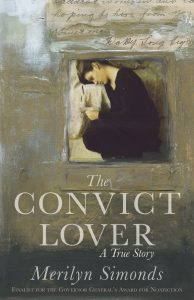

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] After seven years of researching and writing, I finally printed out a draft of my nonfiction novel The Convict Lover. The stack of pages was higher than a child’s booster seat. Even in my innocence, I knew prospective publishers were unlikely to read a 750-page prison tome, so I hauled out my scissors and glue pot—this was 1994, the digital dark ages—and attacked my hard-won words. Six months later, the manuscript was lean and muscular, reduced to a mere 88,000 words from its original 200,000. My heart, along with countless, priceless scenes, lay in shards on the floor.

We still call it “cut” and “paste,” even though editing is now accomplished with the click of a couple of keyboard keys, thanks to Larry Tesler, an engineer at Xerox in the 70s. Hours spent putting in a comma and taking it out—Oscar Wilde’s explication of his writing day—requires no retyping, no White-out, no red lines scored through the text, no special editing scissors with blades long enough to cut across an 8½”-wide page.

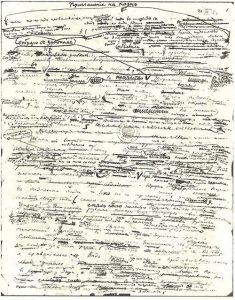

In a quaint quote, Vladimir Nabokov admitted that “I have rewritten—often several times—every word I have ever published. My pencils outlast their erasers.” Gone are the pencils, and the erasers, too.

Genius Editors

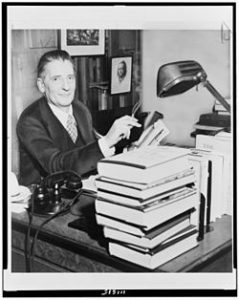

I cut my writer’s teeth on the Max Perkins mythology, immortalized in the movie Genius, that behind every successful writer stands a savvy, eagle-eyed editor. I dreamed of being taken on by such an editor, who would slash and burn my wagon-load of pages into a brilliant novel, as Perkins did with Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel, ejecting 90,000 superfluous words from the story.

I soon learned that, historically, editors have been a mixed blessing. Thomas Wentworth Higginson was a friend and literary advisor to Emily Dickinson, but after her death, when he edited her poems for publication, he removed much of the radically original punctuation we love.

More recently, Gordon Lish gutted Raymond Carver’s stories, often reducing the text by more than half and making his own additions. Carver described Lish’s edits as “surgical amputation and transplant that might make them someway fit into the carton so the lid will close.”

Never a fan of Carver’s minimalism, I finally fell in love with his prose when The New Yorker published his original version of the story that became “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.”

Even knowing the backroom shenanigans some editors got up to, it was a shock to discover that Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Charles Dickens’ editor, declared the original ending of Great Expectations too sad. Pip and Estella should end up together, he said, and that’s the story generations of readers have read.

Editable

I had the good fortune of being edited by Ellen Seligman, editor to Margaret Atwood, Elizabeth Hay, Michael Ondaatje, Jane Urquhart, David Adams Richards, Anne Michaels, and dozens more. Before she took me on, she invited me to lunch. Midway through our meal she leaned across the table. “Are you editable?” she said. I had no idea what she meant. Yes! I said.

I had the good fortune of being edited by Ellen Seligman, editor to Margaret Atwood, Elizabeth Hay, Michael Ondaatje, Jane Urquhart, David Adams Richards, Anne Michaels, and dozens more. Before she took me on, she invited me to lunch. Midway through our meal she leaned across the table. “Are you editable?” she said. I had no idea what she meant. Yes! I said.

And so, when she suggested that in my novel The Holding, the two protagonists must meet at the end and have it out, I argued weakly, “But that’s not in their characters,” then went back to my desk and wrote the confrontation scene.

“That doesn’t work,” Ellen said.

“How about this?” I emailed back, attaching the ending from the novel’s first draft.

“Perfect!” she said.

Michael Pietsch, who was David Foster Wallace’s editor, captures the interplay that made working with Ellen so invigorating. “Editing with a writer is a joyous collaboration—not even a collaboration, but a conversation, a colloquy, a back-and-forth.”

The best editors, I’ve come to realize, are not Lish-like Svengalis, but smart, articulate ur-readers who, if the chemistry is right, will engage a writer in the deepest conversations of her literary life.

Kill Your Darlings

Long before a manuscript is assigned to an editor, however, a writer must grow her own second set of eyes.

Long before a manuscript is assigned to an editor, however, a writer must grow her own second set of eyes.

It’s not easy to follow the classic advice to kill your darlings, but writers learn to be ruthless. And when they do, the satisfactions are sweet.

During his time in Germany, Nathan Englander wrote 200 pages of a new novel. Other projects took over, but eventually, he pulled out those 200 pages and spent a few weeks working on them. “I threw them all out today,” he said finally. “And I’m feeling light as a feather.”

A typical editing day is a high drama of tragedy and triumph, with a voiceover dubbed by your best editor. Here is what a random day from last August looks like, during the final edit of Refuge, to be published this fall:

1. Changed the name of one of the main characters from Juan Carlos to Carlos.

2. Finally cut the St. Lawrence Seaway scene, which my editor has been insisting for months must go.

3. Inserted a key phrase into the first page, otherwise unchanged since I wrote it in 2004.

4. Changed the verb tense in the last section from past to present to signal a change in the character’s mindset.

5. Changed the verb tense in the last section from present to past to make it more readable.

6. Changed the verb tense back to present, readers be damned!

7. Okay, okay, changed the verb tense back to past.

8. Added more detail about Necrophorus americanus

9. Deep-sixed several descriptions Ellen would call “overly generous.”

10. Consulted with Burmese-speaking Beta Reader.

11. Rewrote dialogue of Burmese character.

12. Note for tomorrow: develop character of Don Arturo, who seems to have crept from the margins to the centre of the story.

