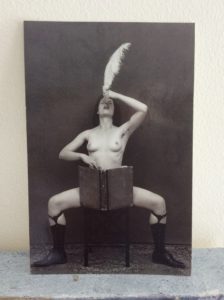

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]In the photograph, the woman is naked except for manly black brogues and argyle socks held up by leather sock suspenders. She sits splay-legged on a stool. An antiquarian book the size of a ledger is propped open between her legs. With one hand, she turns a page. In the other she holds a long feathered quill. Her eyes are closed in ecstasy and her head tips back as she dips the pen deep into her wide open mouth.

This photograph, taken by Ottawa photographer Dianne Whelan, sits on my desk and has done so through three houses and almost as many decades. I keep this photograph close because it reminds me that writing is visceral. That it only works if I stand exposed and vulnerable before the page.

This photograph, taken by Ottawa photographer Dianne Whelan, sits on my desk and has done so through three houses and almost as many decades. I keep this photograph close because it reminds me that writing is visceral. That it only works if I stand exposed and vulnerable before the page.

T. S. Eliot, it seems, agreed: “The purpose of literature is to turn blood into ink.”

Hemingway supposedly said something similar—Writing is easy. You just open a vein and bleed—except that the quote actually comes from sports columnist “Red” Smith, who, when asked if he found it difficult to churn out a piece day after day, replied, “Why, no. You simply sit down at the typewriter, open your veins, and bleed.”

Even then, it wasn’t a new idea. Nietzsche, in Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, published in the 1880s, makes a similar allusion:

“Of all that is written I love only what a man has written with his blood.” I choose to believe he meant women, too.

Rednecks

Ever since people have had names to sign, they’ve been dipping into their actual life-blood to swear undying love and loyalty. The Scottish Covenanters signed their call for a Presbyterian Scotland in their own blood, wearing red neckerchiefs as proof— the genesis of the term redneck.

But I don’t know of anyone who has taken the metaphor as far as Dutch writer Ruud Linssen, who printed his Book of War, Mortification and Love in ink made from his own blood. First, he had his blood tested “to avoid innocent people getting exotic diseases by reading a book.”

But I don’t know of anyone who has taken the metaphor as far as Dutch writer Ruud Linssen, who printed his Book of War, Mortification and Love in ink made from his own blood. First, he had his blood tested “to avoid innocent people getting exotic diseases by reading a book.”

When his blood was declared fit, vials of it were removed by a doctor and passed to a printer. Months of experimentation followed in an attempt to overcome the primary obstacle: the blood, which is water-based, refused to mix with the oil-based printing ink. In the end, Linssen’s blood was freeze-dried and lyophilized to remove every last drop of water, leaving behind a pure blood powder that was mixed with oil to create ink for the press.

Paper Skins

Writing with a nib dipped in blood seems mild stacked against the two thousand years we read pages made from parchment—the untanned skins of animals, mostly sheep, calves, and goats. Vellum was a silkier parchment made from the skins of young animals: kids, lambs, and calves. The very finest vellum was taken from unborn or stillborn calves.

Writing with a nib dipped in blood seems mild stacked against the two thousand years we read pages made from parchment—the untanned skins of animals, mostly sheep, calves, and goats. Vellum was a silkier parchment made from the skins of young animals: kids, lambs, and calves. The very finest vellum was taken from unborn or stillborn calves.

For a short while, when printing was first introduced, parchment and paper were both used, although paper made from rags was so much cheaper it quickly pushed animal membrane into a specialty niche. Then rags grew scarce and a young Nova Scotia logger and poet named Charles Fenerty proposed a solution: Why not make paper out of wood?

“I entertain an opinion that our common forest trees, either hard or soft wood, but more especially the fir, spruce, or poplar, on account of the fibrous quality of their wood, might easily be reduced by a chafing machine, and manufactured into paper of the finest kind,” he wrote in 1844. Fenerty never applied for a patent but a German mechanic, Friedrich Gottlob Keller, developed a pulping machine that changed forever the substance that carried the words we read—and reduced our living forests to mush.

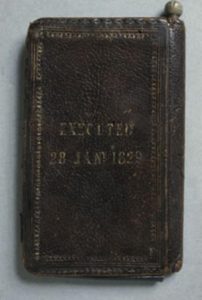

Anthropodermic Bibliopegy

As strange and disturbing as it seems, human skin has also been used, not for pages, but to bind books.

Harvard University library, for instance, has a copy of Des Destinées de l’Ame (Destinies of the Soul), by the 19th century French novelist and poet Arsène Houssaye. The author gave the book to a doctor friend, who had it bound in the skin of an unclaimed female mental patient who died of natural causes. “A book about the human soul,” wrote the doctor, “deserved to have a human covering.”

Harvard University library, for instance, has a copy of Des Destinées de l’Ame (Destinies of the Soul), by the 19th century French novelist and poet Arsène Houssaye. The author gave the book to a doctor friend, who had it bound in the skin of an unclaimed female mental patient who died of natural causes. “A book about the human soul,” wrote the doctor, “deserved to have a human covering.”

In the UK, the Bristol Record Office has a book bound in the skin of the first man to be hanged at Bristol Gaol, 18-year-old John Horwood. And he wasn’t the only murderer whose body was given to science and whose skin ended up at the tanner’s and the bookbinder’s. The practice of binding books in human skin dates at least to the 16th century and was once somewhat common, according to a Harvard blog on the Houssaye book. Although it strikes us now as macabre, individuals would ask to be memorialized, even honoured, in the form of a book covered in their skin.

Material Worlds

All of which makes me wonder about the material selves of the books in my library. Until the last century, the glues and sizings in the bindings of many, if not most, books were made by boiling down animal carcasses.

All of which makes me wonder about the material selves of the books in my library. Until the last century, the glues and sizings in the bindings of many, if not most, books were made by boiling down animal carcasses.

That’s unpleasant enough, but imagine the horror of a Hindi receiving from the hands of a well-meaning missionary, a Bible bound in calfskin.

My own first Bible, given to me by Baptist missionaries in Brazil as a prize for reading every chapter from Genesis to Revelations, is bound in white leather. I used to find it quite beautiful. Now it makes me pause.

Surely T.S. Eliot didn’t mean that literature required an actual alchemy of blood into ink. And when I said that writing, for me, is visceral, I didn’t mean that my words should be pressed onto the organ-skins of animals, or bound between covers of human skin. The idea fills me with horror.

I turn to my plastic ereader with relief. Then I wonder: are pages made from ancient fossil fuels any better? Centuries from now, will this plastic display seem just as deplorable? Perhaps by then—dare we hope—people will be reading words on some page-substitute that has no connection whatsoever to the death of living things.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477364431886{padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #ededed !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;border-radius: 2px !important;}”]

Do you know what your books are made of?

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Comments

Wonder what they did from the skin taken from the BodyWorld exhibits? Hummm….

A research project—but not for me!

Beautifully thoughtful and fascinating post. Thank you.

According to TopTenz, the most recent book bound with human skin was published in 1972 — a book of erotic Spanish poetry. The first was an account of the Gunpowder Plot conspiracy, published in 1606. A macabre history.