(Click on an image to read a ‘story behind the story’)

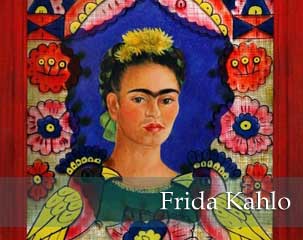

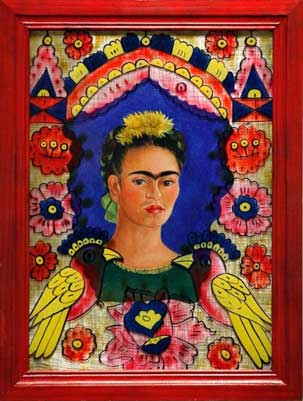

Refuge began 14 years ago with a line that jumped out at me from Hayden Herrera’s (www.amazon.ca/Frida-Biography-Kahlo-Hayden-Herrera/dp/0060085894) biography of Frida Kahlo. I can no longer find the exact phrase, but it was something like “Frida had many nurse-companions.”

Of course she did! I grew up among nurses and knew from family stories that in the early part of the twentieth century, most nurses did not work on hospital wards but became practical nurses, caring for the sick and convalescing in their homes.

I already knew the basics of Frida’s story: the terrible trolley accident when she was 18; the long convalescence and lifetime of operations (32!) to correct the damage. Like many others, I was drawn to her not only for her strange and wonderful paintings but for the chronic pain that I knew she must have suffered.

Frida never describes her nurse-companions, so I created one for her: Cassandra MacCallum, a young Canadian in search of independence and adventure. It wasn’t unusual for Canadians to travel to Mexico in the 1920s. Canadians entrepreneurs had been there for years. In fact, the trolley in which Frida was injured in all likelihood was part of the Canadian-owned Mexico Tramways Company.

You will notice that I spell her name Frida, which is the name her parents gave her and that she used, even on her paintings, until the mid 1930s, when she changed it to Frieda, perhaps to emphasize “fried,” a derivation of the German word for peace (frieden).

Today some 6,000 Canadians live year-round in Mexico, and thousands more make that beautiful country their winter home—myself included. In researching Canadians in Mexico, I discovered that 3,000 Mennonites migrated from Manitoba to Chihuahua and Durango in 1922, in search of a place where they could educate their children as they wished. Thus, Helen Klassen was born in my imagination, a Mennonite nursing student who lures Cass south.

When Frida died, Diego Rivera inherited her papers and when he died, some of that valuable archive went to his family who still live in the state of Guanajuato where Diego was born and where I spend each year December to May. My friend Sandra Gulland arranged for me to view some of these letters and papers. Seeing those impassioned scrawls up close became one of the driving forces of the story that became Refuge.

I first met Cass as a crusty old woman sitting on her island, waiting. It was years before I understood that she wasn’t waiting for her life to end, she was waiting for Nang Aung Myaing, a young Burmese woman who claimed to be her great-granddaughter.

The story of Cass’s son Charlie and his years in Burma was a long time coming. Cass did not give it up easily. He was just 14 when he ran away to the Second World War. That may seem young, but he wasn’t the only boy-soldier in that war.

Charlie was part of the 435 Squadron of the RCAF, working ground crew for the Dakotas that dropped supplies to the “ghost army” moving through the jungle, fighting to take the British colony back from the Japanese. He was also a kicker, one of the guys who physically booted the boxes, barrels, and sacks out of the cargo bag into the jungle below.

The planes flew in all weather, even through monsoons. I imagined his plane going down in a storm, lost forever in the uncharted hills of Shan State.

Long after that part of the story was written, I discovered a newspaper story from 1997, when the wreckage of a Second World War aircraft had been found in the jungle of northwest Burma. The plane had left the air base on June 21, 1945 to drop supplies to the British and went down, caught in a monsoon cloud with a shear force that could lift a loaded Dakota straight up at a speed of 6000 feet per minute and a second later, force it down at the same speed. Six young men died, two of them from eastern Ontario where I live. Reality confirmed what I had imagined.

In researching the Burma campaign of the Second World War, I came across the surprising fact that the grandchildren of veterans, regardless of where they were born, are considered Canadian citizens—and the even more surprising fact that only “pure” Burmese—those with two Burmese-born parents and grandparents—can be citizens of that country.

This led me to the plight of stateless people, who, although they may have been born in the country where they live, can be denied education, medical care, employment, permission to travel, etc. Without the usual protections of citizenship, they are vulnerable to persecution, detention, and exile.

