[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Yet again I forgot to move my knife to my checked luggage. “But it’s a paper knife. For cutting open the pages of a book,” I explained to the security officer bent over my carry-on.

“I don’t care what you cut with it, m’am; you aren’t taking that knife on this plane.”

The Paper Knife

The long silvery dagger is not even a real paper knife. It’s a letter-opener, which was all that Hugh and I could find.

The long silvery dagger is not even a real paper knife. It’s a letter-opener, which was all that Hugh and I could find.

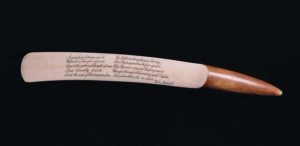

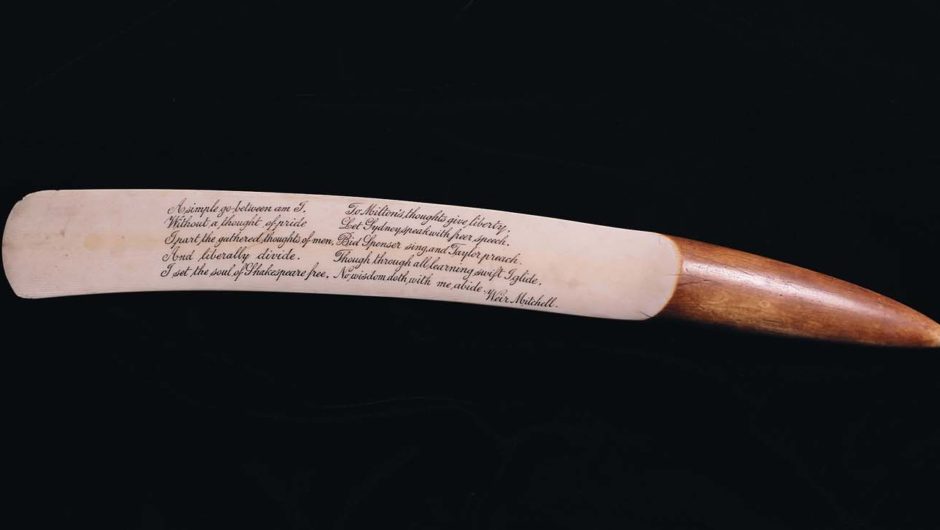

A true paper knife is a long, broad blade with a blunt tip. It looks a bit like a butter knife.The blade wasn’t intended to be sharp, which meant the knife could be made of ivory, bone, mother-of-pearl, polished exotic wood, even brass and silver. The handles were often delicately carved and painted. Some had novelty handles featuring a small magnifying glass or a telescope.or slender compartments in which to secret a pinch of snuff or precious gem. By the late 1700s, a paper knife was standard equipment on a reader’s side-table.

In the Library, with the Pen Knife

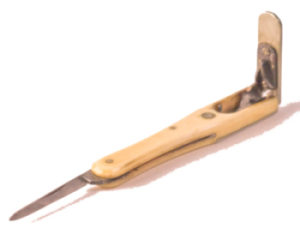

The paper knife evolved from the pen knife, used to sharpen quill nibs, which wore down quickly. A person might sharpen his nibs three or four times in the course of writing a long letter. A pen knife had a short, steel blade honed to a razor edge and a wicked point The blade was fixed into a haft; sometimes the blade could slide inside its handle.

The paper knife evolved from the pen knife, used to sharpen quill nibs, which wore down quickly. A person might sharpen his nibs three or four times in the course of writing a long letter. A pen knife had a short, steel blade honed to a razor edge and a wicked point The blade was fixed into a haft; sometimes the blade could slide inside its handle.

In Pride & Prejudice, Elizabeth watches Darcy writing to his sister. Miss Bingley offers to assist. “I am afraid you do not like your pen. Let me mend it for you. I mend pens remarkably well.”

![]() “Thank you,” says Darcy, “but I always mend my own.” He’s not being rude. Writers generally preferred to mend their own pens when the point became dull or misshapen. A little fine tuning, and the point was good as new, although eventually, the quill would have to be re-cut or thrown away.

“Thank you,” says Darcy, “but I always mend my own.” He’s not being rude. Writers generally preferred to mend their own pens when the point became dull or misshapen. A little fine tuning, and the point was good as new, although eventually, the quill would have to be re-cut or thrown away.

