[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]When Buenos Aires was the World Book Capital in 2011, the city constructed an 82-foot, wire-mesh tower that entrapped 30,000 used books donated by libraries, embassies, and individuals. Visitors climbed stairs inside the “Tower of Babel,” reading the titles and listening to Marta Minujín, the installation artist who conceived the project, repeating the word “book” in dozens of languages.

My first reaction was, Wow, books as public art! Followed by, Yikes! The destruction of so many books!

My first reaction was, Wow, books as public art! Followed by, Yikes! The destruction of so many books!

I needn’t have worried. Each book was wrapped in plastic. The Tower of Babel stood for three weeks in a main square, and at the end, visitors were encouraged to take a book home. What remained would become the basis of a new book archive, the Library of Babel, named for a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, Argentina’s most famous literary son.

The Book as Freedom of Expression

Marta Minujín had done this before. In December 1983, a week after the restoration of democracy in Argentina, she created a Parthenon of Books, built of books banned during the military dictatorship.

And now she is doing it again, this time on a grand scale in Kassel, Germany. 100,000 books for this new Parthenon were donated by the public from a shortlist of over 170 titles of banned books, some of them still on public must-not-read lists.

And now she is doing it again, this time on a grand scale in Kassel, Germany. 100,000 books for this new Parthenon were donated by the public from a shortlist of over 170 titles of banned books, some of them still on public must-not-read lists.

The new Parthenon was erected this spring in Friedrichsplatz Park, where 2,000 books were burned 84 years ago by the Nazis. The Buenos Aires Parthenon of Books was eventually tipped over by two cranes to allow the public to take the books they wanted. The same will happen in Kassel.

The Book as Destruction

A more permanent monument to books is installed on Berlin’s Bebelplatz, the square that was the site of the most infamous of the Nazi book-burnings of May 10, 1933. For days, students dragged the contents of the Institute for Sexual Science library into the square, where some 20,000 books were burned.

A more permanent monument to books is installed on Berlin’s Bebelplatz, the square that was the site of the most infamous of the Nazi book-burnings of May 10, 1933. For days, students dragged the contents of the Institute for Sexual Science library into the square, where some 20,000 books were burned.

The 1995 memorial created by Micha Ullman consists of a glass plate set into the cobblestones to give an eerie view into a subterranean room of empty bookcases, enough to hold all 20,000 burned books. Nearby, a plaque quotes Heinrich Heine from his prescient 1821 play, Almansor: “Where they burn books, they  will in the end also burn people.”

will in the end also burn people.”

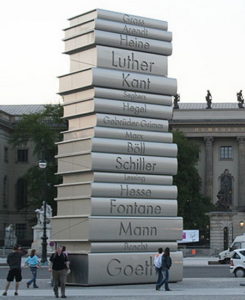

At the edge of Bebelplatz is Buchdruck, a 2006 book sculpture that commemorates modern printing with a 12-metre stack of books weighing 35 tons. The spines are carved with the names of significant German writers from Goethe through Hesse, Boll, Marx, and Grass to the Brothers Grimm and Hannah Arendt, the only woman represented.

The Book as Reconciliation

Books have become almost iconic of the Second World War, appearing in many Holocaust memorials, and as a key element in the work of post-war artists such as Anselm Kiefer—often with gigantic pages, tattered and defaced, their surfaces covered with ash.

But British artist Diana Bell used books to convey reconciliation. The sculpture was commissioned as a thank-you from the city of Bonn, Germany, to Oxford, England, the first municipality to approach a German city after the war in a gesture of friendship and common concern.

But British artist Diana Bell used books to convey reconciliation. The sculpture was commissioned as a thank-you from the city of Bonn, Germany, to Oxford, England, the first municipality to approach a German city after the war in a gesture of friendship and common concern.

These bronze books are cast from real books and arranged in stacks around a town square, with small piles on benches, too, where people can interact with them. The spines are chiselled not with the names of actual books but with the optimistic titles: Knowledge, Understanding, Friendship, Trust, Wissen, Verständigung, Freundschaft, Vertrauen.

A nearby plaque writes the word Peace in Arabic, Hebrew, Sanskrit, and English. “To honour those who seek another path in place of violence and war.”

The Language of Book

grāmata (Latvian)

grāmata (Latvian)

książka (Polish )

Llyfr (Welsh)

בוך (Yiddish)

kirja (Finnish)

raamat (Estonian)

llibre (Catalan)

kitab (Azerbaijani)

书 (Chinese)

പുസ്തകം (Malaysian)

Sách (Vietnamese)

کتاب (Persian)

Buug (Somali)

ibhuku (Zulu)

aklat (Filipino)

libro (Esperanto)

Books, Books, Everywhere Books

Two children sit atop a tower of books balanced on a globe outside the Bangkok Arts & Cultural Centre.

An enormous book spreads its pages on the University Embankment in St. Petersburg, Russia.

An enormous book spreads its pages on the University Embankment in St. Petersburg, Russia.

A “Book of 98 Patriots” stands open in Erbil, Kurdistan, in Sami Abdulrahman Park, built on the site of Saddam Hussein’s former military base and detention camp. It lists the names of almost a hundred people killed in a 2004 terrorist attack.

A pavilion outside the Cheongju Art Centre in South Korea is in the shape of a giant butterflied book about to be set on the ground, a memorial to the Jikji, a book printed with a version of movable type seventy years before Gutenberg.

A pavilion outside the Cheongju Art Centre in South Korea is in the shape of a giant butterflied book about to be set on the ground, a memorial to the Jikji, a book printed with a version of movable type seventy years before Gutenberg.

A statue in Sevilla, Spain, honours of a young girl reading honors Clara Campoamor and her contribution to women’s freedom.

The House of Creativity in Turkmenistan is a multi-storeyed building with an open book as its facade.

The House of Creativity in Turkmenistan is a multi-storeyed building with an open book as its facade.

This year UNESCO has declared Conarky in the Republic of Guinea, West Africa, as the World Book Capital. Next year, it is Athens, Greece. One wonders what bookish monuments they will build.

The Meaning of Book

No one will ever turn the pages of these bronze and concrete books. Most don’t have pages to turn, or words to read. Ironically, these books need no words to convey their message

The book—this handheld collection of pages bound on one side—has become a universal symbol. In this sense, it doesn’t matter what is written inside. A book is knowledge. A book is creativity. A book is freedom. A book is memory. A book is redemption.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

Have you seen any great public book-art?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Comments

The tower of books in Berlin’s Bebelplatz is interesting as a work of literary criticism, too: poor thin Brecht squeezed between two giant books by Goethe and Mann. And is Heinrich Böll really weightier than Karl Marx?

The arrangement is curious. Who decided, I wonder? It’s not alphabetical, it’s not chronological. I’m not sure it’s aesthetic. But I like that Hannah Arendt is (almost) on top!