The statistics are astonishing. Every ten minutes, somewhere in the world, a child is born into statelessness. Globally, an estimated 10 million people are stateless — and probably many more, since the stateless, almost by definition, are uncounted.

Most stateless people have been living for generations in a country, yet they have never been recognized as citizens. Others have lost their citizenship to discriminatory laws that target people on the basis of their race, religion, or ethnicity or which denies them the right to retain their nationality if they marry a foreigner.

40% of the world’s stateless are in the Asia Pacific region. Many are in Burma, where citizenship requires that both parents be Burmese citizens. Before long, Nang Aung Myaing emerged from the shadows, a young woman caught in the political mill, denied citizenship in her own country and refugee status when she finally makes her way to the country of her grandfather, the man who robbed her of her citizenship in the first place.

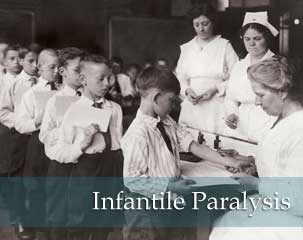

Infantile paralysis—polio—terrified parents through the first half of the twentieth century. Highly infectious, the virus blossomed in the warm summer months, sweeping through North America in pandemics that killed thousands and left hundreds of thousands crippled. Children were especially vulnerable.

I knew polio from standing in line and having my arm pricked by the school nurse. But I had no idea what a devastating disease I was being saved from until I thumbed through my great-aunt Mabel’s scrapbook of medical oddities. Aunt Mabel trained and practised in Detroit; when she died in 1973, her nursing texts and scrapbooks came to me. Among the clippings of odd cures and remedies, was a one-inch square item from an unnamed newspaper:

Dr. Maurice Brodie has received shipment of 4,000 rhesus monkeys at the harbour of New York.

What, I wondered, would anyone want with 4,000 rhesus monkeys? The question led me to an unsung hero of Canadian medical history—Maurice Brodie—a young Montreal doctor who developed a polio vaccine while working at New York’s Willard Park Hospital for communicable diseases. In the race to find a vaccine, doctors in the 1930s tested their new finds on children, sometimes with disastrous results. The human trials were stopped, but Maurice Brodie’s work went on to become the basis of the Salk vaccine that by 1994 had eradicated polio from North America.

Maurice Brodie’s story touched me deeply. In the novel, Cass MacCallum becomes his nurse, and although their relationship and his character are my invention, the facts of his life and death and the polio terror that drove families in the 1930s are all too true.

(Click on the icon below to find discussion starters.)

Want advance notice of new publications and more? Sign up for LITBITS »

Published by: ECW Press

Publish Date: September 4, 2018

Order now from your local independent bookseller or from:

Goodreads 4/5

Amazon.ca 5/5

Amazon.com 4/5

Order in German:

After a life that rubbed up against the century’s great events in New York City, Mexico, and Montreal, 96-year-old Cassandra MacCallum is surviving well enough, alone on her island, when a young Burmese woman contacts her, claiming to be kin. Curiosity, loneliness, and a slender filament of hope prompts the old woman to accept a visit. But Nang’s story of torture and flight provokes memories in Cass that peel back, layer by layer, the events that brought her to this moment – and forces her, against her will, to confront the tragedy she has refused for half a century. What does she owe this girl, who claims to be stateless because of her MacCallum blood? Drawn, despite herself, into Nang’s search for refuge, Cass struggles to accept the past and find a way into whatever future remains to her.

Hal Wake, esteemed Canadian literary maven (former CBC book producer and artistic director of Vancouver International Writers Festival), interviews Merilyn Simonds about the inspiration for and process of writing her new novel, Refuge.

Listen to the interview (MP3) »“A page-turner of a novel, Refuge reminds us how the gift of sanctuary shapes both those who offer it and those who receive it.”

– Shyam Selvadouri, twice winner of the Lambda Literary Award, author of Cinnamon Gardens and The Hungry Ghosts

“This novel patiently accrues richness and layered resonance in the manner of a long life—in fact, like the almost century-long life of its stubborn, vital heroine. It also explores in personal and intimate terms the most important issues of our time: the nature of borders and belonging and the plight of the refugee.”

– Steven Heighton, author of the Governor General’s Award–winning The Waking Comes Late.

“A silk scarf of a novel, which catches on far-flung places and deep heartaches and gathers them into an old woman’s gnarled and feisty memory. Merilyn Simonds shows how mysterious we remain to ourselves and to each other after even a century of living.”