13. Changed verb tense back to present. Love it!

Umpteenth Revision

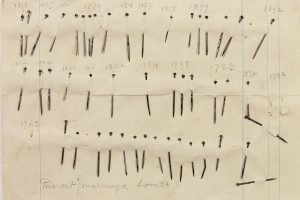

Jane Austen made her edits with straight pins, crossing out unwanted text with brown iron-gall ink and pinning into those spots small pieces of paper written closely with new sentences. This was not an original idea: archivists at the Bodleian library have traced pins as an editing tool back to 1617.

JK Rowling mapped out her Harry Potter books in detail before she started writing, revising the plan until it was too scribbled over to make sense, then she’d start fresh—again and again, through umpteen revisions.

I loved the physicality of the scissors, rubber cement, and paper-clipped insertions of my first book edits. I was less enamoured with digital cut-and-paste, fearful of what might be lost as I revised my prose over and over again. My fear dissolved when I discovered Scrivener, a word processing application that allows me to snap pictures of the text I am about to edit, preserving it in case the revision turns out to be worse than the original.

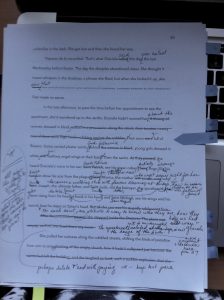

Even so, I still print every one of my fifteen or so drafts, scribble over them in black, then blue, then red ink before inputting the changes. As I ease towards the final draft, I print on pink, then green, then blue paper in an effort to trick my eyes into seeing what is actually on the page. Finally, I read the last draft out loud, sometimes recording it, hoping my ear will pick up the last errors and infelicitous phrases my eyes have missed.

Stop!

There’s a saying that a book is never finished, it’s just whisked out of a writer’s hands by an editor who yells, Stop!

There’s a saying that a book is never finished, it’s just whisked out of a writer’s hands by an editor who yells, Stop!

Last summer, while I was editing Refuge, I was also reviewing the text of a new edition of The Convict Lover, released just last week.

It was a painful read. Almost 30 years had passed since I wrote that book: I wanted to crawl back inside every sentence and make it better. I soon realized that if I let myself change even one word, I’d be revising the entire text. After all, I am not the same person I was then: I would tell the story differently now.

Thank goodness, I was saved by my inner editor.

Stop! I whispered to myself, and left well enough alone.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

Do you have a happy/sad/cutting edge editing story to share?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Comments

Encouraging. May even try pins and scissors

(I have stopped editing to chase agents and publishers. Who knows? a great editor may be hiding at the end of one of those queries,

Love your posts.

Cheers, Carmelita

Loved reading this! Johanne

I’m smiling!

Merilyn, I love this!

I also loved reading this!

Also, I cut down my new book by 40%. I’ll never worry about cutting again.

It’s amazing isn’t it? You think it can’t possibly be done, and then, slimmer, it is so much better.

After finishing a book, I find I can go back to read something that I had written before that book but which I had thought was terrible and unfixable, and so had abandoned. I usually find that it is indeed terrible but not unfixable. I can become my own Gordon Lish.

Have just published my first collection of new poetry in 9 years — can’t believe it, so long! There was no lack of poems, but I was mired in that bog of thinking the poems were good, hearing from editor friends that they were terrible, rewriting into rigorously satisfying grossly cut versions, realizing how much I’d now left out, taking them to another audience which loved them without the slightest discrimination, realizing that wouldn’t work, trying again and again and again…. Finding a couple of really high editors — poets I greatly admire, imagine could never aspire to join — who loved my work in ways I never guessed and suggested cuts I’d never imagined… In the end, my most useful editor is the publisher (in this case, Marty Gervais), who insisted over what became five years that I had to get a book to him. So, eventually, and under mind-numbing terror, I did submit and only revised at the final stage four, no five, times. The book (Haunt, Black Moss) arrived this weekend. I reread it with fear, and found only a couple of minor typos — my fault, in fact — and one line I regret cutting at that 5th edit, though in fact I probably should have cut it. Definitely one of my darlings: what a great line — “Spent and glad and amazed.” Gone gone gone, probably for the better. And maybe the beginning of a new poem. Oh, did I mention that I was an editor of art catalogues (with highly sensitive art experts writing them) for 20 years? It’s such a roller coaster, on both sides. But, as an editor, you have to pretend to be calm and certain and smiling. Now, with a book I like and am beginning to be (sometimes) proud of, I’m in the slough that follows. Does it matter anyway? Who will read the darn thing? Merilyn, I kept your blog to read until I had an almost quiet moment. It’s healing and helpful.

Happily for 90-year-old Gordon Lish, every single one of the writers he edited without exception that I can think of including Raymond Carver, eagerly embraced all of Gordon’s edits, thanked him for them, and many dedicated books to him in gratitude. Then there are the critics and the readers who bought Raymond Carver’s Lish-edited books in such huge quantities. More importantly, time will tell; so far Lish gets two thumbs up almost entirely across the board.