[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The spring of 1956 was slow to arrive. That April—unlike ours—was cold, with heavy snows; at the end of the month, the ice on Pimisi Bay was still solid. The spring migration seemed off-kilter to Louise. The few flyttfågar—migratory birds—that landed in her woods were five to eleven days late. The vast flocks were stalled, she assumed, somewhere to the south.

The mass of polar air hung like a lingering thought over Louise’s forest. The snow stayed crisp and deep. She watched as a flock of swallows turned in the teeth of the cold wind and headed south again. “But I do not know how far they went, perhaps only a mile or two out of the worst rage of the elements. There is a lot in nature that you only think you know because it seems logical, but things may not happen as you think they ought.”

The mass of polar air hung like a lingering thought over Louise’s forest. The snow stayed crisp and deep. She watched as a flock of swallows turned in the teeth of the cold wind and headed south again. “But I do not know how far they went, perhaps only a mile or two out of the worst rage of the elements. There is a lot in nature that you only think you know because it seems logical, but things may not happen as you think they ought.”

When Birds Fell from the Sky

Suddenly, on May 11, warm air flooded the forest; within hours, the temperature soared into summer. The buds on the trees swelled. Insects hatched. Louise watched for the birds to arrive, but the wave of migrants did not appear. They were flying high above, madly making up for lost time as they pushed farther north.

Four days later, another Arctic cold front descended overnight, shoving the temperature below zero and blanketing the ground with snow. When Louise went out for her dawn walk, the snow was dark with warblers and thrushes, flycatchers and swallows, hopping stiffly from straw to dead leaf, wallowing in the white stuff looking for food, or sitting shivering on low branches, warming their freezing feet in the soft feathers of their bellies.

Four days later, another Arctic cold front descended overnight, shoving the temperature below zero and blanketing the ground with snow. When Louise went out for her dawn walk, the snow was dark with warblers and thrushes, flycatchers and swallows, hopping stiffly from straw to dead leaf, wallowing in the white stuff looking for food, or sitting shivering on low branches, warming their freezing feet in the soft feathers of their bellies.

By noon, birds covered the roadsides and the guard rails. Still the birds came on, doggedly heading north into the teeth of a piercing wind, hugging the ground, seeking what food and shelter they could. A Ruby-throated Hummingbird, rebuffed by the wind, fell on the cold cement foundation of Louise’s house, clung there for a long miserable minute, then lifted again, hovering along her windows to disappear northward in the gathering dusk.

Uncounted masses of birds died that spring. Just as they died last August and September, hundreds of thousands falling out of the sky in a mass die-off across New Mexico, Colorado, Texas, Arizona, and Nebraska, their carcasses little more than feather and bone. A cold snap may have sent them tumbling to earth, but they were already weakened by the drought killing off the insects that sustain migrating birds.

Despite the weather, despite dwindling food supplies, despite forest fires and erupting volcanoes, birds turn south in the fall and head north again in the spring, driven by an urge that has nothing to do with logic.

Contact Tracing

Louise kept meticulous records of the first bird of each species that she saw in her woods each spring. Where I live, Ron Weir did the same. I thumb through his Birds of the Kingston Region to find out exactly when to expect our ruby-throats. Last year, I watched as one hovered in front of our house, and finding nothing to sip on, flew off to sweeter pastures. This year, I want to be ready with sustenance the moment they cross the floral wasteland that is Lake Ontario.

Ornithologists in this area have been recording hummingbirds for more than 130 years, the date of arrival hardly unchanged in all that time. The earliest arrival of the hummingbird is May 1 and the average is May 9, with peak sightings around Victoria Day weekend.

Mayday is still eleven days away, but even so, I fill the glass feeders we brought from Mexico. I set one on a spike in the front planter, hang another near the top of the apple tree, and a third just above the primula that are set to bloom. Broad-bills and violet-crowns zoom to our feeders in San Miguel de Allende, but the ruby-throats winter further south, in Oaxaca and the Yucatan. I long to see these jeweled sprites, with their memories of the jungle. Perhaps they’ll be early, lured north by our balmy weather.

The Limit of Logic

This is faulty thinking, I know. If weather is a factor in bird migration, it is not the only factor, nor even the most important. Otherwise, I wouldn’t see robins pecking helplessly at the frozen ground in March. And millions of birds would never fall from the sky, too cold or too starved to fly on.

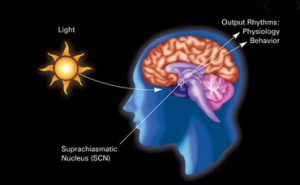

Am I subject to the same kind of irresistible, unknowable, pre-programmed urges? Of course I am. When I was desperate to have babies, I put it down to love, but it wasn’t personal, not really: I was a species intent on reproducing itself. And despite alarm clocks, workday schedules, and common sense, I wake every morning now at 5 am, just as I woke at 8 am in midwinter, my body clock neither digital nor analog but set to the rising of the sun.

Am I subject to the same kind of irresistible, unknowable, pre-programmed urges? Of course I am. When I was desperate to have babies, I put it down to love, but it wasn’t personal, not really: I was a species intent on reproducing itself. And despite alarm clocks, workday schedules, and common sense, I wake every morning now at 5 am, just as I woke at 8 am in midwinter, my body clock neither digital nor analog but set to the rising of the sun.

Bird Lesson #3

How deeply embedded, how insistent are my internal clocks? Are they simply what I think of as habits—good and bad? Can they be budged with sufficient discipline?

Every time I start a book, I think, This one will be quick. A year. Maybe less! But as I finish Woman, Watching: Louise de Kiriline Lawrence and the Birds of Pimisi Bay and start the next, still unnamed, I see that once again my cycle holds. I long to be like Faulkner, who wrote Light in August in seven months, but yet again, it is three years.

Isn’t it logical that with each book, I should get better—faster—at this writing game?

But I don’t. I am not a phoebe or a robin, which have been here for a month. I’m not even a Purple Finch or a Song Sparrow, which arrived last week. I’m like the flycatchers, slow to arrive, never among the front-runners and often among the last, although I get there just the same.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Comments

I think a big part of the stress that this pandemic has caused in us is because the restrictions have disturbed our natural rhythms. Humans are a migratory species, or at least a nomadic one. Domestication has bred a lot of that out of us, as it has of cattle and other herd animals, but somewhere buried in our DNA is the annual urge to travel, which is frustrated by stay-at-home orders and border closings. We can only move from our homes to a grocery store and back again. Is this perhaps the equivalent of what we see in caged birds, endlessly hopping back and forth from one perch to another?

It’s all true. We’re not able to go to our lake — a very big gap in our life. I’ve written a couple of poems about it, but you know, that’s not much fun, or even sense of achievement. At least now I can hear the birds singing in my back yard as I write this.