– Elizabeth Hay, author of Giller Prize–winning Late Nights on Air

“Revolving around a single unlikely hub—the restless and irascible Cass McCallum (whose motto might be: Living is hard, but Loving is harder)—this whirling journey through the 20th century is energized by fateful encounters with people, places, history and Nature, all of which invite us to reconsider with freshly invigorated senses the world we think we know, and the kinships we think we share, even with those we hold most dear.”

– John Vaillant, author of The Jaguar’s Children and winner of the Governor General’s Award, the BC Book Prize, and the Windham Campbell Literature Prize.

“This is truly Historical Fiction at its finest. Yes, there is romance, but written without the sappy icing. The story is fascinating, and reaches deep into the spirit of family, heritage, and community.”

–Etain

“a beautifully crafted literary novel, both historic and contemporary — a masterpiece of a work — and also a deeply compelling mystery, a novel that will haunt me for some time to come.”

–Sandra

“Rare is the novel I must read, from beginning to end, in one sitting. Merilyn Simonds’s Refuge is one of those few gems.”

–Laurie Mackie

“The tapestry of a life is what Refuge holds. From Cassandra’s first musing, I was drawn into her narrative. It is beautiful. It is heart wrenching. It is representative of a woman’s strength and desire to both persevere and disappear. Thank you Net Galley for allowing me to be one of the first to hear what it means to both seek and offer Refuge.”

–Amy

“I can’t tell you how many times in the last two or three years that I have started reading a book only to put it aside, unfinished. Refuge held my interest from the first page until the last. I cared about the characters, found them all to be interesting people living in interesting times. Cassandra MacCallum is unforgettable.”

–David Sweet, bookseller

Books & Company, Picton, ON

“…bracing and beautiful.”

– Sarah Murdoch, Toronto Star

“an integrated tableau of dramatic snapshots of a century in which one woman’s unusual life interconnects with war, culture, scientific discovery, the plight of the refugee and the fragility of love.”

– Jamie Portman, The Windsor Star

“Refuge is bejewelled by fine writing. In terms of structure and imagery, it is a marvel. Names of insects, insect lore, some science, some history, diseases, weird musical instruments, musicians, artists, photographers, costumes, and a treasure that ruins everything as treasure is wont to do—the novel is itself a treasure trove, presided over by the grand dame who tells lies right to the very end.”

– Debra Martens, Canadian Writers Abroad

“Cass’s need to confront her past honestly and Nang’s search for refuge coalesce in a tense and emotionally wrought narrative.”

– Nancy Powell, Shelf Awareness

“You don’t make it to ninety-six without accumulating a few stories, and Cassandra MacCallum is no different, although she didn’t expect, at that age, to learn something new about her past. Merilyn Simonds moves back and forth between present in past, gently revealing all of the things that made Cassandra who she is: kind of cantankerous, definitely skeptical, but also, undeniably curious about what she might have missed.”

– Alexandra Donaldson, Edit Seven

“Simonds is one of those (few) writers who can pull off both fiction and fact. Elizabeth Hay (herself no slouch was a writer) called Refuge “a silk scraf of a novel,” It is far more than that. [I’m] placing Refuge onto my “keep forever” shelf of fine Canadian fiction.”

– Andrew Armitage, Owen Sound Sun-Times

“Simonds paints a portrait of two intriguing women who have more in common than is at first obvious. Without being overly sentimental, it’s a moving and deeply satisfying tale.”

– New York Journal of Books

“Is Merilyn Simonds’s Refuge a fictional memoir, a historical novel, or an exploration of the causes and results of seeking refuge? It’s all three, as it turns out, and a mystery besides.”

– Foreword Reviews

“Do you believe what you see with your eyes or what you see with your heart? That question, raised by Simond’s layered and nuanced account of an extraordinary life, will provoke thought in skeptics and believers alike.”

– Kirkus Reviews

“Against the backdrop of almost a century of Canadian, Mexican, and American history, Simonds explores the sometimes unknown, astonishing, and enduring-against-all-odds connections between siblings, parents, and children that span generations—and the globe.”

–Booklist (US)

“Refuge interweaves Cass MacCallum’s painful reckoning with her family history and her developing relationship with Nang Aung Myaing. Simonds depicts the varied settings and incidents with adept and vivid specificity, but it’s Cass herself—sharp, determined, cantankerous—who provides unity to the narration. Cass must ultimately consider whether human connections, whatever their pretext, are more meaningful than blood ties…a moving conclusion to her fitful and often unhappy story.”

–Rohan Maitzen, Quill & Quire, July/August issue