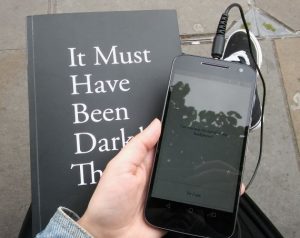

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Imagine listening to Maggie deVries’ Rabbit Ears in Vancouver’s downtown east side, among the runaways, addicts, and women of the street she portrays. Or any David Adams Richards book while walking the shore of the broad Miramichi. Or canoeing north of Yellowknife in the company of Liz Hay’s Late Nights on Air. Now imagine a story written to take you to a specific place, where what you see and hear and smell dives you deep, deep, deep into the words. That’s ambient literature.

You Have To Be There

Listen to Famous Blue Raincoat or hang out at a Leonard Cohen concert. Read Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf or get close to the stage.

Being there is better, partly because it involves more than the sense of sight. It’s feeling the spit fly from the actor’s mouth, hearing the cheers and sighs of fans around you, smelling the tortillas. It is being so immersed in the art that you feel it not only with your heart and your mind but in every cell of your body, too.

Ambient literature. Locative literature. Situated literary experience. Walking books. There’s no good name for this new baby yet, but it is growing at a rapid rate. Unlike an ebook, which is little more than a paper book repurposed to a screen, this new breed of digital storytelling makes use of the technology we already have in our smartphones—internet access and GPS.

Location, Location, Location

Time and place: a story can’t exist without them. It’s the setting that transports a reader to the writer’s world. And setting is not only geography: it creates the tone, establishes the time. Sometimes setting is a character. Think Wuthering Heights. Or All the Light We Cannot See.

Time and place: a story can’t exist without them. It’s the setting that transports a reader to the writer’s world. And setting is not only geography: it creates the tone, establishes the time. Sometimes setting is a character. Think Wuthering Heights. Or All the Light We Cannot See.

Ambient literature shares all the usual elements of a good story—character, plot, narrative arc—but its roots twine also into oral storytelling, serialized fiction, and walking tours.

There’s nothing new here, really. People have been telling each other stories as they walk for as long as we’ve been ambulatory. Long before Chaucer, pilgrims entertained themselves with storytelling contests. And what are the stories recited at the Stations of the Cross but an audible book told in situ?

Literary walking tours have been giving meaning to cityscapes for decades. Rebustours, for instance, offers a “Secret Edinburgh” tour that combines Ian Rankin’s detective with readings from the works of famous Scots such as Arthur Conan Doyle and Robert Louis Stevenson. There’s hardly a major city without a Ghost Walk that takes visitors from one haunted locale to another, telling the story of its haunting. And audio tours have become a staple of museums, art galleries, even prisons like Alcatraz. At the end of the month, I’ll be leading one of my own: a “Prisoner’s Walk” through Portsmouth village, reading from The Convict Lover in the places where the action unfolds.

Literary walking tours have been giving meaning to cityscapes for decades. Rebustours, for instance, offers a “Secret Edinburgh” tour that combines Ian Rankin’s detective with readings from the works of famous Scots such as Arthur Conan Doyle and Robert Louis Stevenson. There’s hardly a major city without a Ghost Walk that takes visitors from one haunted locale to another, telling the story of its haunting. And audio tours have become a staple of museums, art galleries, even prisons like Alcatraz. At the end of the month, I’ll be leading one of my own: a “Prisoner’s Walk” through Portsmouth village, reading from The Convict Lover in the places where the action unfolds.

Pervasive Computing Platforms

Locative literature goes further. It digitally connects the story that appears in words on your phone or tablet to the place where you are. You aren’t only reading a book, you are moving physically through the landscape of the book.

Locative literature goes further. It digitally connects the story that appears in words on your phone or tablet to the place where you are. You aren’t only reading a book, you are moving physically through the landscape of the book.

In Reif Larsen’s Entrances & Exits, offered by Visual Editions, the text of the story is tucked behind doors in a Google Street View map.

Eli Horowitz expanded the concept over continents. The Silent History is a complex novel that imagines a generation of children who are unable to read or write. The $3 iOS app is loaded with 120 testimonials from characters directly affected by the condition—parents, teachers, faith healers—and connects to Field Reports, short, site-specific accounts that expand the central narrative. To trigger a Field Report, the reader has to stand in the exact location where the Report is set—Manhattan, Chicago, Berlin. The format is tricky to get the hang of and each element can be read on its own, but once you get into it, the elements fuse into a gipping narrative that is much greater than its parts.

Sticky Stories

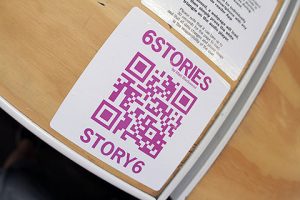

Matt Blackwood, an inventive Australian writer, has been experimenting with location literature for years. One of his first was 1Story, now expanded to 6, in which a story is activated by scanning a QR code. (You have to be in Australia!)

