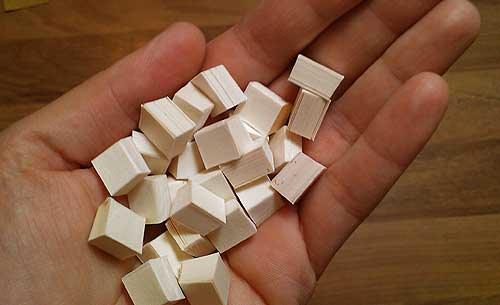

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] In one creation tale, from Tumblr’s zwischendenstuehlen, books are hatched as tiny tomes — blind and naked creatures. Diligently, the writer makes little jackets to keep them warm during the first dark season of their lives. Those that make it through their various trials grow up to be big and strong and wise, taking their place on the shelf beside their older sisters and brothers.

But seriously, where do books come from? For Ian Rankin, there’s usually a question he wants to answer, a theme he wants to explore. Hilary Mantel admits that the idea that kicks off a book is often quite slight and circumstantial: “I see something, hear something, think ‘That would make a story,’ and then I find its vast hinterland.”

In her book, Process: The Writing Lives of Great Authors, Sarah Stodola looks at how well-known contemporary writers got the brainwave that became their first book.

1. Loved Ones

David Foster Wallace found his spark in a comment from a college girlfriend who said she’d rather be a character in a book than a real person. Wallace couldn’t stop thinking about what she said, what she meant by it, what the difference was, really, between a fictional character and a real-life person. The idea grew into The Broom of the System, a novel about a woman who doesn’t believe in her own reality.

David Foster Wallace found his spark in a comment from a college girlfriend who said she’d rather be a character in a book than a real person. Wallace couldn’t stop thinking about what she said, what she meant by it, what the difference was, really, between a fictional character and a real-life person. The idea grew into The Broom of the System, a novel about a woman who doesn’t believe in her own reality.

2. Newspapers

Joan Didion, while working at Vogue in New York, happened upon a newspaper item about a man charged with killing his farm’s foreman in the Carolinas. The image stuck. She transported the scene to her home state of California and it became the core of her first novel, Run, River.

3. Illness

An Anatomy of Inspiration, written by Rosamund Harding and published in 1942, includes the experience of T.S. Eliot, famous for his stream-of-consciousness poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Eliot notes that physical illness can act as a gateway to creativity. He argues that serious illness provides not only the light-headed obliteration of the detritus of daily living, but allows for what he calls “an incubation period,” a time free of life’s insistent burdens during which ideas can be processed by the unconscious.

An Anatomy of Inspiration, written by Rosamund Harding and published in 1942, includes the experience of T.S. Eliot, famous for his stream-of-consciousness poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Eliot notes that physical illness can act as a gateway to creativity. He argues that serious illness provides not only the light-headed obliteration of the detritus of daily living, but allows for what he calls “an incubation period,” a time free of life’s insistent burdens during which ideas can be processed by the unconscious.

“This disturbance of our quotidian character… results in an incantation, an outburst of words which we hardly recognise as our own (because of the effortlessness),” he writes, adding the caveat, “though we do not know until the shell breaks what kind of egg we have been sitting on.”

Illness isn’t the only way to lift the weight of reality. Dreams and sleep can do it, says Saul Bellow: “You never have to change anything you got up in the middle of the night to write.” Or writing itself: “You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you,” advises Ray Bradbury in Zen in the Art of Writing: Releasing the Creative Genius Within You.

4. Good Health

On the other hand, Lewis Carroll, in his essay Feeding the Mind, proposes that for the imagination to work properly, it must be nourished regularly and well. Just as the body thrives on a healthful diet, he advises that “it is one’s duty, no less than one’s interest, to ‘read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest’ the good books that fall in your way.”

For Penelope Lively, the idea for a new book “comes to me, in a strange way, from reading rather than from living or observation.” Or, in the words of Stephen King, “If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that.”

How to Birth a Book

Writers are generally prodigious readers, but according to James Webb Young, reading is not enough. In his little 1939 book, A Technique for Producing Ideas, available now on Kindle, Young eschews mysticism and serendipity. Instead, he lays out five steps in the creative process. Knowledge comes first and is basic to good creative thinking, he says, but it has to be digested for those nuggets of received wisdom to emerge as something new.

Einstein called this process intuition. Young likens it to what takes place in a kaleidoscope. “Every turn … shifts these bits of glass into a new relationship and reveals a new pattern…the greater the number of pieces of glass the greater the possibilities for new and striking combinations.”

Einstein called this process intuition. Young likens it to what takes place in a kaleidoscope. “Every turn … shifts these bits of glass into a new relationship and reveals a new pattern…the greater the number of pieces of glass the greater the possibilities for new and striking combinations.”

Young emphasizes training the mind not only to gather new information but to be alert to these new relationships. Then comes a stage he calls Unconscious Processing.

