[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The pages are so swollen we have to pry the books from their shelves with a long screwdriver, levering against the after-effects of the flood. A few thin volumes at the outer edges seem almost dry. With his sleeve, Wayne wipes the mantle and lays them down flat. “I think these can be saved!” he says, his voice sharp with the kind of hope that knifes up from despair.

I haven’t written this blog for three months. This is where I start again.

Not everything was destroyed by the tap that sprung off its copper mooring, opening a fountain that dripped through the house for less than twenty-three hours, collapsing ceilings, swelling walls with paint balloons, buckling floors. It is four days since we got the call in Mexico, our first day back in our ruined house. Furniture sags under splats of drywall; the more fortunate pieces huddle in a dry corner, like sheep in a storm. On the lower shelf of the coffee table, a single plaster paw print gives evidence of where Odysseus, our cat, sheltered in the downpour. The air is thick with damp and the whirring of a dozen industrial dehumidifiers.

Not everything was destroyed by the tap that sprung off its copper mooring, opening a fountain that dripped through the house for less than twenty-three hours, collapsing ceilings, swelling walls with paint balloons, buckling floors. It is four days since we got the call in Mexico, our first day back in our ruined house. Furniture sags under splats of drywall; the more fortunate pieces huddle in a dry corner, like sheep in a storm. On the lower shelf of the coffee table, a single plaster paw print gives evidence of where Odysseus, our cat, sheltered in the downpour. The air is thick with damp and the whirring of a dozen industrial dehumidifiers.

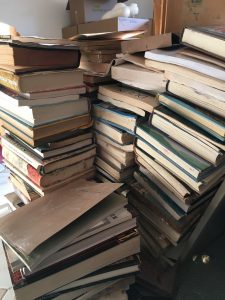

We go first to the bookshelves in our library of Canadian books. Two walls of shelves escaped the steady rain and dribbling waterfalls that coursed through the seven-level house. One wall stands at the centre of the deluge—hundreds of books collected over a lifetime, dripping now like things fished out of the toilet. “Charles Sangster,” I say, pinpointing the starting line of our loss, and then where it ends: “Jan Zwicky.” Between those two, the entire life’s work of Duncan Campbell Scott, Carol Shields, Elizabeth Spencer, Yves Theriault, Catharine Parr Traill, Bronwen Wallace, Sheila Watson, Ethel Wilson, so many more. Most of the books are first editions. Many are signed. Some are so rare, we can never replace them, not at any price.

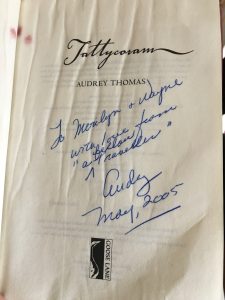

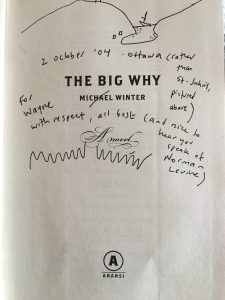

Many of the living authors are friends. Diane Schoemperlen. Audrey Thomas. Miriam Toews. Jane Urquhart. Michael Winter. Tim Wynne-Jones. Sean Virgo. The inscriptions are heartbreaking. I photograph them all. “We can contact these writers,” we console each other. “We’ll buy their books again.”

Many of the living authors are friends. Diane Schoemperlen. Audrey Thomas. Miriam Toews. Jane Urquhart. Michael Winter. Tim Wynne-Jones. Sean Virgo. The inscriptions are heartbreaking. I photograph them all. “We can contact these writers,” we console each other. “We’ll buy their books again.”

Wayne lifts each one off its shelf. They pry apart with a strange sucking sound. Delicately, he lifts the pages until he gets to the publishing data. I note the title, author, publication date, and edition on the Schedule of Loss the insurance company has given us. Don’t bother writing them all down, the agent said, just give us a total. But I do write them down. We insist on it. This isn’t a schedule of loss so much as a record of the passing of dear friends. We owe these books that much, at least.

One by one, we lay the unsalvageable in soggy piles in the middle of the library floor.

Then, amidst the wreckage, something strange happens.

“I remember buying this book,” Wayne says, “at The Word in Montreal. Morgan was a baby. The bookstore opened the day she was born.”

Holding Helen Weinzweig’s Basic Black with Pearls, I think first of the story of that housewife and her affair with the mysterious man from the Agency, their rendezvous in exotic places arranged through coded notes stuck in issues of National Geographic. He recognizes her by her dress—basic black with pearls—a costume she discards as she returns to herself. The book is thick with memories. I remember Diane Schoemperlen, early in our friendship, urging me to read it. The book was a writing workshop: the sharply pruned prose, the strange dialogue that skewed deep into the characters, the perfect pacing. Flipping through the damp pages, an old feeling comes welling back to me: there is no right age to be a writer. I was under 40 when I read this novel, already feeling too old to be working on my first literary book, but Helen Weinzweig was 58 when she made her brilliant debut, and that gave me hope.