Matt Blackwood, an inventive Australian writer, has been experimenting with location literature for years. One of his first was 1Story, now expanded to 6, in which a story is activated by scanning a QR code. (You have to be in Australia!)

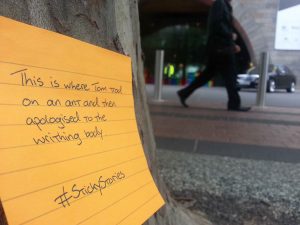

For Blackwood, location literature doesn’t have to be digital. He has plastered his hometown of Melbourne (a Unesco City of Literature) with stories written on sticky notes, spelled out in Scrabble tiles, embossed into heavy label tape, writ large on billboards, or pressed into felt board and held up in the places where the stories unfold.

For Blackwood, location literature doesn’t have to be digital. He has plastered his hometown of Melbourne (a Unesco City of Literature) with stories written on sticky notes, spelled out in Scrabble tiles, embossed into heavy label tape, writ large on billboards, or pressed into felt board and held up in the places where the stories unfold.

“Let’s take our private love of books,” says Blackwood, “and make it public.”

From ambient literature to civic literature.

Stories R Us

Digital technology not only takes us to the action, it can turn a book on its head, transforming readers into writing collaborators.

[Murmur] records people’s stories of a place—the stories that make up a city’s identity, but that exist mostly inside of the heads of those who live there. They install a [murmur] sign with a telephone number that you can call to listen to the stories while standing in that exact place. Some stories suggest the listener follow a certain path; others encourage wandering. Launched in Toronto in 2003, [murmur] has spread to Vancouver, Montreal, Edinburgh, Dublin, and Australia’s Geelong.

[Murmur] records people’s stories of a place—the stories that make up a city’s identity, but that exist mostly inside of the heads of those who live there. They install a [murmur] sign with a telephone number that you can call to listen to the stories while standing in that exact place. Some stories suggest the listener follow a certain path; others encourage wandering. Launched in Toronto in 2003, [murmur] has spread to Vancouver, Montreal, Edinburgh, Dublin, and Australia’s Geelong.

In Australia, the Story City project creates serialized, choose-your-own-adventure type stories that take place in real settings in Brisbane, Adelaide, and the Gold Coast. The Story City app is free to download on a smart phone or tablet. Each story starts at a particular location, then branches off in dozens of directions, all within walking distance. When the app detects you are in the right location, it unlocks the next part of the story.

In Australia, the Story City project creates serialized, choose-your-own-adventure type stories that take place in real settings in Brisbane, Adelaide, and the Gold Coast. The Story City app is free to download on a smart phone or tablet. Each story starts at a particular location, then branches off in dozens of directions, all within walking distance. When the app detects you are in the right location, it unlocks the next part of the story.

Books That Move You

Most locative literature features maps or cues that get the “reader” moving to the next site. “Reading” becomes an athletic exercise as well as an exercise for the brain.

Read isn’t the right word. Participate is more like it.

If these loca-lit stories sound a bit like games, they are. As books, they occupy a space somewhere between novels and board games, between drama and travel, between geocaching and role-playing.

They are experiential. Ephemeral, in the way the best theatre is. Fleeting, but not insignificant. And as with any good book, at the heart is a compelling story.

It’s true, loca-lit demands a different kind of engagement, but in return, it offers a richness of experience that is hard to find reading a traditional two-dimensional book.

The Other Side of the Story

There are downsides, of course. Just as with movies and television that subvert a setting for their own purposes, ambient literature can plunder or ignore the history, politics, and social issues inherent in a place, changing it forever in the minds of readers.

And some readers will never want to give up the private joys of curling up with a good book.

But audio books are the fastest-growing shelf in the virtual bookstore, increasing by 30-40 percent a year. It is only a short leap from audio to ambient, from a book that talks—to a book that walks and talks.

Do we have to choose? Do we risk losing one by dabbling in the other? Matt Blackwood doesn’t think so.

Do we have to choose? Do we risk losing one by dabbling in the other? Matt Blackwood doesn’t think so.

As he notes, the death knell of literature as we know it has been ringing for decades.

I used to think the novel wasn’t dead, it was just pretending.

Now I think: The novel isn’t dead, it has spawned some brilliant, rambunctious kids.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

Do you “read” audio books? Have you tried ambient lit?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Comments

So interesting!

I love the idea.

Merilyn, this is marvellous and with endless applications. Lately I’ve been thinking about the vitality of a sense of place in writing. Involving the senses in every way possible… connecting the reader. Thanks so much for this.

My brain is exploding with ideas for a local writer’s festival. Ambient literature could bring this festival and literature out into the community in a meaningful way. Thank you for posting this!!

I’m so happy to hear this positive response! I could hardly sleep last night thinking of all we could do here in my community with loca-local-lit. Are we creating a new genre? Maybe!