[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The white-faced ibises have disappeared. I used to climb to the rooftop terrace while the sun was splashing colour up into the dawn and watch the dark, graceful arcs of birds float across the sunrise, west to east.

Infinite Iterations

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]My husband hears draft and thinks beer. I hear draft and think breeze. We’re both writers, but when it comes to producing drafts (not beer or breezes but the scribbling kind) we are as different as two writers can be. Ask him how many drafts it takes to write a book, and he’s likely to say, “Six or eight.” I’ve never racked up fewer than fifteen. I thought my new book would be different, but here I am at ten, and my agent has just spoken those dreaded words: “It’s not ready yet.”

Nota Bene

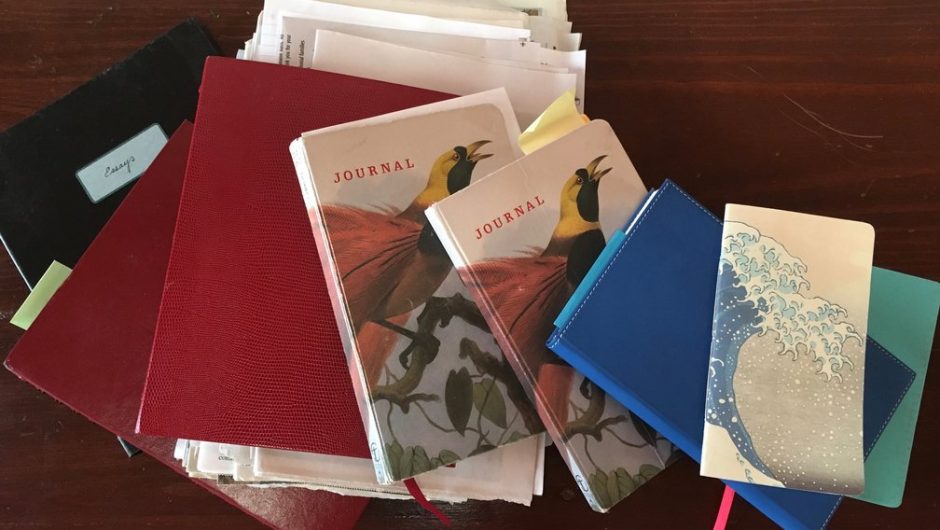

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Thomas Hardy typically had several notebooks on the go, each one carefully labelled Poetical Matter; Literary Notebook; Studies, Specimens, etc; or Facts. In Facts, Hardy and his first wife, Emma, recorded curious incidents culled from local newspapers. One three-line entry is titled “Sale of Wife”—a note that grew into The Mayor of Casterbridge.

The Cutting Edge

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] After seven years of researching and writing, I finally printed out a draft of my nonfiction novel The Convict Lover. The stack of pages was higher than a child’s booster seat. Even in my innocence, I knew prospective publishers were unlikely to read a 750-page prison tome, so I hauled out my scissors and glue pot—this was 1994, the digital dark ages—and attacked my hard-won words. Six months later, the manuscript was lean and muscular, reduced to a mere 88,000 words from its original 200,000. My heart, along with countless, priceless scenes, lay in shards on the floor.

Under the Influence

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]When Helen Keller was eleven, she wrote a story called “The Frost King.” The Perkins School for the Blind published it in their alumni magazine. Almost immediately, Helen was accused of stealing the idea from Birdie and his Fairy Friends, a book she’d never heard of. Her teacher, Anne Sullivan, discovered that someone had, in fact, read the book to Helen when she was eight, finger-spelling the words for the blind, deaf child. Helen had no memory of this. For hours, the girl was grilled by a jury of teachers. She was absolved, narrowly, but the ordeal triggered a nervous breakdown. She never wrote fiction again.

Where do Books Come From?

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] In one creation tale, from Tumblr’s

zwischendenstuehlen, books are hatched as tiny tomes — blind and naked creatures. Diligently, the writer makes little jackets to keep them warm during the first dark season of their lives. Those that make it through their various trials grow up to be big and strong and wise, taking their place on the shelf beside their older sisters and brothers.

The Unexpected Nature of Collaboration

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]In an exhibition featuring Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera at the Detroit Institute of Arts a few years ago, I found a small framed drawing in a far corner. The image was bizarre: a round-breasted woman holding a fig leaf on strings over prominent male genitalia. The title of the piece was Exquisite Corpse, the name the Surrealists gave to an old parlour game known as Consequences.

Exquisite Corpse is a kind of blind collaboration. The game begins when one person draws a head at the top of the page, then folds over the paper to conceal the image from the next person, who then draws the chest, handing the paper back and forth (or around the parlour) until the entire character is drawn and the image — often funny, always strange, and definitely accidental — is revealed.

Recent Comments