“Drop the problem completely and turn to whatever stimulates your imagination and emotions. Listen to music, go to the theater or movies, read poetry or a detective story.”

Some writers take naps. I take a long, hot bath. My bet is that Rebecca Solnit goes for a walk. Thinking, she points out in Wanderlust: A History of Walking, is generally thought of as ‘doing nothing’ — and doing nothing in our production-obsessed culture is increasingly frowned-upon. Walking is a way of doing nothing and something at the same time, allowing the mind to wander “so readily into religion, philosophy, landscape, urban policy, anatomy, allegory, and heartbreak.”

Some writers take naps. I take a long, hot bath. My bet is that Rebecca Solnit goes for a walk. Thinking, she points out in Wanderlust: A History of Walking, is generally thought of as ‘doing nothing’ — and doing nothing in our production-obsessed culture is increasingly frowned-upon. Walking is a way of doing nothing and something at the same time, allowing the mind to wander “so readily into religion, philosophy, landscape, urban policy, anatomy, allegory, and heartbreak.”

Solnit is not alone in extolling the virtues of not-doing. Of being present rather than productive — calming the chaos of the quotidian so the imagination can soar. Contemporary research confirms Freud’s belief that daydreaming is essential to creative thought. Wendell Berry, too, wrote that in solitude, where one is without human obligation, “one’s inner voices become audible. One feels the attraction of one’s most intimate sources”.

If we’re lucky, says Young, our period of Unconscious Processing propels us to the fourth stage, the Ah-ha! Moment. Exhilarating and exuberant, inspiration dawns, seemingly out of nowhere. Then the fifth stage sets in, what Young calls “the cold, gray dawn of the morning after.” This is where Ah-ha! Is put to the test of Oh yeah? Where inspiration must learn to walk and talk and fly or be left by the roadside with all the other brilliant but unworkable ideas.

The Road to Refuge

Three things came together to spark Refuge, my novel that will come out later this year.

I was reading Hayden Herrera’s biography of Frida Kahlo, and a line jumped out at me. “She had many nurse-companions.” I hit my forehead with the flat of my hand. Of course she did! Anyone that sick would have had a practical nurse at her side throughout those first years after the trolley she was riding in was T-boned by a bus.

My great-aunt Mabel was not only a practical nurse, she was also a collector. After she died, her scrapbooks found their way to me. I was flipping through her record of medical oddities, wondering about Frida Kahlo’s practical nurses, when I came upon a tiny clipping: “Dr. Maurice Brodie has just received shipment of 4,000 rhesus monkeys at the New York City harbour.” What on earth would a person want with 4,000 monkeys?

My brain seething with monkeys and Mexican art, I opened the door to my rural neighbour, a fellow so full of stories they bubble out every time he sits down. He told me about a very old woman he’d just visited. She lived alone on an island and had rigged up her cabin so she never needed anything from anybody. What brought her there, I wondered. What would happen if someone invaded her sanctuary, someone who needed something from her?

Nursing, monkeys, solitude. Mexico, New York, the wilds of eastern Ontario. As John Steinbeck wrote, “Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen.”

Inspired, I read and read and wrote, and finally, after a dozen years, I turned the kaleidoscope just so and Ah-ha! the pieces miraculously fit together. A book was born.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

Where do you get your most startling, most profound, most enduring creative ideas?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Comments

Great post, Merilyn.

For me, it’s Mortality.

I’m a childless only child perched at the end of the last branch of a withering family tree.

I’d like to leave something behind… for posterity, perhaps. And If I don’t tell the story, who will?

If I tell it well enough, it may just outlive me.

Have you ever listened to the Hamilton original cast album? (or do only gay guys do that?)

At the finale, Alexander Hamilton and his son have both died. Alexander’s widow Eliza is left to pick up the pieces.

After hearing it for the first time, I cried for about an hour, and I realized why I’m telling my story.

Listen to it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NrMkdZtqiVI

Thank you Chris. I hadn’t listened to that score — it is so moving. Mortality is a powerful spark. More like a full-on pyrotechnica!

Thank you for this Merilyn. A great way to start my day. I think I’m with Bradbury on this one. Also, Eliot. But for me the need to negotiate meaninglessness, the way a word will spark a riff, my need to make order out of chaos, yes, need to distill chaos of mind. Sometimes truly, writing is a dropping to knees in wonder and becomes form of prayer.Praise. Exclamation of joy. Call and response ? For that, stillness is required. But for a book: a line, a story, a sign ( I mean that literally. ) a situation, a big clang and me dreaming what if. .. what if…also, where books come from for me is never the same–each book so different. A wonderful question and even if we think we know the spark — a great MYSTERY. Again, thank you.

Yes, mystery. It seems this is something that can only be parsed in retrospect. Nothing can actually *provoke* the magic— although, for me as for Eliot (I was so happy to find his words!), bedridden illness always has this miraculous effect on me.