[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] March marks the beginning of the new year for indigenous peoples in this part of the world, and for gardeners everywhere. The sense of renewal that requires real effort to conjure on January 1 comes naturally in March. It’s spring, the equinox is past, the sun is now in ascendance and the world is bursting with blossom and courting display.

In March, especially on International Women’s Day, the focus is on women, which always makes me optimistic that the full gender spectrum will rise to equal presence throughout the year.

News from the World

An Ode to the Power of Words

On March 8, Sandra Cisneros (a Mexican-American writer living in San Miguel de Allende) accepted the PEN/Nabokov award for achievement in international literature. Poet, novelist, and memoirist, she is author of a dozen books including The House on Mango Street, Caramelo, A House of my Own, and my personal favourite, Woman Hollering Creek.

In an impassioned acceptance speech, Cisneros dedicated her award to a poetic list of word-workers as well as to those “divided by borders, the mothers and father punished for seeking asylum, the children traumatized by separation,” and “all who know writing is a spiritual act, who have faith writing can transform the lives of others, who have been resurrected by writing, who are transforming and resurrecting the world with their words.”

Read her full speech or listen to it here.

Women’s Manifesto

In 2017, the PEN International’s 83rd World Congress in Lviv, Ukraine, unanimously passed the PEN International Women’s Manifesto.

In 2017, the PEN International’s 83rd World Congress in Lviv, Ukraine, unanimously passed the PEN International Women’s Manifesto.

Presented by Jennifer Clements (left), a feminist poet and novelist who lives part-time in San Miguel too, the Women’s Manifesto strongly endorses the rights of women writers for the benefit of everyone.

Studies around the world, and most recently, the Emilia Report in Britain, have found a marked bias against women in the quantity and the type of coverage of the books they write. Women are less likely to be reviewed and less likely to be nominated for and to win prizes. The consequences can be life-threatening: when a writer is imprisoned for their work, humanitarian groups such as PEN use reviews and awards to determine their eligibility for a release campaign. Fewer women typically appeared on PEN’s roster in part because women writers were less likely to meet these criteria.

The Manifesto may help change that:

The Manifesto may help change that:

“The first and founding principle of the PEN Charter asserts that ‘literature knows no frontiers’. These frontiers were traditionally thought of as borders between countries and peoples. For many women in the world – and for almost all women until relatively recently – the first, and the last and perhaps the most powerful frontier was the door of the house she lived in: her parents’ or her husband’s home.

“For women to have free speech, the right to read, the right to write, they need to have the right to roam physically, socially and intellectually.

“PEN believes that the act of silencing a person is to deny their existence. It is a kind of death. Humanity is both wanting and bereft without the full and free expression of women’s creativity and knowledge.”

Download the Women’s Manifesto here.

Oh, Bidie-in, Where be your Chuddies?

Oh, Bidie-in, Where be your Chuddies?

134 years ago, the first installment of what became the Oxford English Dictionary was published. Its 352 pages covered only A to Ant, but even so, sold about 4,000 copies, a bestseller in its time.

Last year, in an attempt to expand its regional vocabulary. the OED launched a “Words Where You Are” appeal to mark the 90th anniversary of the first full edition. The 2019 update, launched this month, includes a sampling of accepted suggestions from around the world, local words such as chuddies (underpants in India), bidie-in (unmarried cohabiting couple in Scotland), gramadoelas (unsophisticated rural region in South Africa), and jibbons (spring onions in Wales), which should be ready for pulling any day now.

News from my Casita

On March 8, in honour of International Women’s Day, the National Arts Centre Orchestra Performed Life Reflected, an original symphony by Zosha de Castri, based on the Alice Munro story “Dear Life,” which I adapted for the project.

In May, the orchestra will take this astonishing multi-media symphony to Europe, performing on May 17 in Paris at La Seine Musicale, and on May 26 in Gothenburg at the Gothenburg Concert House.

I lived for a short time in Gothenburg, a place I wrote about in a story called “Navigating the Kattegat” in The Lion in the Room Next Door, and my new work-in-progress has its roots in Sweden: strange confluences that make it hard to resist following the NAC east across the ocean.

From the Department of How-Time-Flies

I celebrated the first day of spring by dancing in Plaza Civica, where a Mexicano band tunes up the first Sunday of each month to play cumbia, cha-cha, salsa, danzón, and more. My cumbia teacher from four years ago pulled me onto the cobbles and somehow, once I stopped thinking, my feet remembered the steps. I can’t recall my tap-dance to “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” when I was seven, but the go-go routine my friend Nancy and I danced to “Wipe-out” has never faded.

I celebrated the first day of spring by dancing in Plaza Civica, where a Mexicano band tunes up the first Sunday of each month to play cumbia, cha-cha, salsa, danzón, and more. My cumbia teacher from four years ago pulled me onto the cobbles and somehow, once I stopped thinking, my feet remembered the steps. I can’t recall my tap-dance to “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” when I was seven, but the go-go routine my friend Nancy and I danced to “Wipe-out” has never faded.