We pull wonky, plaster-splattered chairs up to the shelf. Time slows. The stink of mould, pages that dissolve under our touch, it all disappears as we lose ourselves in the particular world of each book—not just the story, but the finding, the reading, the sharing of it. We return each morning to our seats in front of the destroyed shelves of books, eager to relive these fragments of our past that have slipped from active memory, recalled now as the foundation stones of our writing and reading lives.

We pull wonky, plaster-splattered chairs up to the shelf. Time slows. The stink of mould, pages that dissolve under our touch, it all disappears as we lose ourselves in the particular world of each book—not just the story, but the finding, the reading, the sharing of it. We return each morning to our seats in front of the destroyed shelves of books, eager to relive these fragments of our past that have slipped from active memory, recalled now as the foundation stones of our writing and reading lives.

The mould that I could hardly bear to look at in the beginning becomes beautiful. Each day the fuzz grows thicker, the crust more pungent. Blues and pinks and bright orange, a yellow the colour of daisy pollen.

With a start, I recognize this mould, although I have never seen it before. The last section of my novel Refuge is entirely taken up with mould. The elderly Cass and the young Burmese refugee Nang share an obsession with trapping life in an image, and when Nang discovers Cass’s box of old negatives in a shed, the celluloid eaten by moulds, she embarks on a project to breed colonies on her own photographs, using the fungal filaments of microscopic creatures to shape life into art. For months, I delighted in the complexity, the diversity, the persistence of mould. How can I despise it now?

The mountain of mould-colonized books at our backs grows as the shelves empty. The few thin volumes that Wayne set on the mantle have splayed their pages, turning pink now from the spores that cloud the air. We add these books to the heap, too.

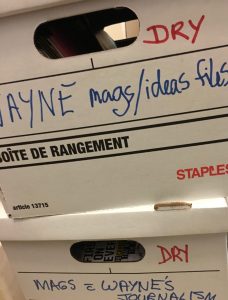

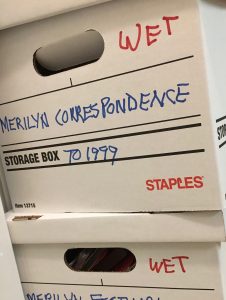

We must press on. Furniture needs pitching. Paintings need assessing. Boxes of dripping archives need sorting. The photograph albums, with their own bloom of mould, await. The sodden mess of our life must be gone through, triaged, reshaped into a reduced mosaic of things.

We must press on. Furniture needs pitching. Paintings need assessing. Boxes of dripping archives need sorting. The photograph albums, with their own bloom of mould, await. The sodden mess of our life must be gone through, triaged, reshaped into a reduced mosaic of things.

“They’re just things,” our friends say, trying to boost our spirits. But it’s not the thingness of the objects we mourn, it is the stories they sparked in us.

The books came first, and as always, they prove our best guide. Stories are indestructible. Perhaps not with joy, but at least with less despair, we step deeper into our disintegrating material world, certain we can salvage what neither water nor mould can obliterate.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

What books have you lost that you still carry with you?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Comments

This has knocked the breath out of me, Merilyn. So moving. And so beautiful. (“… his voice sharp with the kind of hope that knifes up from despair.”)

I am thinking about your question. Richard’s antique family bible was harmed (but not ruined) by water from a broken pipe. I lost some research books to mould last winter in Mexico, but I was ready to let them go. I’m almost superstitiously afraid to mention such good fortune.

Oh, Merilyn, I’m so sorry to hear this — and yet, this is such a beautiful post. Sending love to you and Wayne.

Oh dear. Oh… a lovely post, but such loss. Water…floods. We lost so much in Calgary’s flood. An entire basement. But not one book. We were spared that. And really… that might equate to no loss. So sad for you and grateful for your sharing.

Merilyn: i think your post should be Buddhist manifesto on how to release attachments, or turned into a TED talk.

Seriously…

I borrowed a book from my printmaking professor. It was a “Guide to Handpapermaking.” Years went by. I never returned it. I kept the book in a box. The lid covered my guilt. When the mould stole this book from me, I felt relief. Mould, it seems, is not always a bad thing.

And, I’m serious about the TED talk. Your ordeal, and how you and Wayne are processing this, can speak to the essence of our human condition”ing.” There is a modern world clinging to something. Certainly that’s why I suffer. The technique of labeling what is lost (metaphorically) and what might be saved seems to suggest a comfort I had never considered.

Thank you for the post…

Book lover’s worst nightmare so gently, lovingly, recounted. I am sorry.

This really touched me. Over twenty years ago, in another house, my entire basement was flooded. It had been filled with boxes of treasures (books, records, journals) from my parents that I planned to go through one day. I remember seeing everything floating on the two feet of water that turned the basement into a swimming pool. It took months to sort and all of it had to be tossed. Your story brought back that smell, the documenting, the loss.

