged from when I last visited her there 35 years ago. The forest around the cabin has climaxed, the woods crisscrossed now with deadfall, but as soon as I arrived I heard the woodpeckers and chickadees she loved.

I spent last September in Louise’s log cabin, which is almost unchanged from when I last visited her there 35 years ago. The forest around the cabin has climaxed, the woods crisscrossed now with deadfall, but as soon as I arrived I heard the woodpeckers and chickadees she loved.

I was too late for most of the warblers and the Eastern Phoebe, too, I thought. But then a phoebe landed on a low branch, flicking its tail and pausing, as if to make sure I got a good look. On my way back to the cabin, I prowled around the garage, the shed, the house, checking the eaves for nests. I found two—a fresh one on an old piece of lattice leaning against the wall of the house, and another, an elaborate three-tiered affair, on a ledge just outside Louise’s bedroom window, evidence that phoebes continue to raise their families there, after eighty years.

Woman as Anomaly

I thought about Louise’s phoebes as I cast about for a form in which to write the story of her remarkable life. She first asked me to be her biographer in 1989, after I wrote a profile of her for Harrowsmith Magazine. I said, Sure!, as I often do to new projects, having no clear idea what biography was, let alone how to go about writing one.

At its simplest, a biography is an account of someone’s life written by someone else. But that definition can arc from a scholarly arrangement of facts to a fictionalized recreation. In the late 1980s, biography was a fairly strict academic form, which didn’t appeal to me. Since then, however, the genre has loosened its stays. Over the years, now and then, I’d pick up a biography and think, No, not like that, or, Hmm, maybe that, until a writer friend lent me The Fall of Frost by Brian Hall, a literary biography of the poet Robert Frost that takes about as many liberties as a writer can. Hall describes his role as “rushing in where historians refrain from treading.” His approach has created a sub-genre: la vie romancée, a biography written like fiction that maps not a definitive life, but how an individual life might have evolved.

At its simplest, a biography is an account of someone’s life written by someone else. But that definition can arc from a scholarly arrangement of facts to a fictionalized recreation. In the late 1980s, biography was a fairly strict academic form, which didn’t appeal to me. Since then, however, the genre has loosened its stays. Over the years, now and then, I’d pick up a biography and think, No, not like that, or, Hmm, maybe that, until a writer friend lent me The Fall of Frost by Brian Hall, a literary biography of the poet Robert Frost that takes about as many liberties as a writer can. Hall describes his role as “rushing in where historians refrain from treading.” His approach has created a sub-genre: la vie romancée, a biography written like fiction that maps not a definitive life, but how an individual life might have evolved.

My commitment to Louise weighed heavily. I agreed with Thomas Carlyle that “No great man lives in vain; the history of the world is but the biography of great men,” except for his failure to mention the female half of human population. What particularities were involved in writing a biography of a woman? I put off writing Louise’s story and instead read the lives of women, including The Red shoes: Margaret Atwood Starting Out by Rosemary Sullivan, which isn’t a biography so much as a portrait.

My commitment to Louise weighed heavily. I agreed with Thomas Carlyle that “No great man lives in vain; the history of the world is but the biography of great men,” except for his failure to mention the female half of human population. What particularities were involved in writing a biography of a woman? I put off writing Louise’s story and instead read the lives of women, including The Red shoes: Margaret Atwood Starting Out by Rosemary Sullivan, which isn’t a biography so much as a portrait.

“We still think of a powerful man as a born leader,” said Margaret Atwood, “and a powerful woman as an anomaly.”

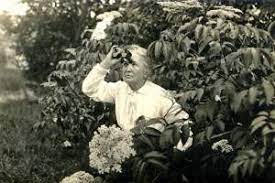

Louise was no anomaly—she was part of a lineage of women tramping the woods to discover the true nature of nature. Women like Althea Sherman who, when she discovered a nest of sickly baby phoebes in her barn, washed the walls around the nest with sublimate of mercury and sopped the nest with the solution, too. She removed the hair lining from the nest, washed it and dried it with a flatiron, then returned it to the nest and set in the nestlings, having first picked lice from their newborn bodies—118 lice from one hatchling half the size of her thumb. How could I tell Louise’s story without telling the story of Althea Sherman, too?