The connection between dancing and writing may seem tenuous, but not for Zadie Smith, who asks: “What can an art of words take from the art that needs none?” She answers herself: “Lessons of position, attitude, rhythm and style, some of them obvious, some indirect.” And: “Writing, like dancing, is one of the arts available to people who have nothing. The only absolutely necessary equipment in dance is your own body.” As Virginia Woolf points out, “For 10 and sixpence, one can buy paper enough to write all the plays of Shakespeare.”

Book Report

When I started this quarterly newsletter, I shared interesting literary websites through “Links I love,” but the time seems right, this being the point of balance of the solar year, to shift to thumbnail reviews of recent books that have “stayed read” — their characters, ideas, and images entering me, altering me in some significant way.

Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli

Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli

Valeria Luiselli is a provocative Mexican writer now living in the US. I was impressed with her debut novel, Faces in a Crowd, I devoured The Story of My Teeth and Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in 40 Questions, and now she has truly captivated me with Lost Children Archive, an auto-fiction story of a family’s road trip to the Mexican border—a profoundly moving, twinned illumination of children and migration.

Miriam Toews describes Women Talking as “a reaction through fiction” to true-life events at a remote Mennonite community in Colombia. The subject matter is disturbing and the structure of the novel—presented as minutes of series of women’s meetings—is also troubling, given that the minutes are taken by a man. At first, I was irritated to read women’s voices filtered in this way, but I trust Miriam Toews as a writer and so I persevered. By the end, no other format seemed possible for this terrifying, tragic, uplifting story.

Best Little Bookshop

Brittany Bond haunts used bookstores in New York City, especially the dollar shelves outside the Strand, looking for good used paperbacks by women writers. Posting her finds on Instagram garnered her a following and she began reselling the books, at first from home, and since January, from a book cart called Common Books, which can be found on the streets of the Lower East Side.

Brittany Bond haunts used bookstores in New York City, especially the dollar shelves outside the Strand, looking for good used paperbacks by women writers. Posting her finds on Instagram garnered her a following and she began reselling the books, at first from home, and since January, from a book cart called Common Books, which can be found on the streets of the Lower East Side.

“I’ve noticed that a lot of people, when they see someone reading a book by a female writer they don’t recognize, they assume it’s fluff or trash,” Bond says. She aims to change that.

The cart, which has a special seat for her two-year-old daughter Margot, holds paperbacks by literary icons such as Virginia Woolf, Alice Walker, and Lucy Maude Montgomery, but many surprises too, such as Louisa May Alcott’s romantic thrillers and her own childhood copy of Anne of Green Gables.

Imagine a book cart in every city! The idea is eminently transportable: paperbacks because they are lightweight; women writers because they are underrepresented in the public conversation; and used books because they carry a history, like a literary chain letter, from reader to reader.

https://www.instagram.com/commonbooks/

A Final Word

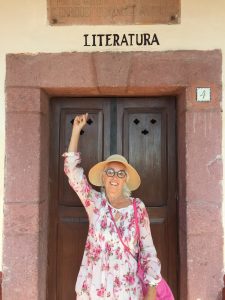

Today we leave San Miguel de Allende for our annual migration north to Canada. On our final walkabout, we visited the Casa de la Cultura, which served the city as a waterworks from 1943 until it was converted at the turn of the millennium to a municipal cultural centre, with special rooms in the “house” for music, dance, theatre, visual art, and literatura.

Today we leave San Miguel de Allende for our annual migration north to Canada. On our final walkabout, we visited the Casa de la Cultura, which served the city as a waterworks from 1943 until it was converted at the turn of the millennium to a municipal cultural centre, with special rooms in the “house” for music, dance, theatre, visual art, and literatura.

Literature is ever-present in this city, where the vegetable market is named for its 19th century literary son—writer, poet, and journalist Ignacio Ramírez—and where the Bellas Artes theatre bears his pen name, El Nigromante. The Necromancer.

From one literary city to another, we travel back to Kingston, Ontario, to a long line of writers from the author of the first Canadian novel, Julia Catherine Beckwith Hart, through Robertson Davies and Matt Cohen to Helen Humphreys and Sarah Tsiang.

I stumbled without intention on these literary places, but it is no accident that I call them home.

Happy reading,

4 Comments

A wonderful newsletter as always. Happy travels home to you and Wayne. An umbrella might be in order!

Oops! How could I confuse the equinox with the solstice??? Apologies for the first version of the intro—never pays to write when you are rushing to pack.

Thanks for another great LitBits, Merilyn. I love that photo of you dancing!

I love that dancing photo! And, as always, a wonderful LitBit. Happy landing. Miss you already. x0x