This same conversation came up recently too with my friends from Fort McMurray who were saying how, since losing their homes to fire, there are days they forget and still reach for treasured possessions that are long gone. One of them has written a book about her experiences – and the painful choices you have to make when you are given twenty minutes to retrieve your most valuable items from a home about to burn to the ground. (She grabbed the family bible).

I am so, so sorry you are having to deal with this.

This is a poignant and beautiful piece Merilyn. Thank you.

By the time we reach a certain age, the losses have begun to pile up…parents, friends, siblings, pets, but beloved books is not a category we expect to add to the stack. If anything, we hope to pass these personal treasures on to our children who we have raised to be avid readers.

There is one book that I cannot pass on—Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. My son recently came across it and asked had I read it. Yes, I had. And I had underlined sections and filled white space with marginalia. Every ten years or so I would return to it and note changes in my perspective. I loaned that book to a friend who was reluctant to undergo a much needed transplant—her second. I had hoped Frankl’s words would help her find the strength to make the decision that was right for her. The surgery was successful. The book when I have asked for it to be returned is “somewhere”, and has been “somewhere” for over five years. I have purchased another, but the loss of that one with all its recorded memories is something I still grieve.

Some will say, “Get over it. It’s only a book.” But for those of us who can get lost in the other mind-space that books create will know that books become part of our personal history. Their loss becomes personal.

I read this late last night, and your books, and the two of you lovingly recording this loss, tumbled into my dreams. Thank you for writing this, Merilyn

A thoughtful piece Merilyn on what remains after a flood…. and heartened to read how you both are responding to this terrible loss.

fond regards,

Thank you, Merilyn, for diving straight to the love that makes the loss of these books so heartbreaking and for finding its odd beauty. I’ve never lost a book to water damage, though I’ve lost several by forgetting a loan to a friend. I’ll never see my copy of Ulysses again. The friend who borrowed it many years ago claims a squatter’s right to it.

An absolute nightmare. So sorry about all that is lost…an archive of a life. But you have also found beauty — in the mould and elsewhere.

Is it consoling – I hope so – to know that whatever was damaged/lost/happily moulded in the catastrophe, your writing remains eloquent and tuneful and vivid. Nothing lost there!

Oh my God! This is so much worse than our tiny basement floods. Mould — gosh, fascinating, but dangerous. My dears. I’m appalled. I have books — none that will be the precious first volumes for you, but ones I could give you. Along with my love.

Sue

(tried apparently unsuccessfully to post comment on Monday morning…) Merilyn I read this late Sunday evening, and you and Wayne and your books filtered into my dreams. Thank you for recording and recognizing your loss, but especially for writing so powerfully about it. I look at my books and bookshelves differently now. Warm regards, Marian

Merilyn, out of such an appalling loss, a beautiful blog post and a gorgeous, delicate, mould painting. There will be much to write about, and the TED talk suggested is just one possibility.

To respond to your question, although many books have left my shelves one way or another over the years, there are three that I feel the loss of still: the first was a leather bound vellum edition of Schopenhauer’s, ‘Essays in Pessimism’, (found in a second hand store in Vancouver in the early 60s) that mysteriously disappeared; then there was James Elkins, ‘Picture This’ and Simon Winchester’s, ‘Mauve’ that I may have lent out. None of these were signed, and they are all available in one form or another, but it is MY copies of these books I still miss.

Beyond books, there was a sweater, a ring, and a pair of shoes that were taken away before their time with me was up. Why these books, these items? What is so special about them as links to relationships and events that such objects create an ongoing sense of loss?

I like to think of Heaven as a place where one is reunited with lost treasures: a certain necklace, in my case, left behind in a hotel room, back before I learned not to travel with treasures. It was a collection of found objects, including an old iron key — a necklace of lost objects, so perhaps destined to be lost in turn. I can only hope that it is someone’s treasure once again.

It an effort to make it easier to give away objects I’m fond of, I’ve begun a digital photo project documenting their meaning in my life — spike heels, my last manual typewriter, a non-functioning but aesthetically eccentric pair of Japanese scissors. The impulse, I think, is to hold on as I become more aware of time (and life) passing.

There is another category I often think of adding: a digital album of treasures I would ache for were they to be lost by fire or flood. The first to grace this “pre-memorial” collection would be a photo of a book by the San Francisco poet Kenneth Patchen. I was 19, a married student, on the way to nightshift work as an elevator operator at the Mark Hopkins hotel. I stopped in a little bookstore, wanting to find a book of his poetry. The owner asked, Can I help? I told him what I was looking for. He disappeared for a moment, returning with a colourful volume. It was a limited edition, created by Patchen, his artwork as a cover. He sold it to me for pennies. I flew out of that shop, holding the book to my heart. Such a gift!