Bird Lesson #2

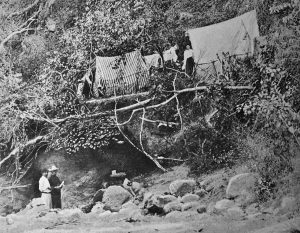

In the winter of 2018, I read Two Bird Lovers in Mexico, published in 1905, the first book by the acclaimed naturalist William Beebe. As the title implies, there were two people on that trip—Beebe and his wife, Mary Blair Rice. She appears in photographs but is rarely mentioned, although she was crouching in ditches and wading through swamps to observe the birds, too. She was allowed to write the final chapter, “How We Did It,” which is all about what to wear and how to pitch camp and gather supplies in pre-tourist northern Mexico, but even so, her voice is distinct:

In the winter of 2018, I read Two Bird Lovers in Mexico, published in 1905, the first book by the acclaimed naturalist William Beebe. As the title implies, there were two people on that trip—Beebe and his wife, Mary Blair Rice. She appears in photographs but is rarely mentioned, although she was crouching in ditches and wading through swamps to observe the birds, too. She was allowed to write the final chapter, “How We Did It,” which is all about what to wear and how to pitch camp and gather supplies in pre-tourist northern Mexico, but even so, her voice is distinct:

“To the woman who is courageous enough to defy the expostulations of her friends and to undertake a camping trip to Mexico, let me say that I congratulate her on having before her one of the most unique and fascinating experiences of her life; that is if she goes in the proper spirit. And the proper spirit is to be interested in everything and to have one’s mind firmly made up to ignore small discomforts.”

After she divorced Beebe, this intrepid woman published 11 travel books and 7 novels under the name Blair Niles. When she discovered The Explorers Club refused to admit women, she formed The Society for Woman Geographers, which still exists.

Curiously, it was Blair Niles, Althea Sherman, Margaret Atwood, and Rosemary Sullivan who blazed a path for me to Louise. Like that little phoebe, I never stopped feeling the urge to write Louise’s biography, but my first attempts were stillborn. Eventually, these women led me to a form broad enough and sufficiently accommodating to write Woman, Watching.

Curiously, it was Blair Niles, Althea Sherman, Margaret Atwood, and Rosemary Sullivan who blazed a path for me to Louise. Like that little phoebe, I never stopped feeling the urge to write Louise’s biography, but my first attempts were stillborn. Eventually, these women led me to a form broad enough and sufficiently accommodating to write Woman, Watching.

If a bird were named for its behaviour—and not for its call or for a Roman goddess or for its so-called discoverer, their friends, and benefactors—then this busy flycatcher, with its pluck and persistence and stubborn loyalty to an idea might be named not Phoebe, but Tenacity.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Comments

Love this. Tenacity. A fine reminder of what it takes. Thank you.

Hi Merilyn:

Thank-you for your unique and telling expressions such as “sizing up the planters,” “the genre has loosened its stays,” and “stubborn loyalty to an idea.” Such care with words is one of the reasons that I so much enjoy reading your work.

I so agree, Jean Gower. A writer to savour.

Thank you Jean and Sandra. I often think of you both as I write, our long friendship with words.

LOVE THIS. Working on publishing the Whispers now (Nimbus has it on an exclusive for now). Will send you a copy if you would like and can see yourself in the acknowledgements. Hope you are having a happy easter. Would NEVER have finished my book with your mentoring from beginning to end.

Cheers,

Carmeiita

Congratulations, Carmelita!

Lovely to read this, as I sit in my office and watch the chickadees, finches and various sparrows hopping and flying around the deck. I was hoping to see a little nest, but now that I’ve read this about crows, I definitely do not want to see one. We have befriended two crows who visit every day, and I’d prefer not to see their murderous intentions.

Thanks for posting this, Merilyn, and I look forward to the book.

Ah yes, Nature—red of tooth and claw!