By the early 19th century, the pen knife had evolved into the pocket knife. The blade was hinged to the haft and the two could be folded together so they could be carried in the pocket.

The Unopened Book

“Wouldn’t it be nice to have uncut pages?” I mused to Hugh Barclay as we planned the letterpress edition of my book of stories, The Paradise Project.

“Wouldn’t it be nice to have uncut pages?” I mused to Hugh Barclay as we planned the letterpress edition of my book of stories, The Paradise Project.

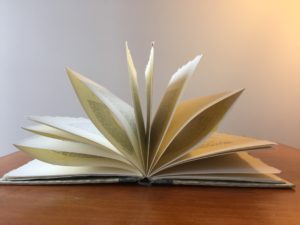

I was using the term incorrectly. After paper became widely available in Europe, printing technology rapidly advanced. Paper-folding and trimming machines were invented to cut the ragged fore-edges of a book. Occasionally, the trimmers missed a folded page. These “uncut” pages were accidental, a delight or an irritation, depending on the temperament of the reader.

What I should have said was “unopened,” known in the book trade as intonso. Not an accident at all. Before mechanical folders and trimmers, books were either trimmed by hand or sold with all folded pages unopened. Readers would pull out their pen knife or the small erasing knife they used to scratch their inky mistakes off the page. But slitting the fold to release the story wasn’t easy. The short, sharp blades of the pen knife left the pages jagged and torn, and the sharp tip was likely to jab into the fibres.

Some brilliant reader, lost to history, discovered that a long, smooth blade with a rounded tip, when inserted with firm pressure into the fold, would cause the paper fibres to neatly give way, especially if the flat of the knife was used first to sharpen the fold. And so the paper knife was born.

In the Study with the Letter-Opener

Hugh loved the idea, even though it meant that the print run would require him to make 14,000 folds by hand. If we were selling a book with pages unopened, we should supply a paper knife, he said. How, then, to attach the knife to the book? A book sleeve, of course. And how would a book buyer know what to do with it? Include instructions, what else?

Hugh loved the idea, even though it meant that the print run would require him to make 14,000 folds by hand. If we were selling a book with pages unopened, we should supply a paper knife, he said. How, then, to attach the knife to the book? A book sleeve, of course. And how would a book buyer know what to do with it? Include instructions, what else?

“I can see it all quite clearly,” Hugh said.

By the late 19th century, books were trimmed by machine, and the gummed envelope had been invented. No longer needed for books, the paper knife morphed into a new writing-desk accessory: the letter-opener. The blade became narrower and sharper.

One of the most famous letter-openers belonged to Charles Dickens. The ivory blade is engraved “C.D. In Memory of Bob 1862″ and it is topped with the stuffed paw of his cat. His daughter Mamie in her memoir, My Father as I Recall Him, writes that the cat, “who was quite deaf, became known by servants as “The Master’s Cat,” because of his devotion to my father. He was always with him, and used to follow him about the garden like a dog, and sit with him while he wrote.”

I looked everywhere for a paper knife for our Paradise Project. I found none, not even on eBay. Finally, I bought three hundred silvery letter-openers from the local office-supply store.

When Hugh and I launched The Paradise Project, we invited friends to a garden party. Some of those who bought books sat hunched on the grass, slicing open the pages with the paper-knife-that-is-really-a-letter-opener. Others looked on aghast, hugging their books to their chests, vowing to release each story as they read. One bought two copies: one to open and one to leave uncut.

I often think of that unopened book, its stories forever trapped, waiting for someone with a paper knife to release them into the world.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

What is in your book lover’s arsenal?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Comments

I remember buying French books from presses like Gallimard that were unopened. Sometimes in used bookstores. One of the pleasures of opening the pages as I read was the certainty that I was the first person to have read that book.

I love that feeling of being in uncharted territory, too, Wayne. The problem is that when I order old out-of-print books on-line and they arrive uncut, I can hardly bring myself to slice the pages.

A further note: the English word “pen” comes from the Old French “pene,” meaning “feather,” or “quill,” which in turn comes from the Latin “penne”, meaning quill. In French, a “pen” is “plume,” so the sense of a writing implement deriving from the feather of a bird is retained in both languages.